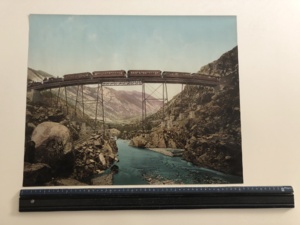

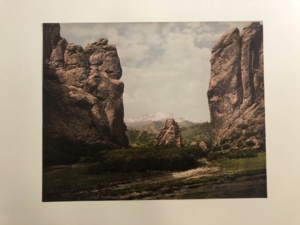

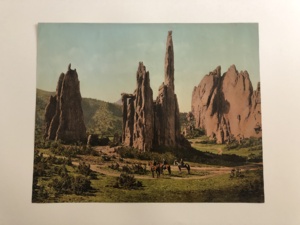

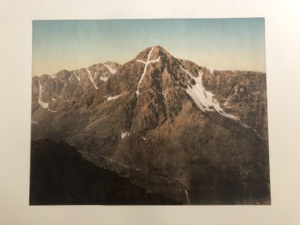

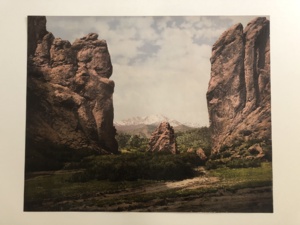

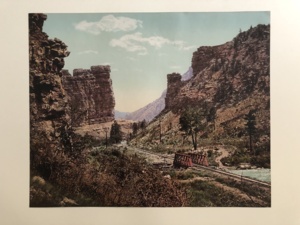

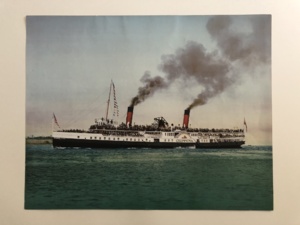

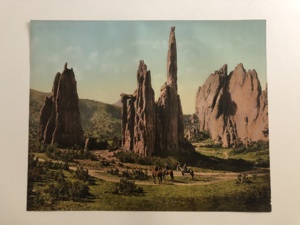

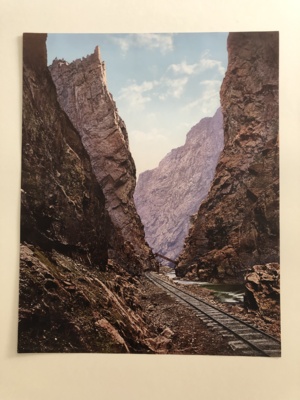

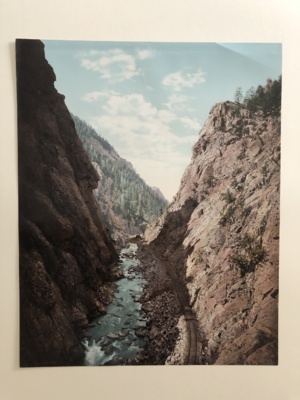

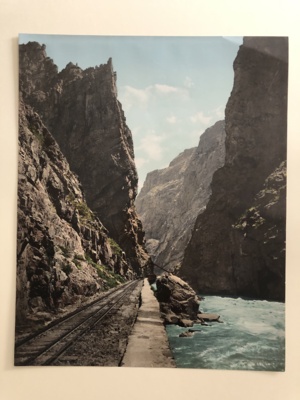

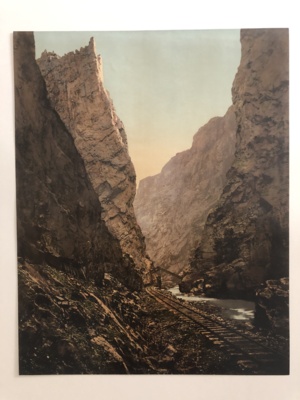

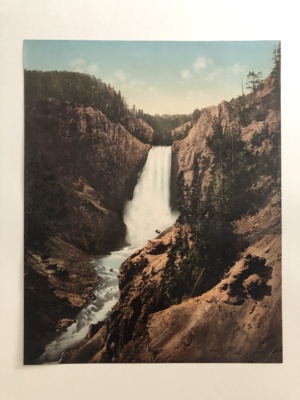

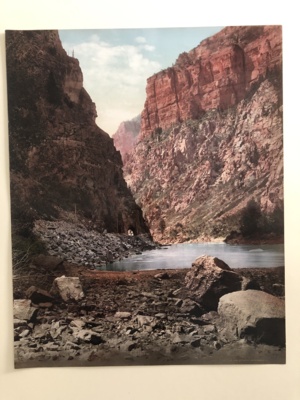

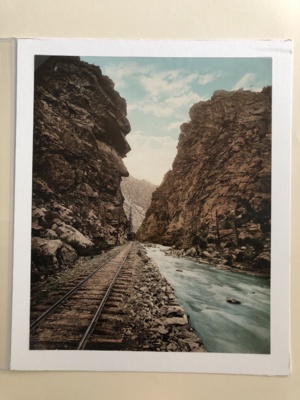

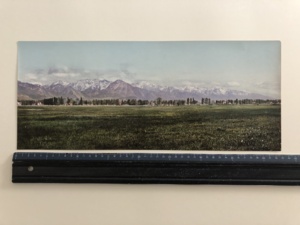

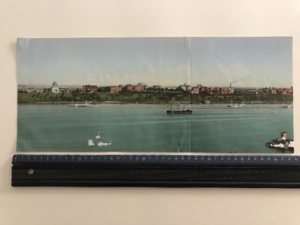

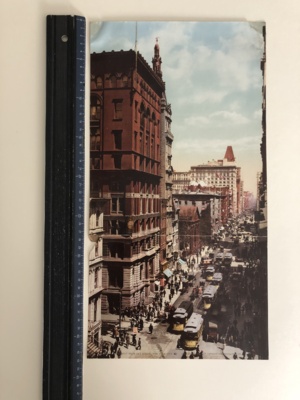

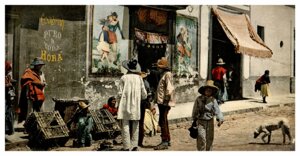

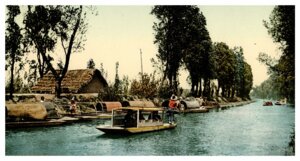

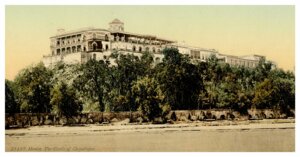

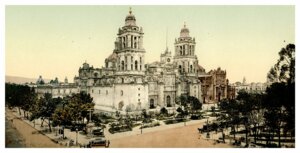

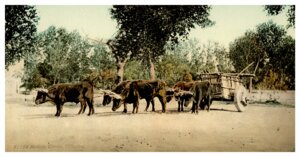

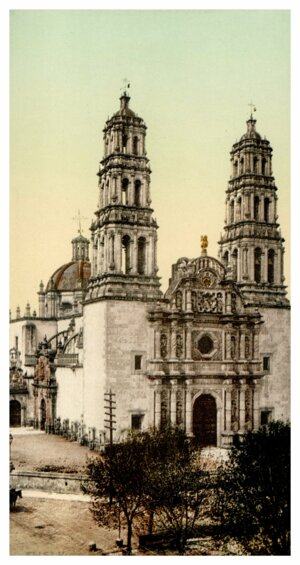

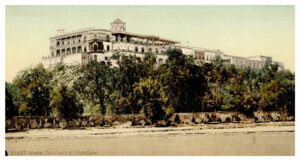

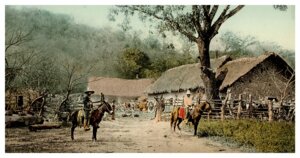

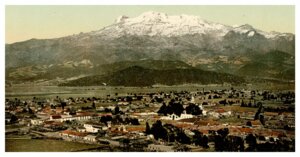

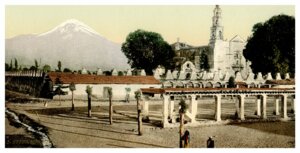

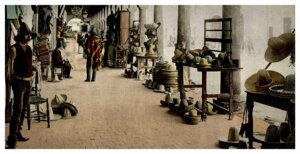

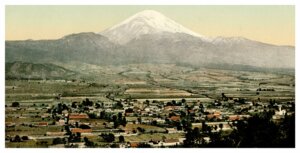

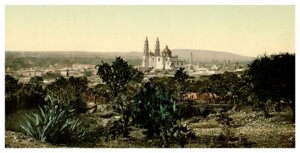

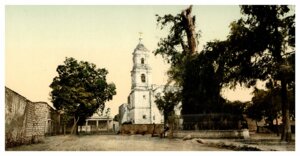

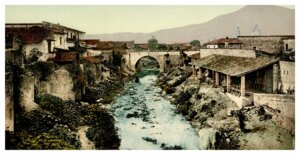

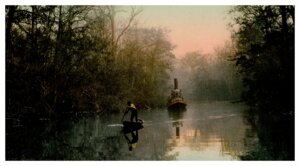

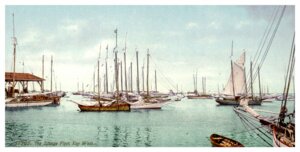

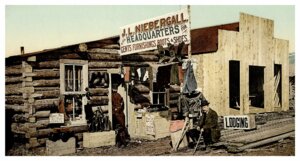

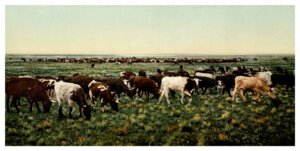

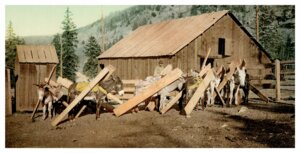

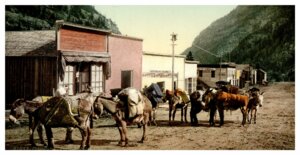

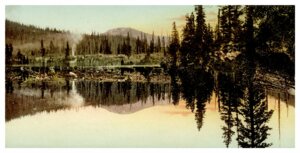

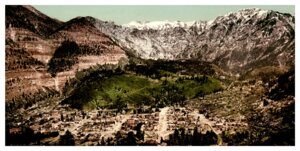

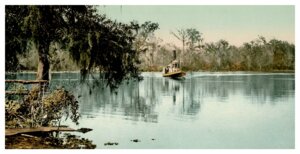

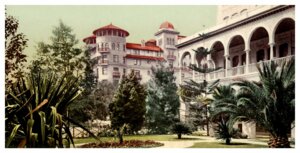

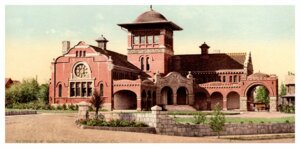

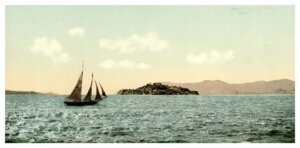

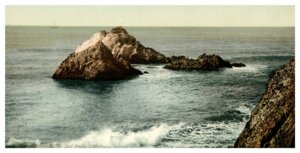

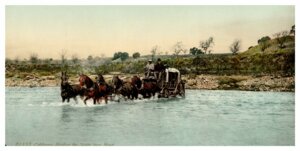

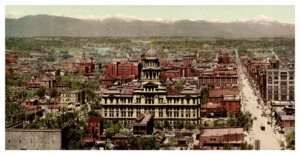

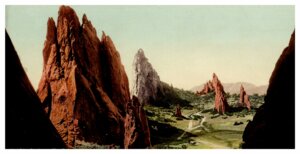

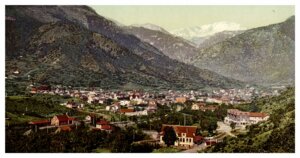

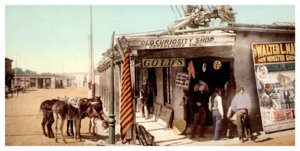

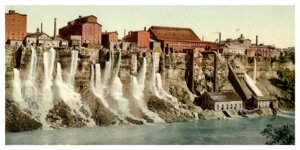

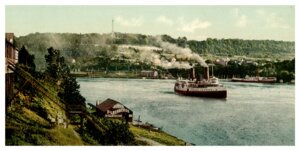

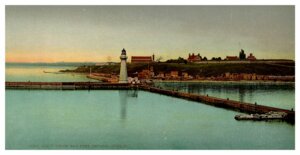

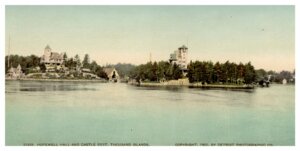

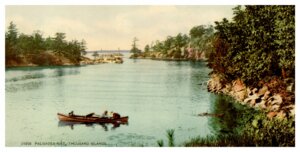

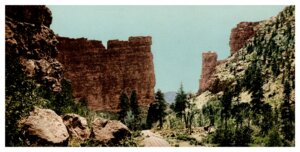

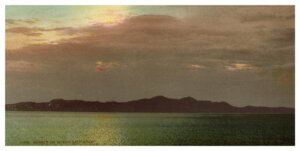

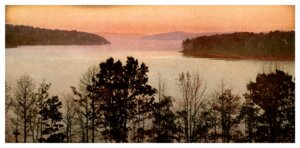

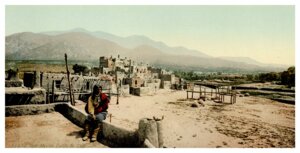

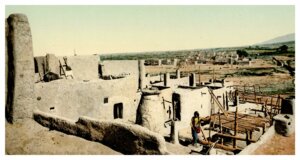

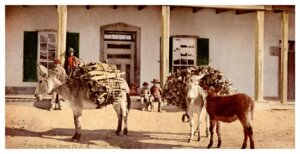

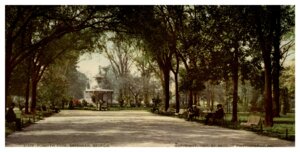

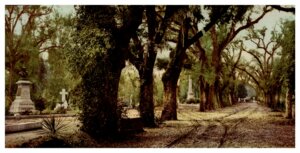

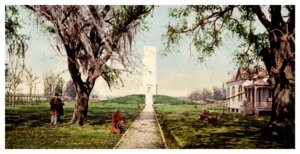

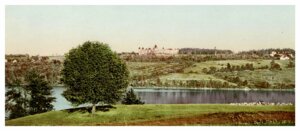

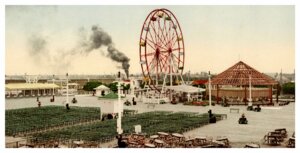

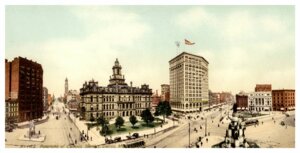

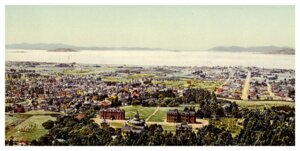

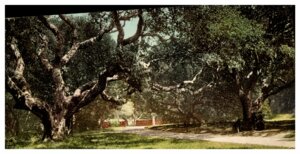

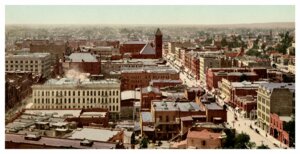

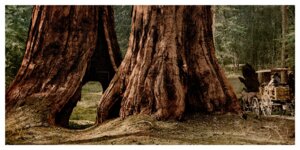

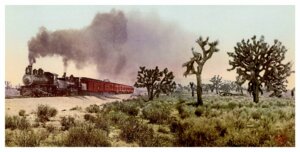

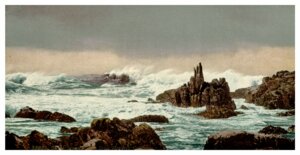

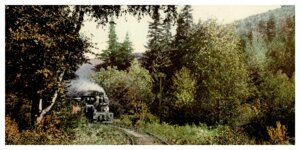

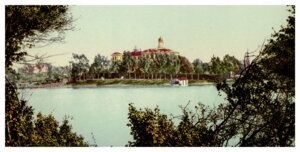

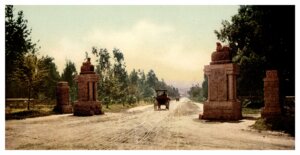

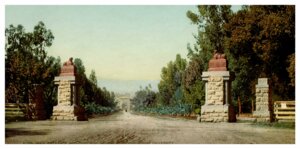

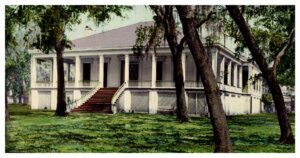

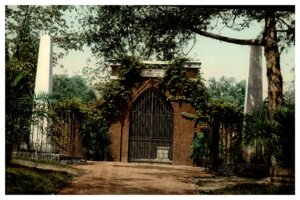

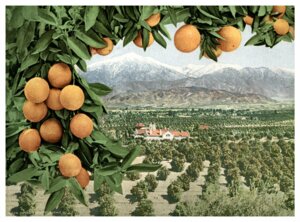

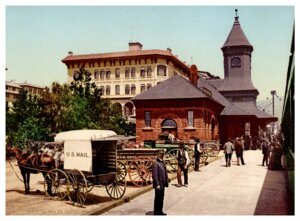

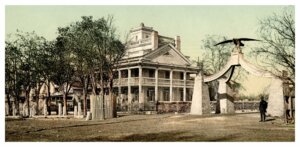

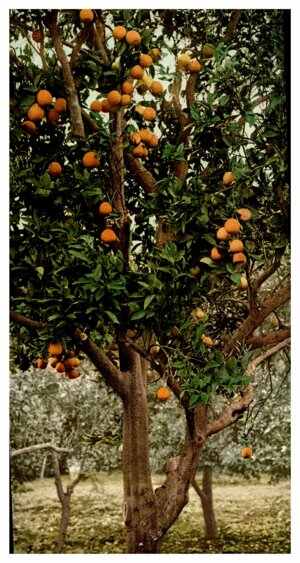

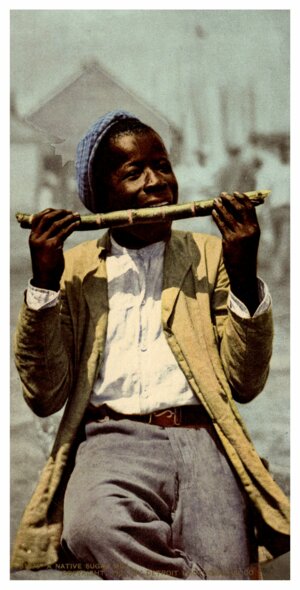

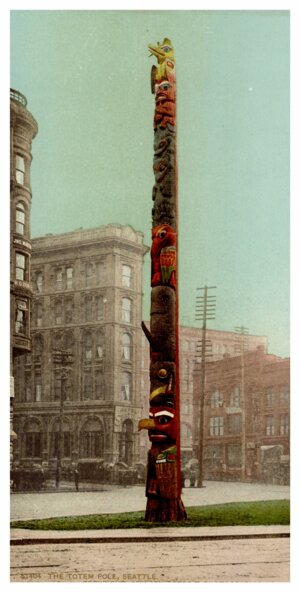

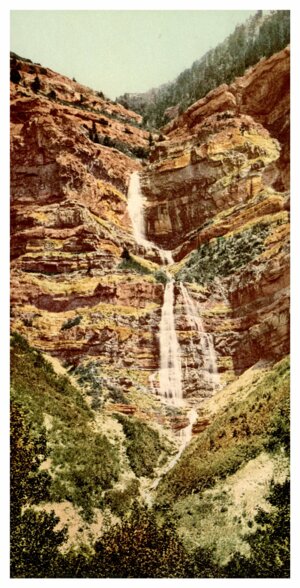

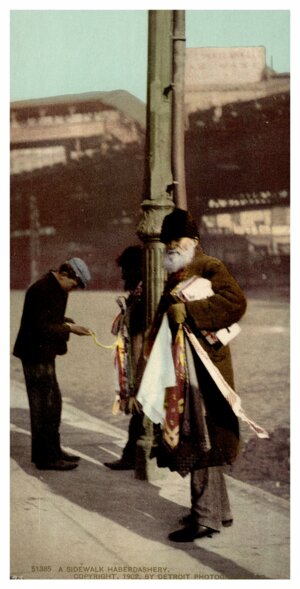

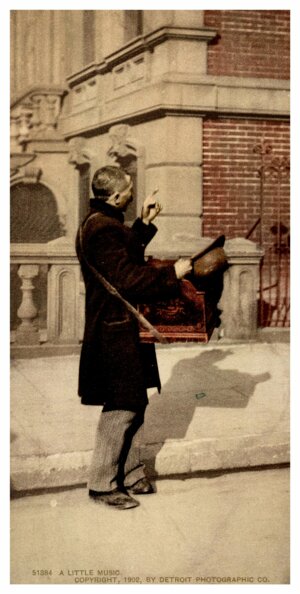

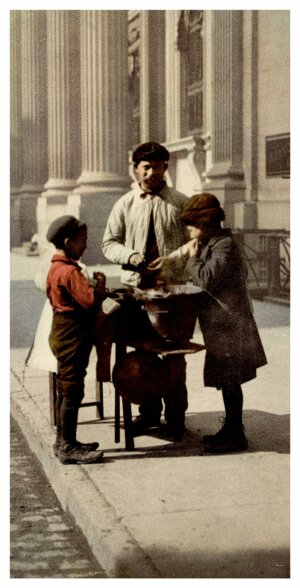

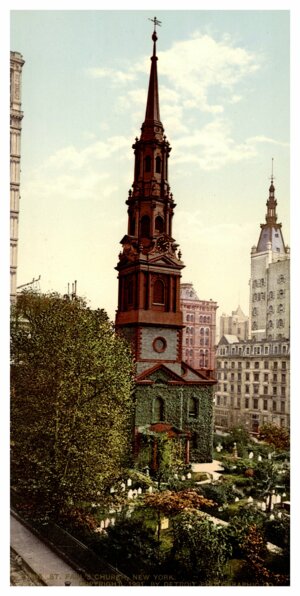

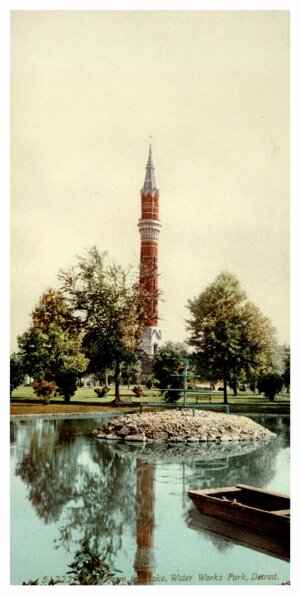

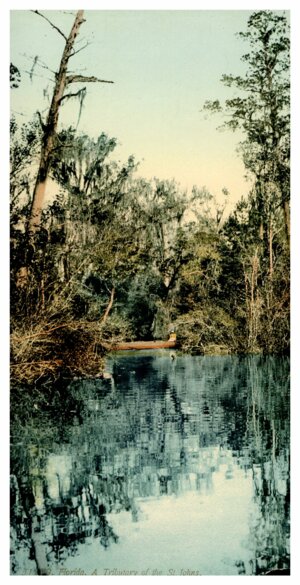

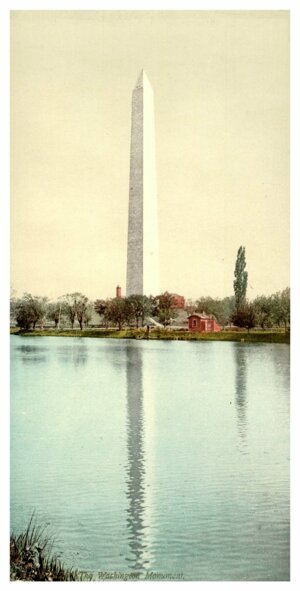

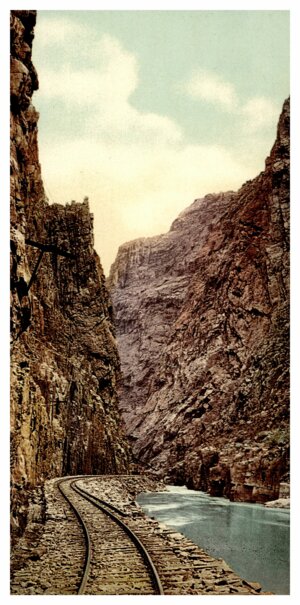

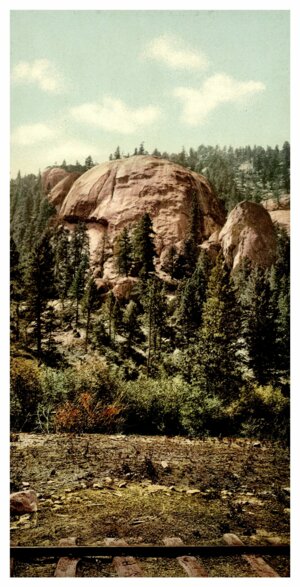

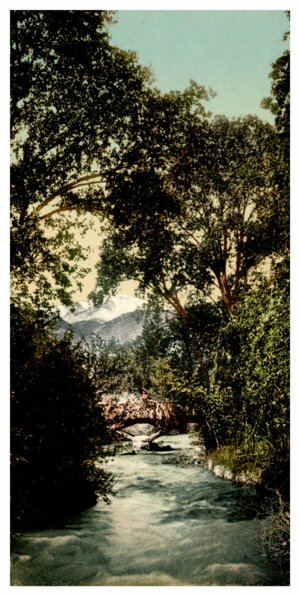

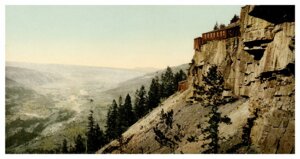

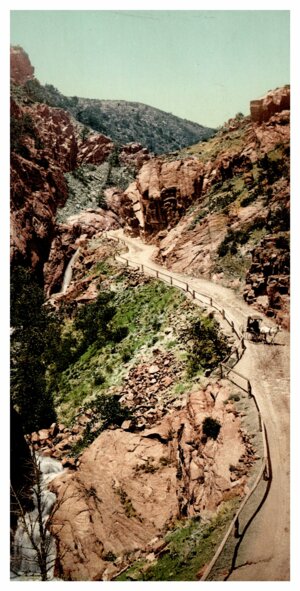

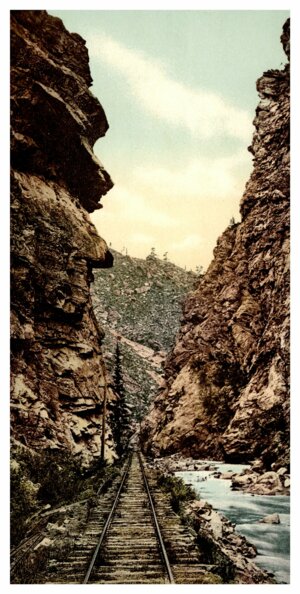

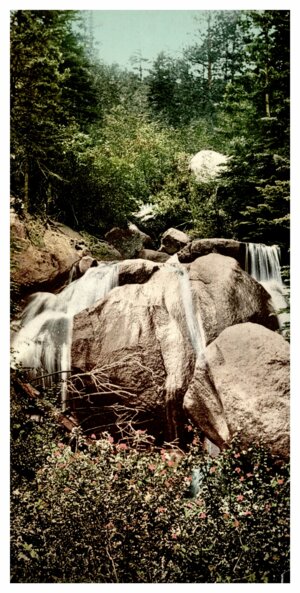

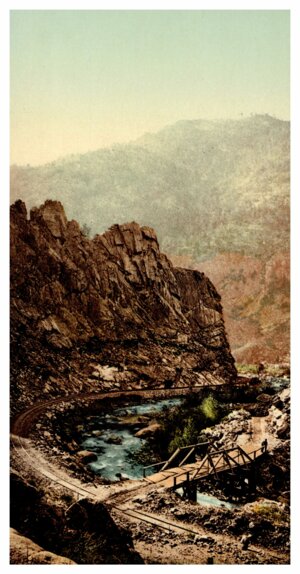

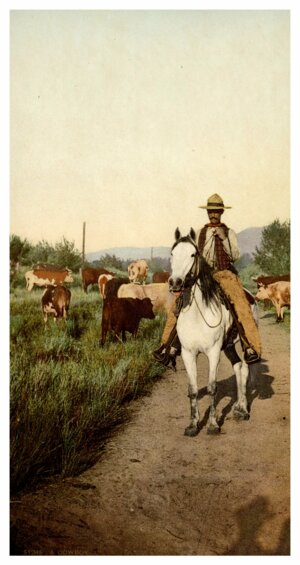

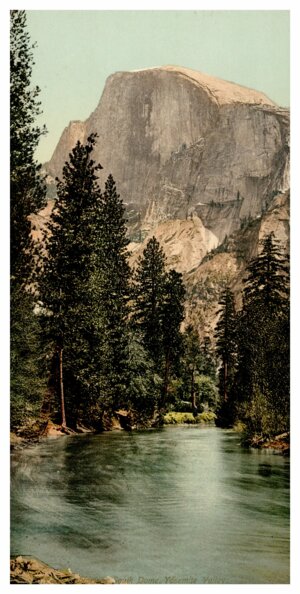

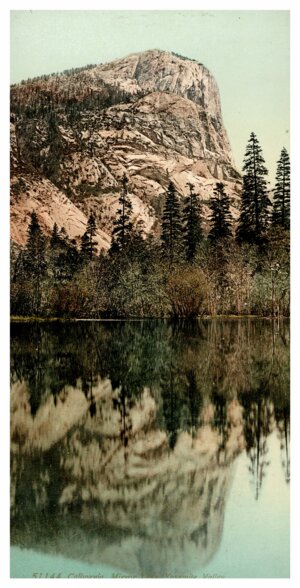

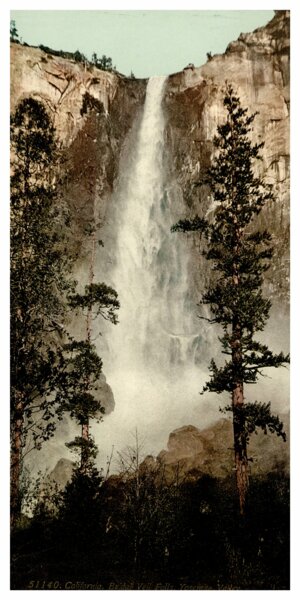

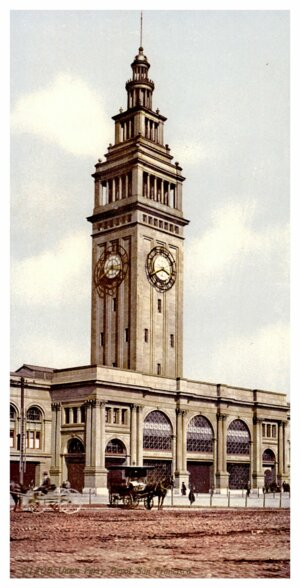

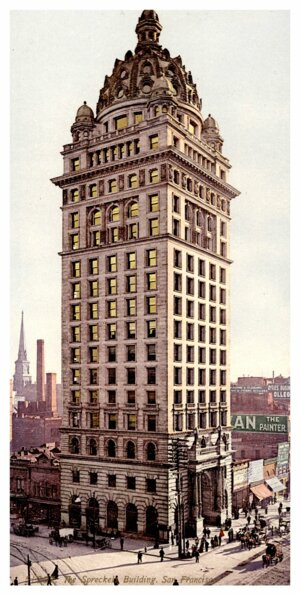

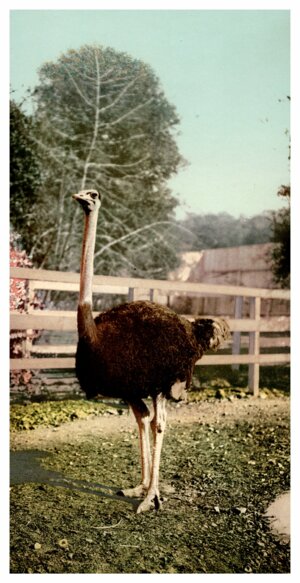

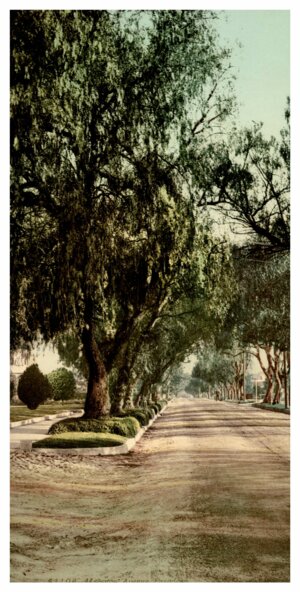

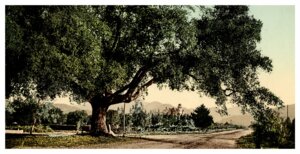

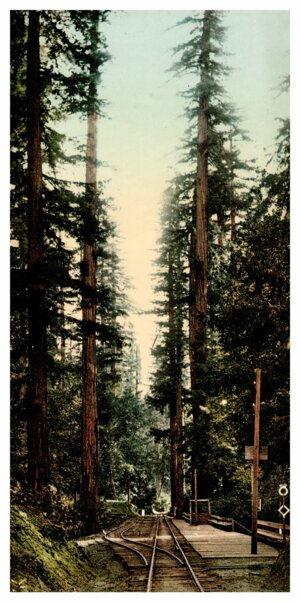

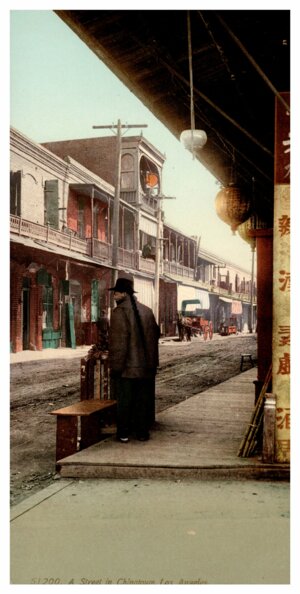

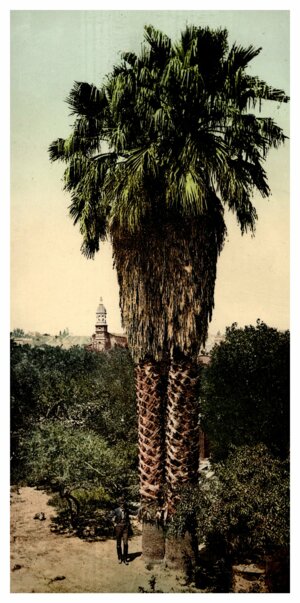

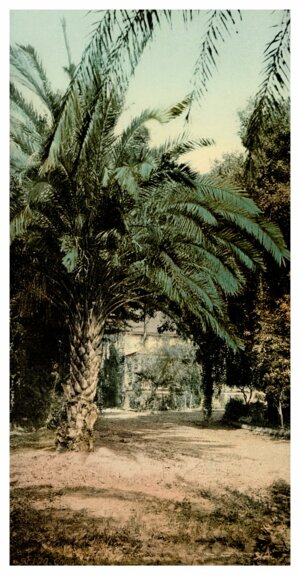

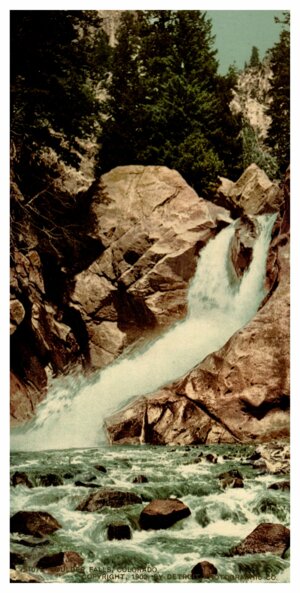

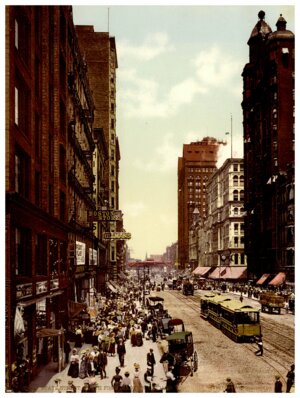

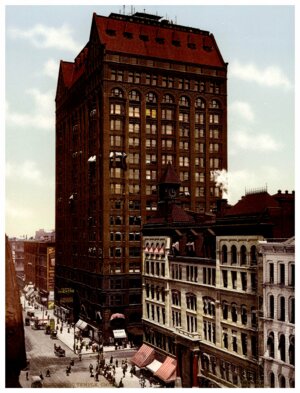

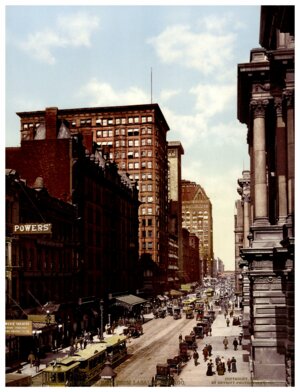

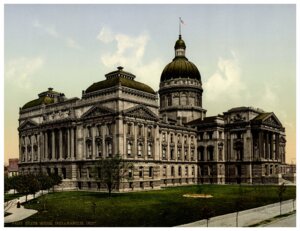

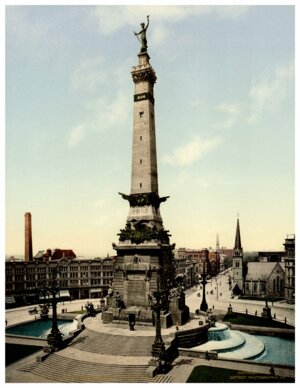

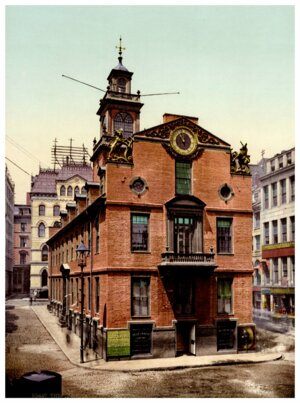

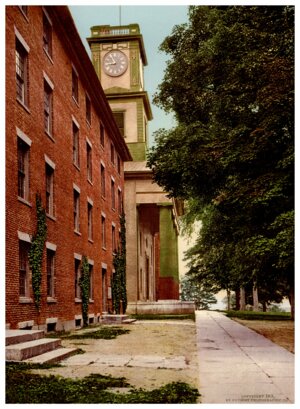

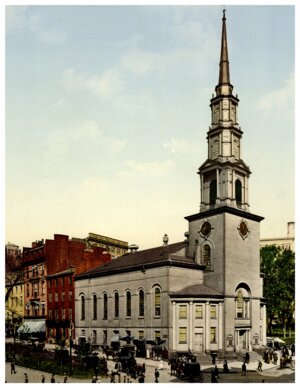

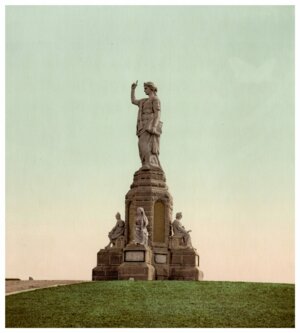

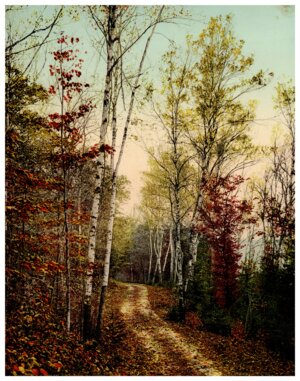

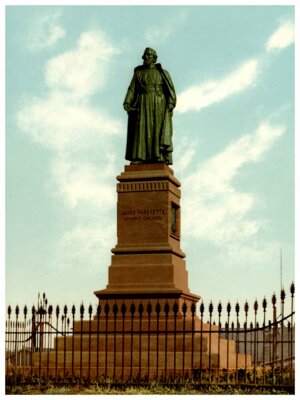

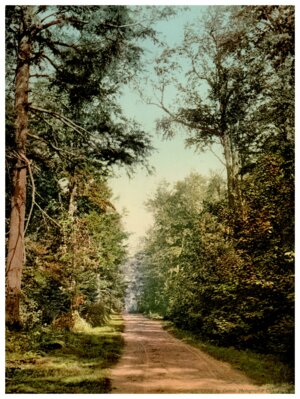

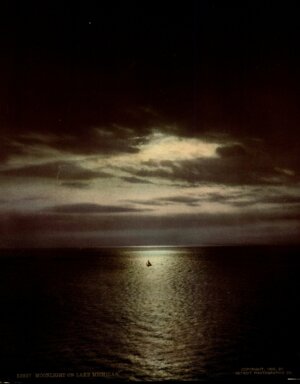

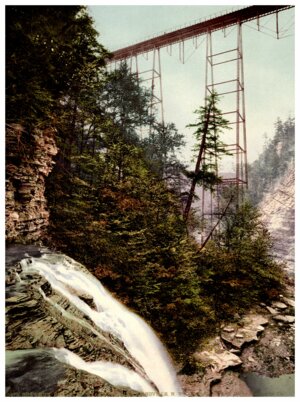

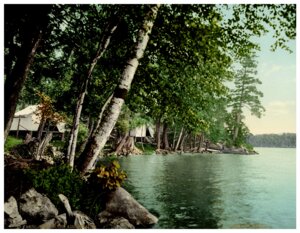

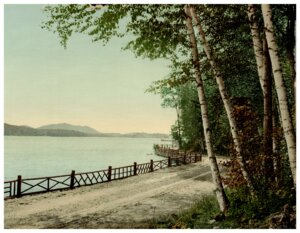

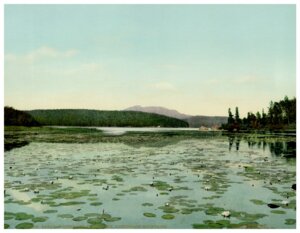

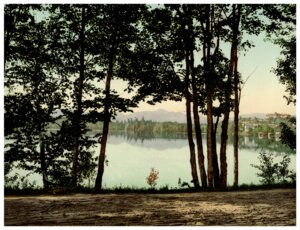

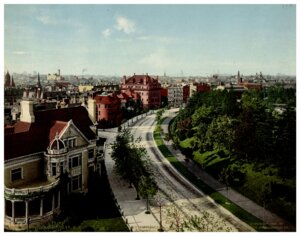

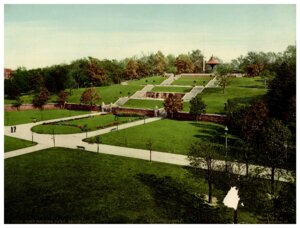

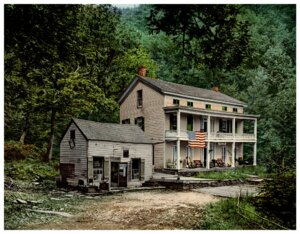

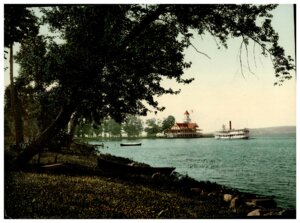

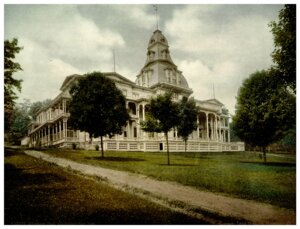

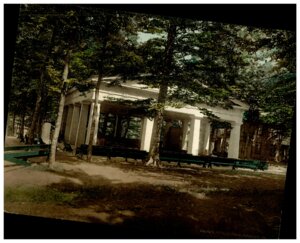

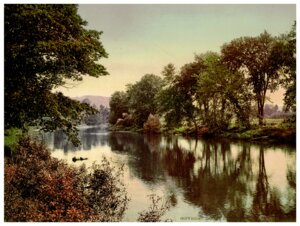

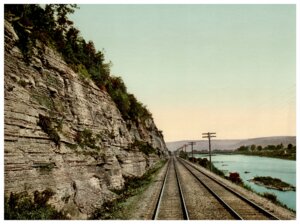

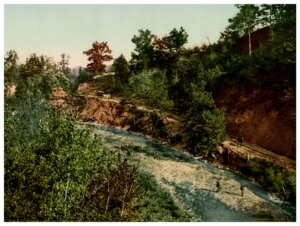

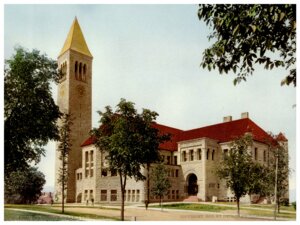

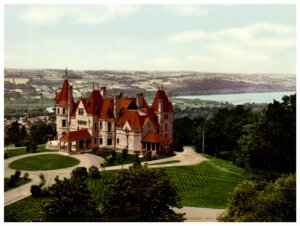

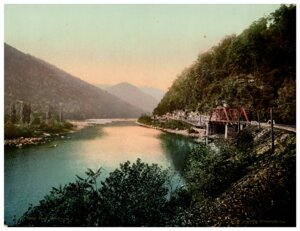

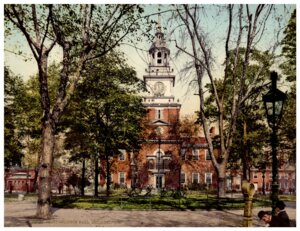

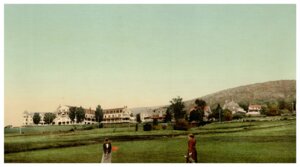

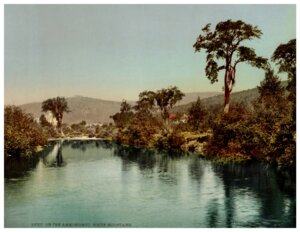

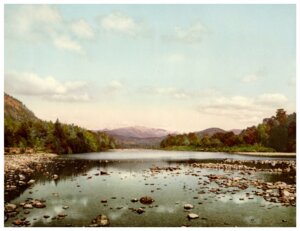

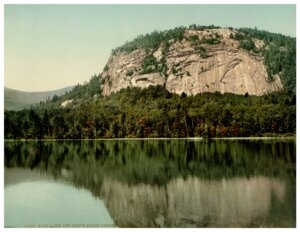

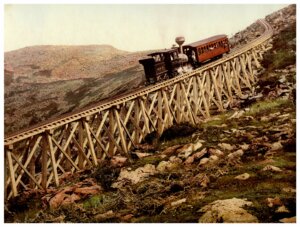

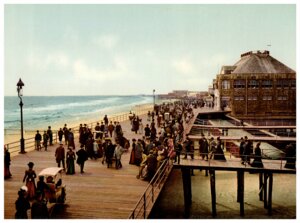

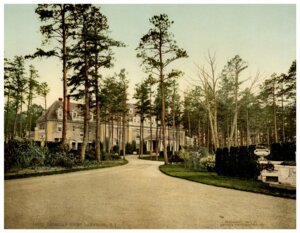

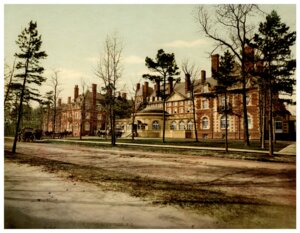

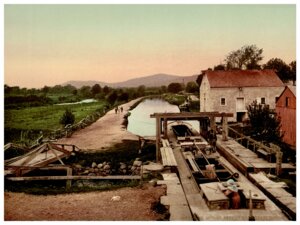

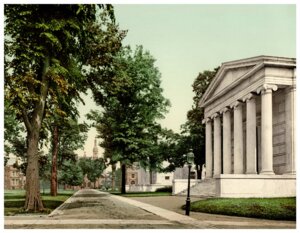

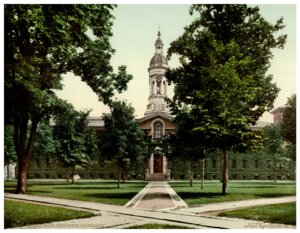

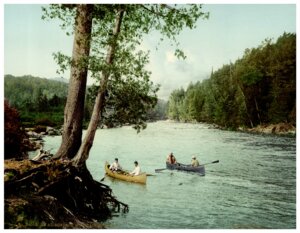

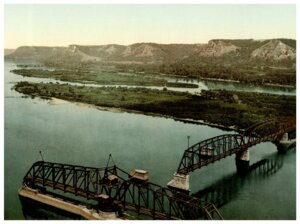

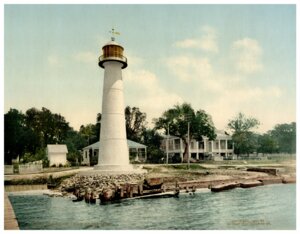

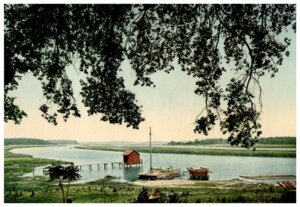

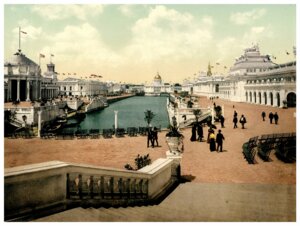

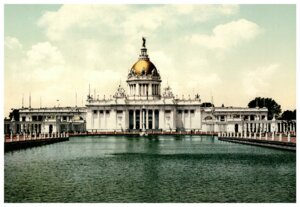

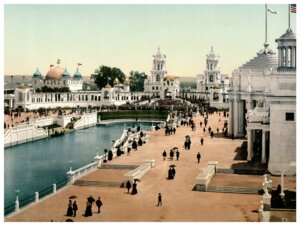

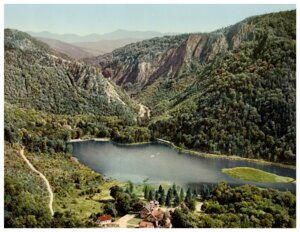

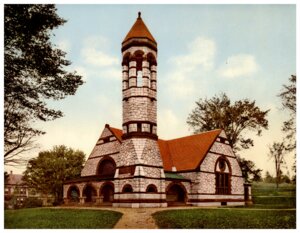

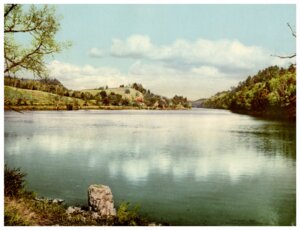

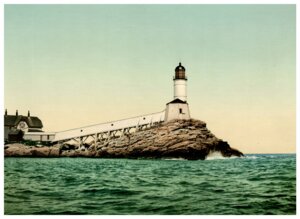

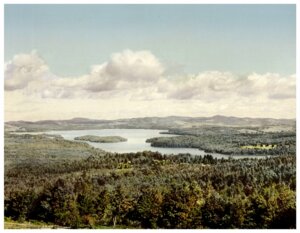

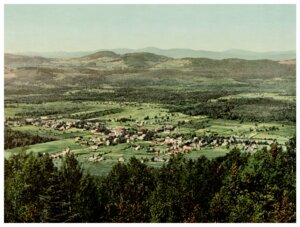

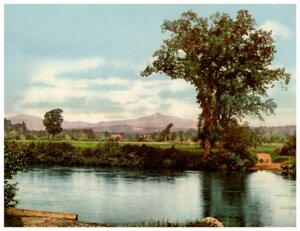

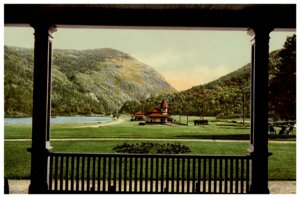

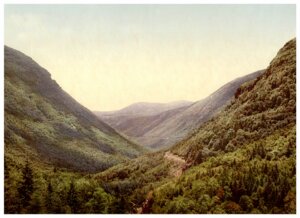

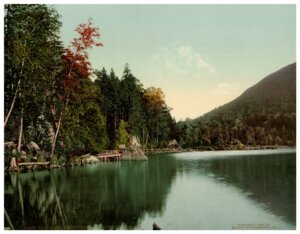

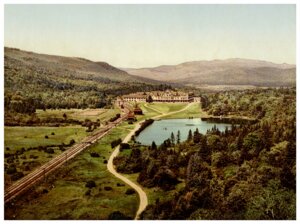

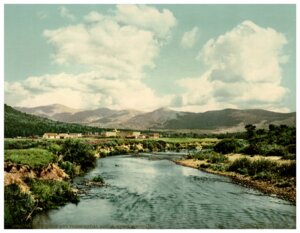

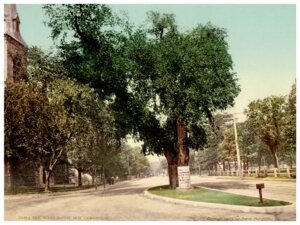

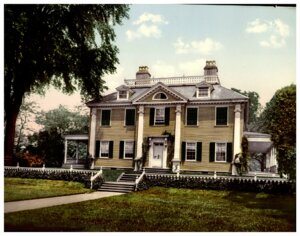

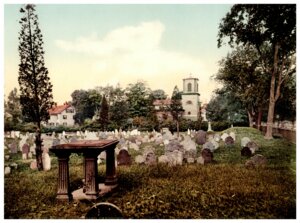

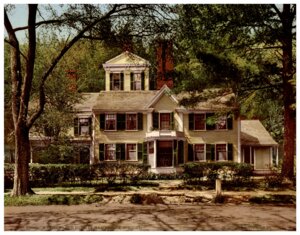

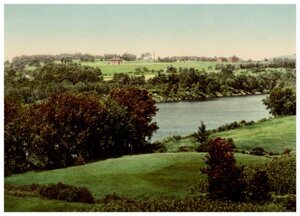

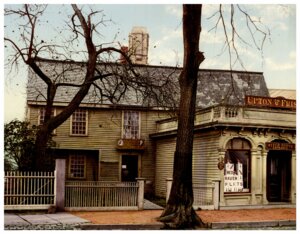

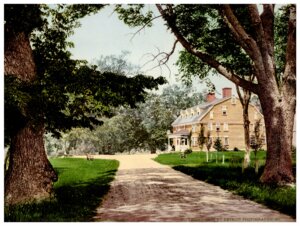

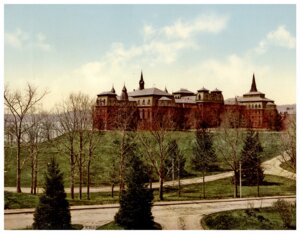

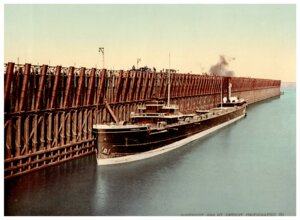

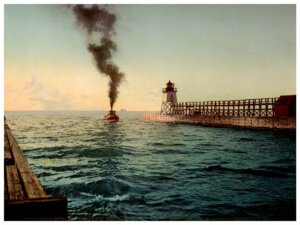

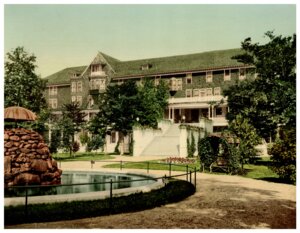

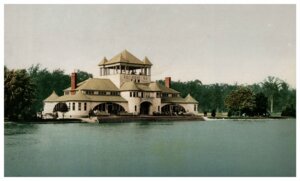

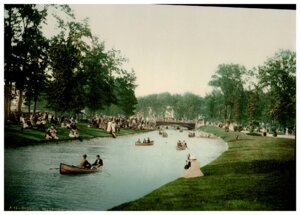

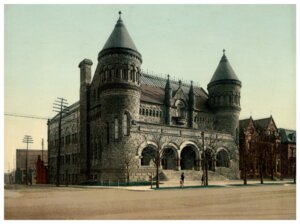

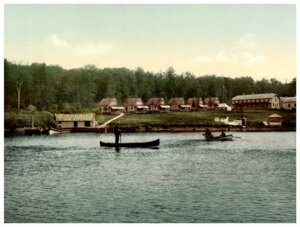

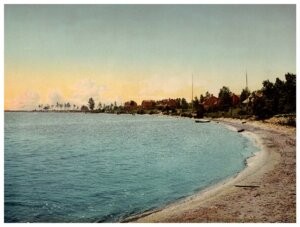

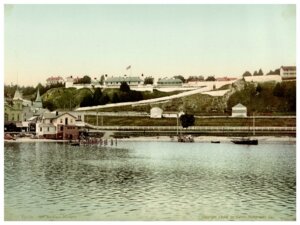

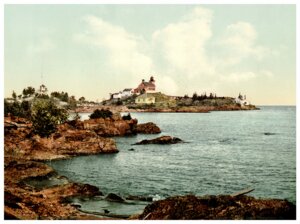

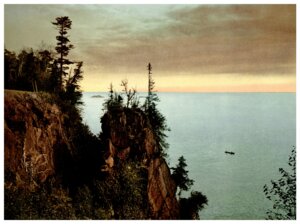

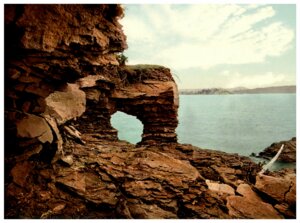

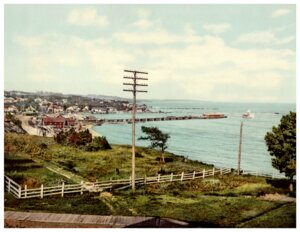

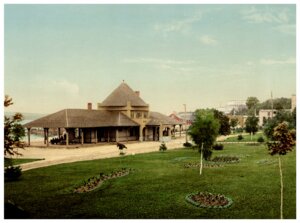

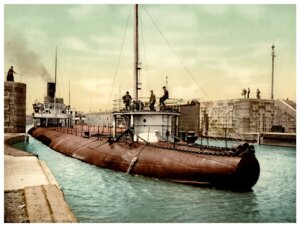

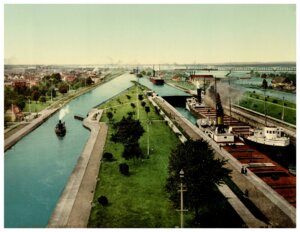

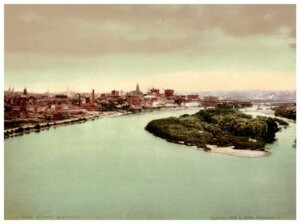

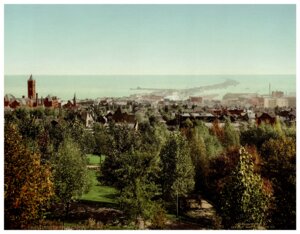

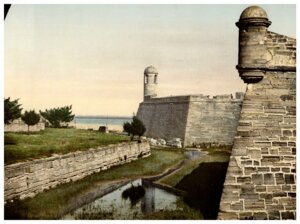

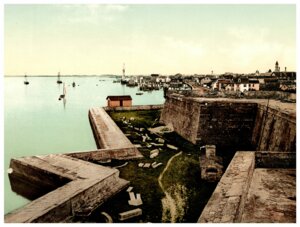

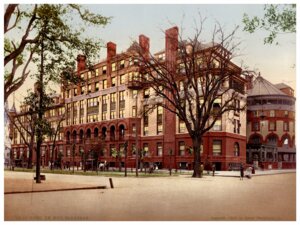

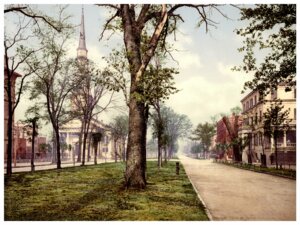

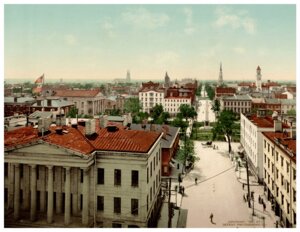

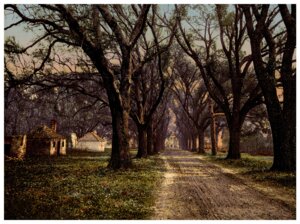

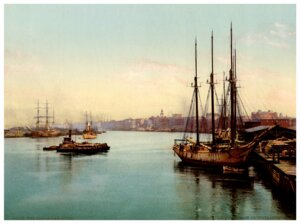

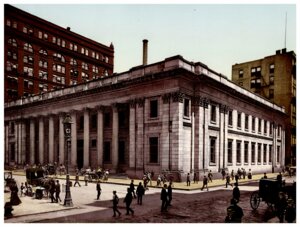

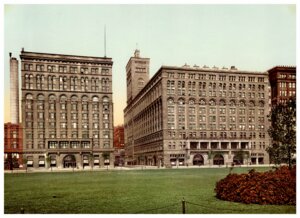

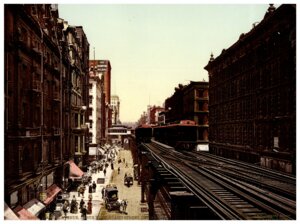

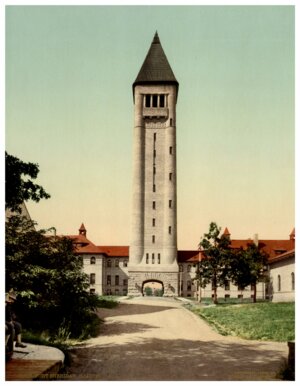

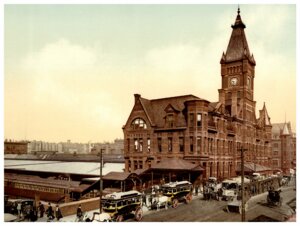

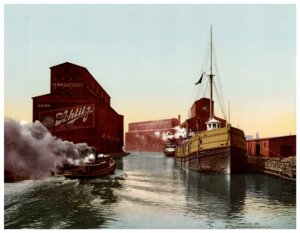

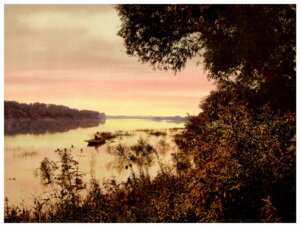

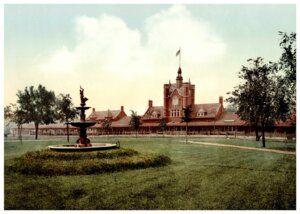

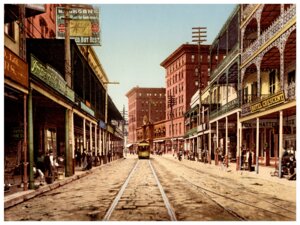

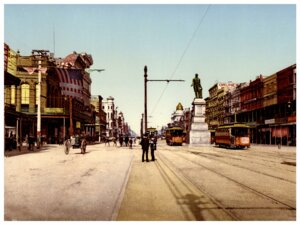

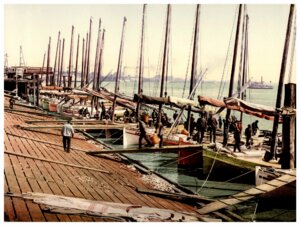

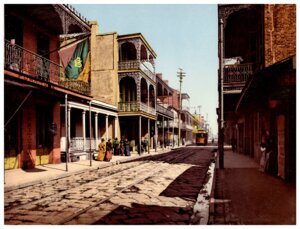

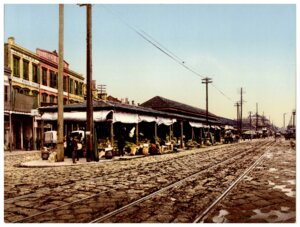

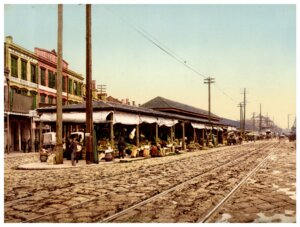

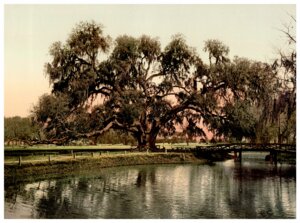

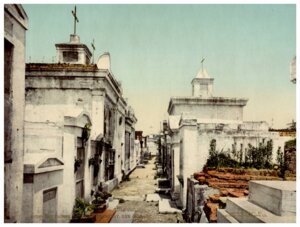

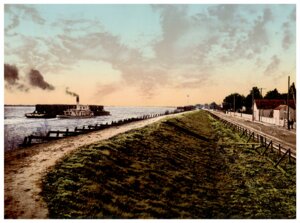

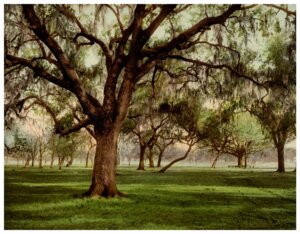

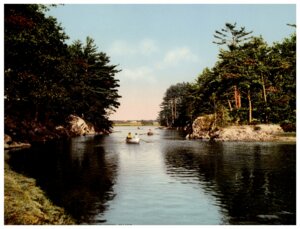

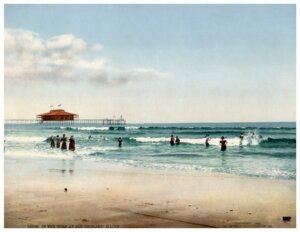

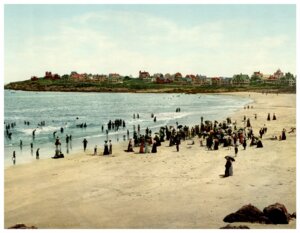

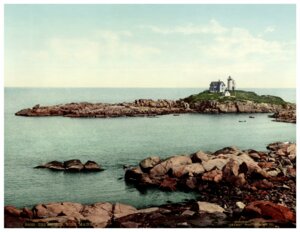

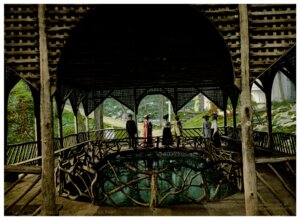

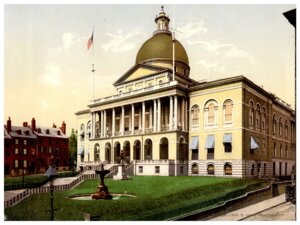

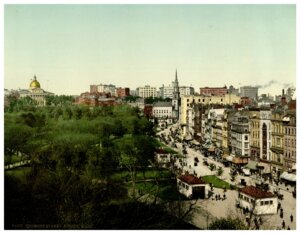

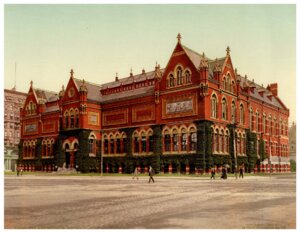

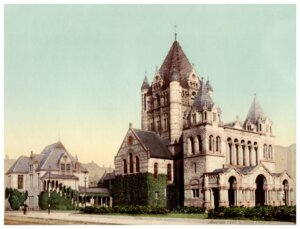

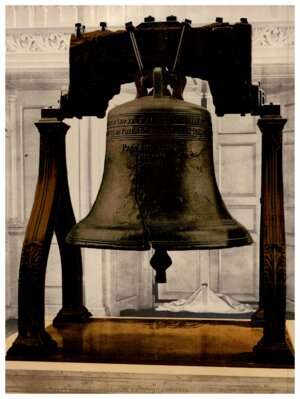

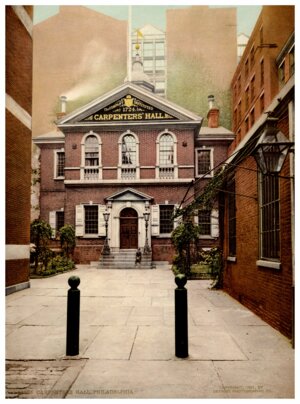

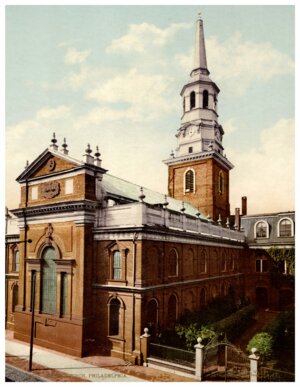

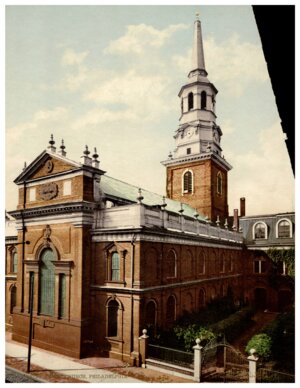

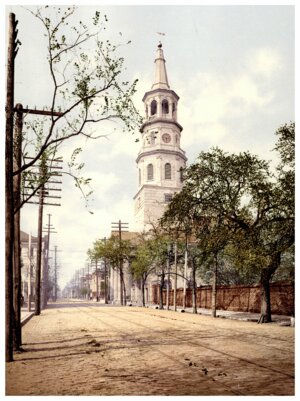

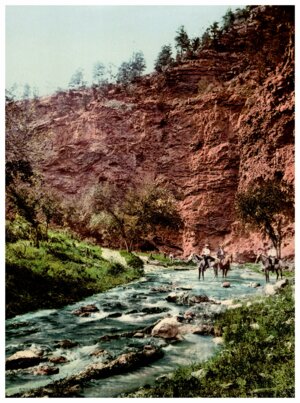

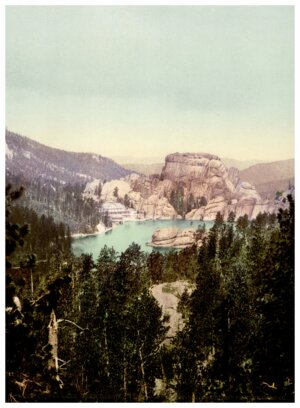

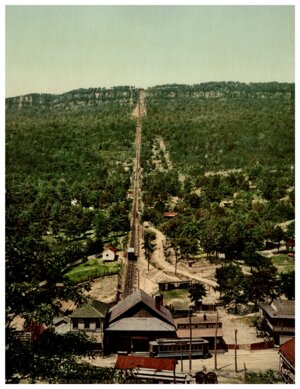

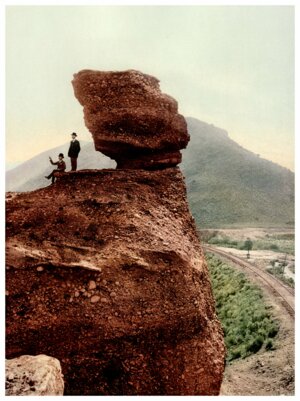

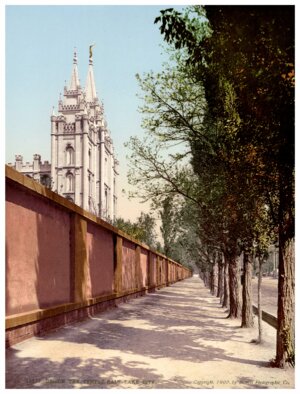

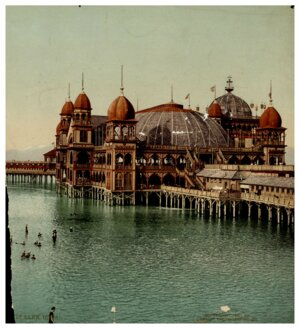

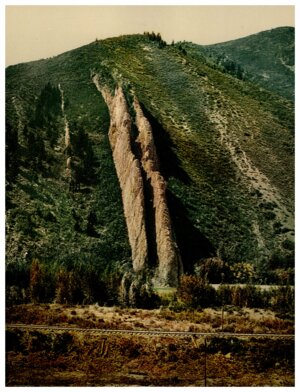

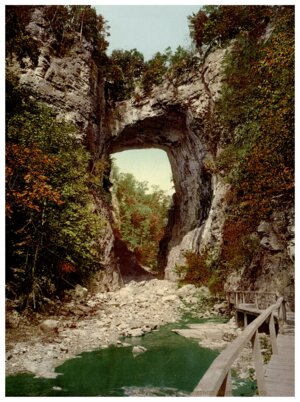

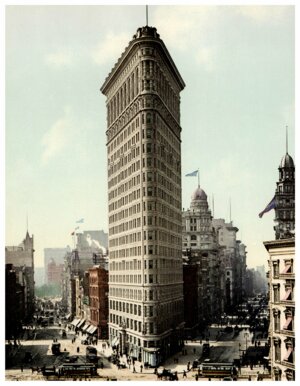

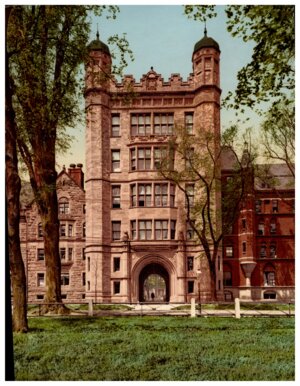

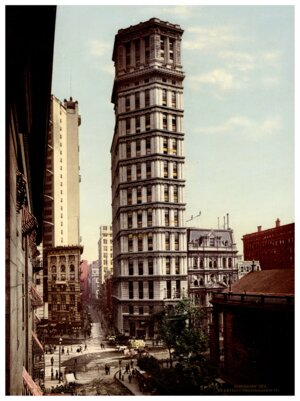

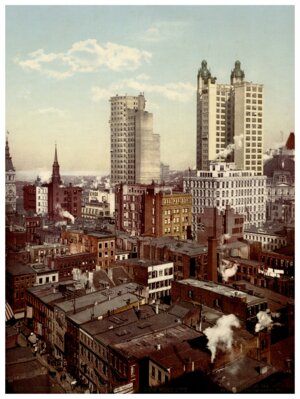

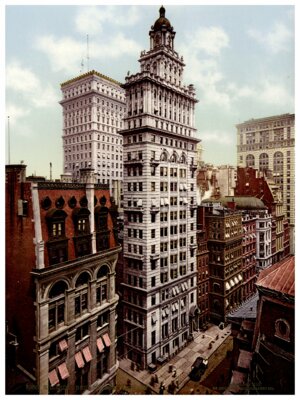

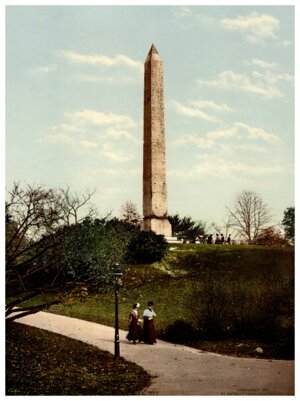

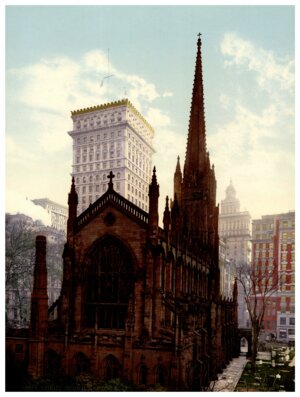

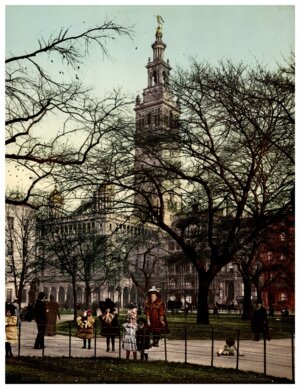

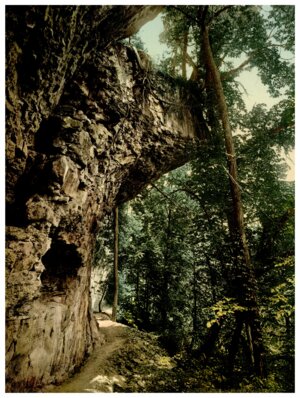

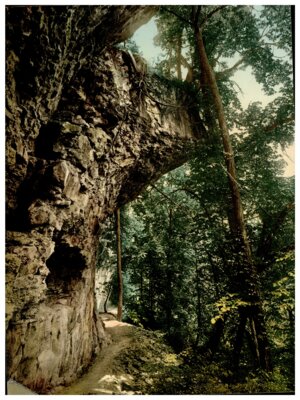

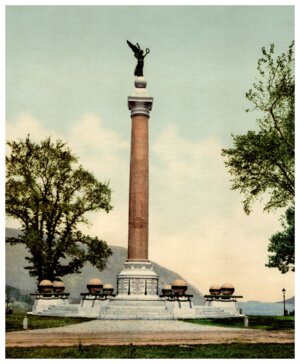

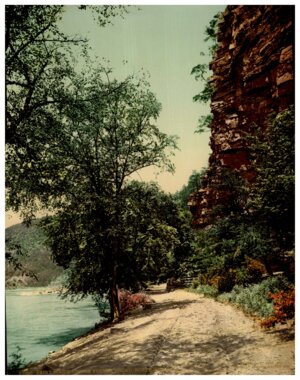

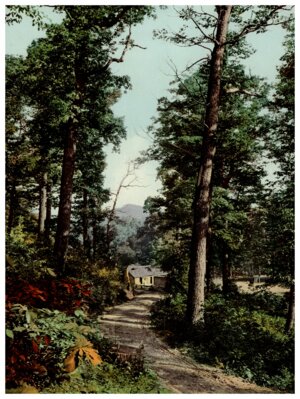

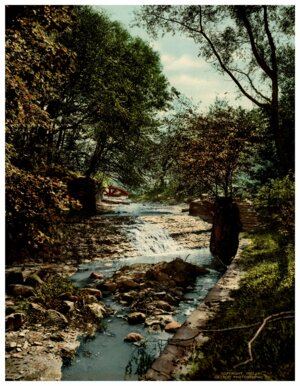

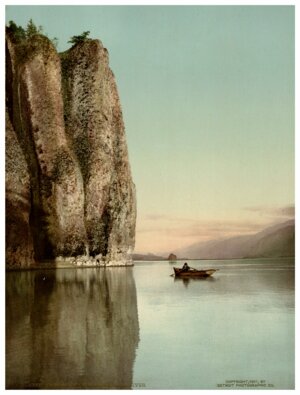

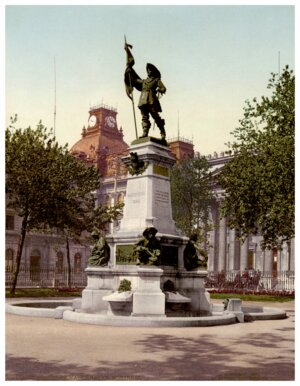

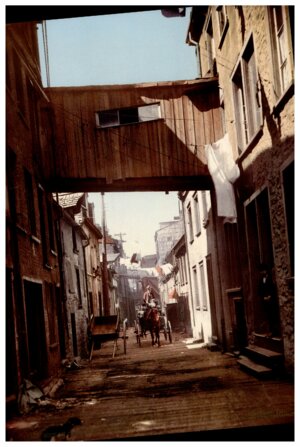

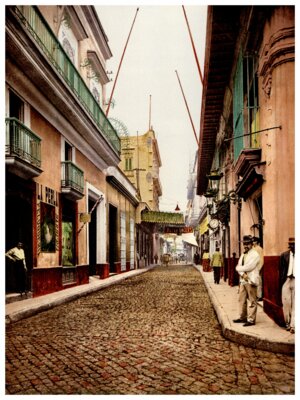

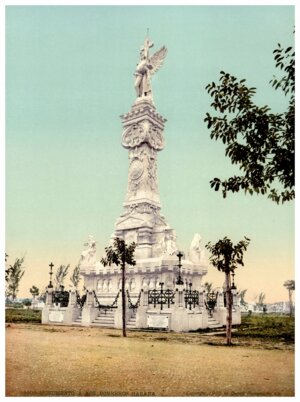

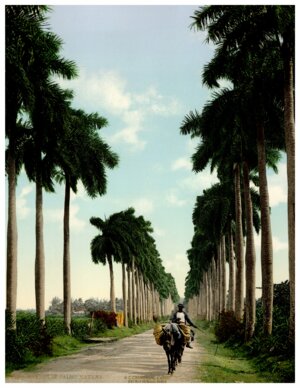

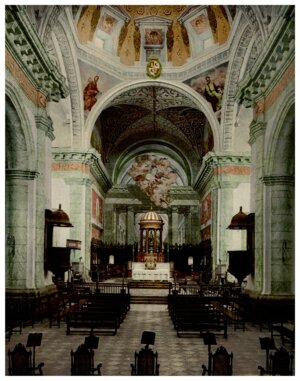

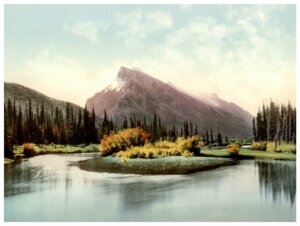

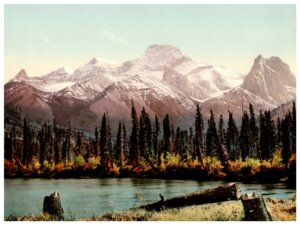

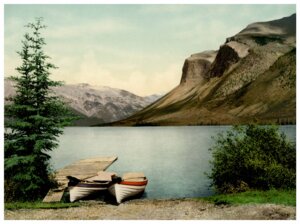

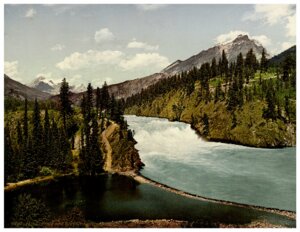

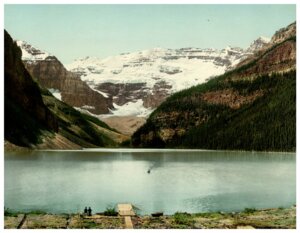

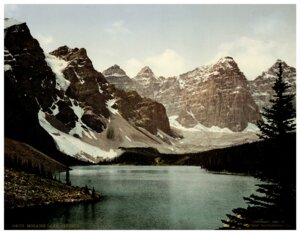

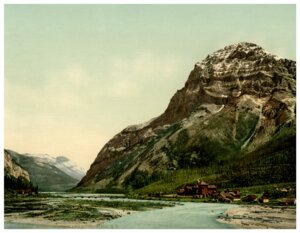

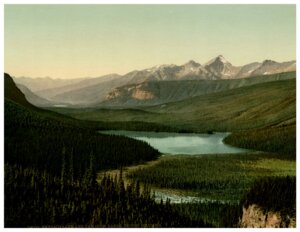

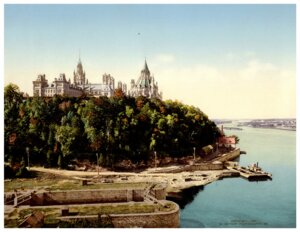

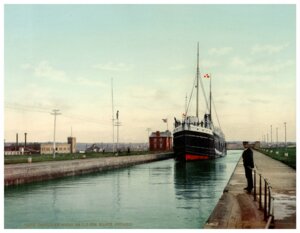

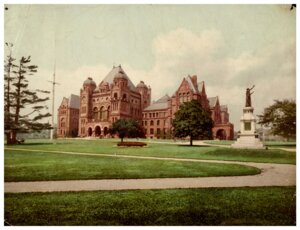

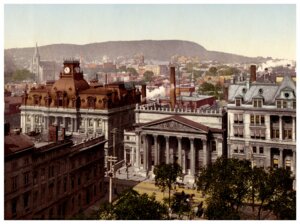

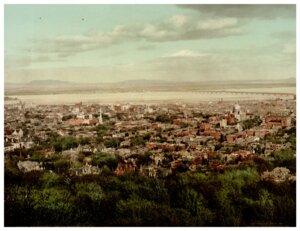

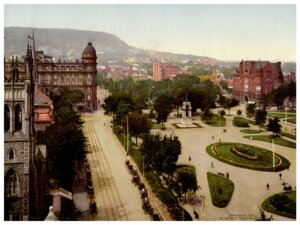

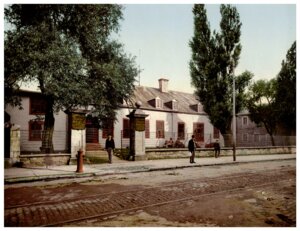

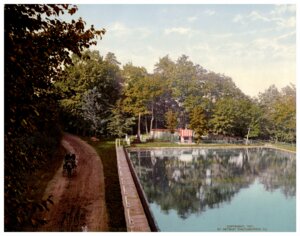

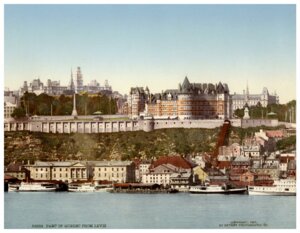

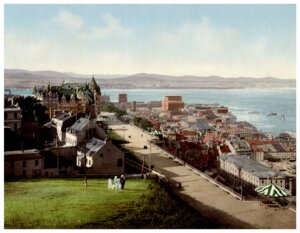

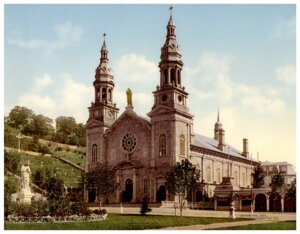

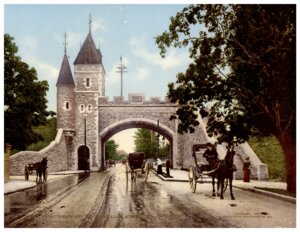

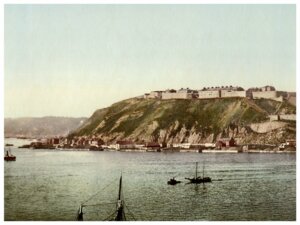

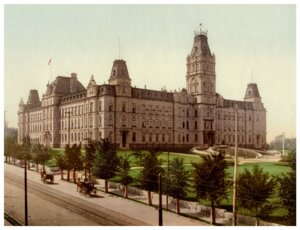

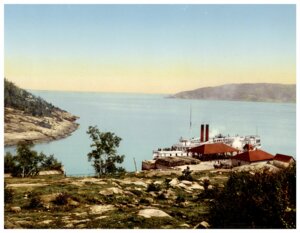

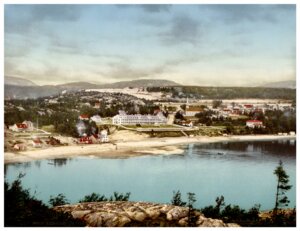

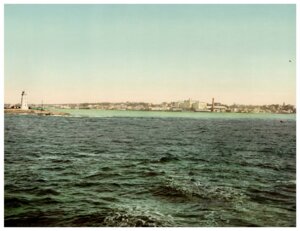

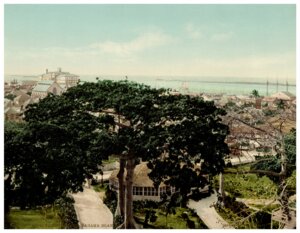

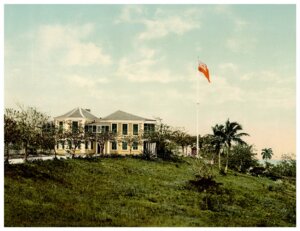

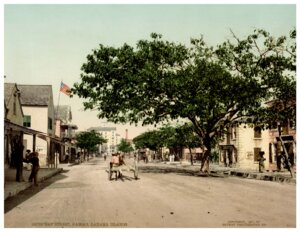

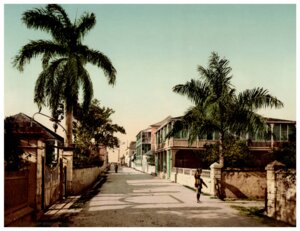

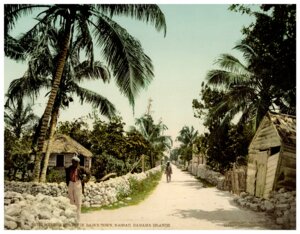

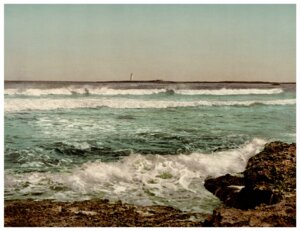

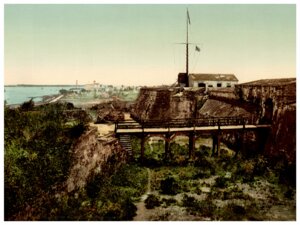

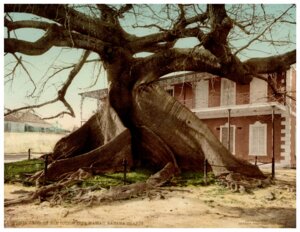

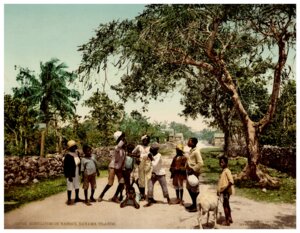

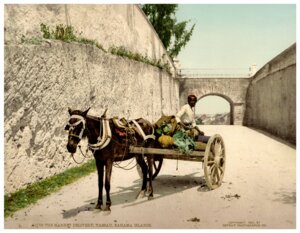

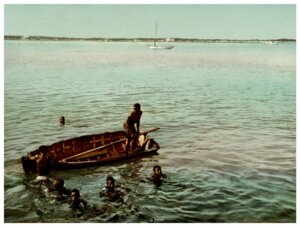

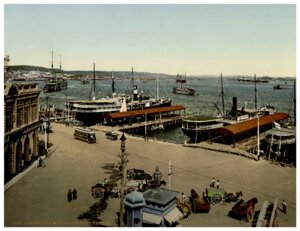

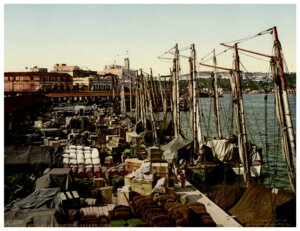

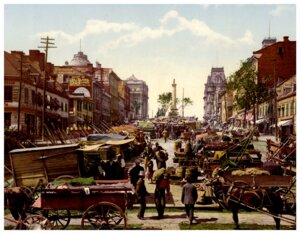

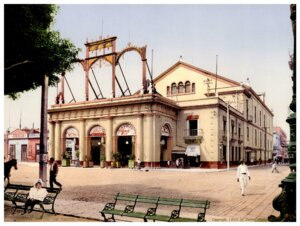

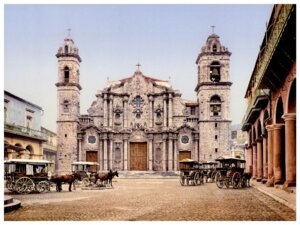

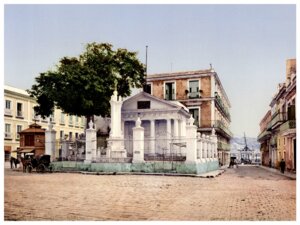

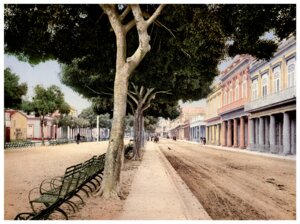

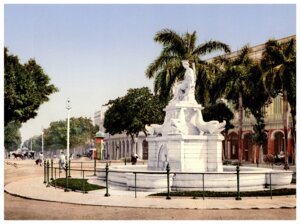

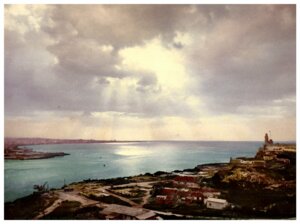

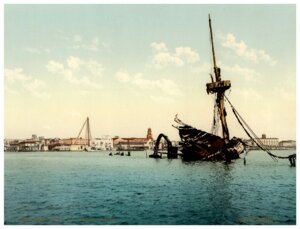

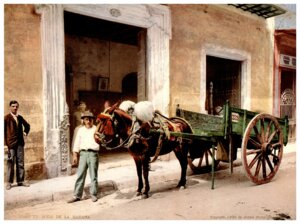

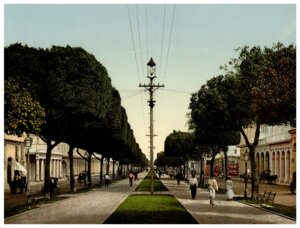

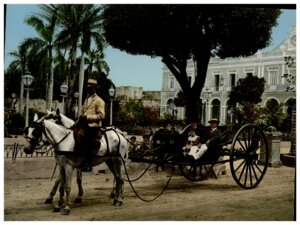

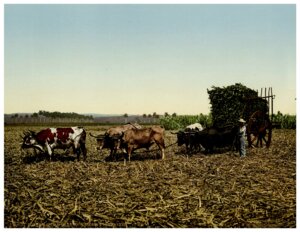

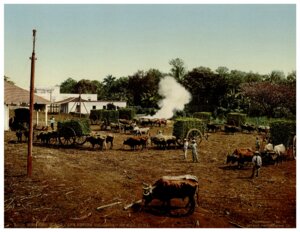

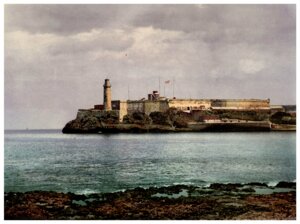

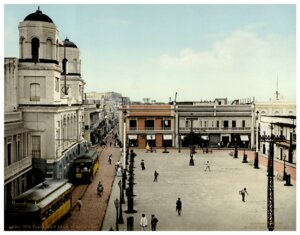

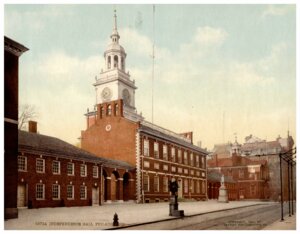

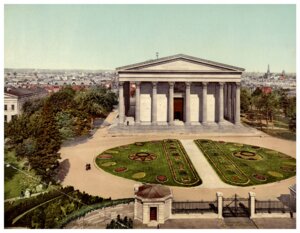

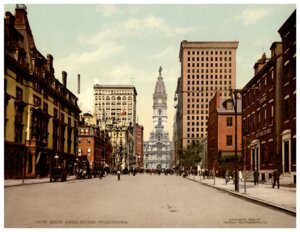

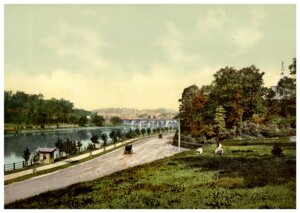

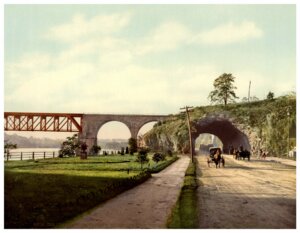

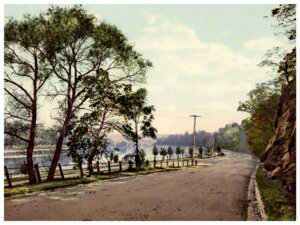

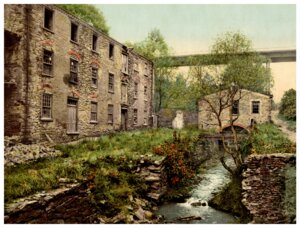

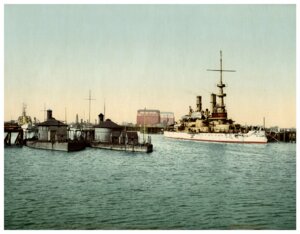

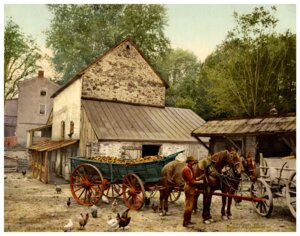

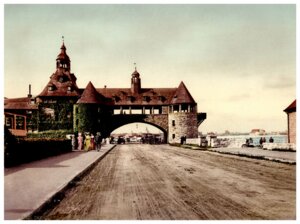

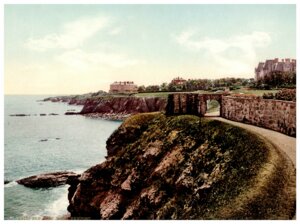

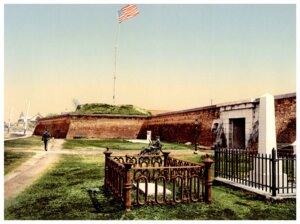

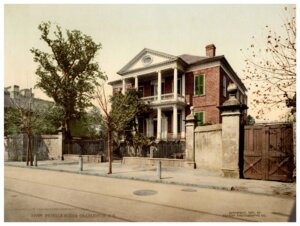

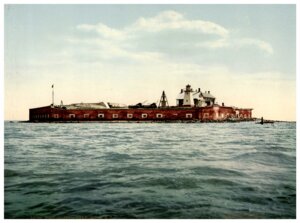

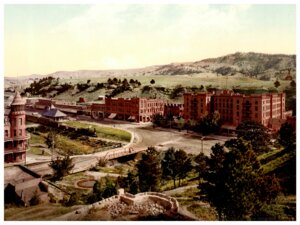

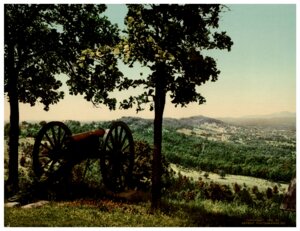

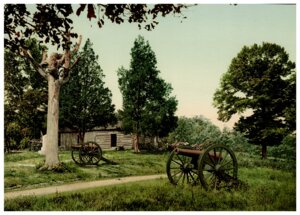

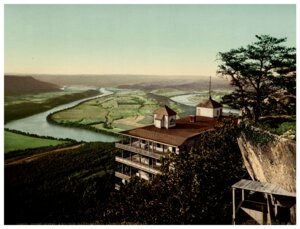

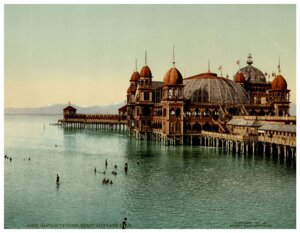

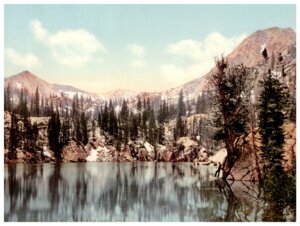

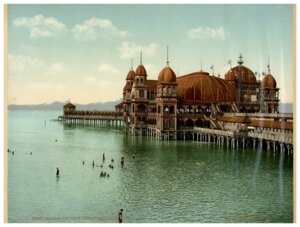

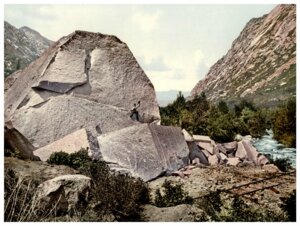

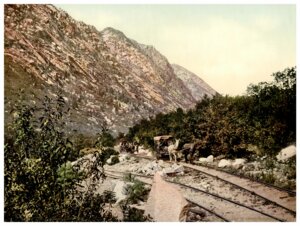

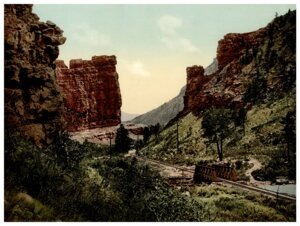

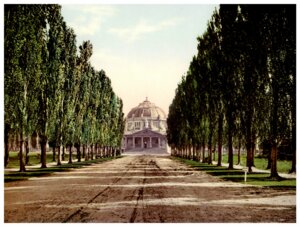

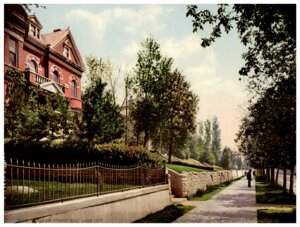

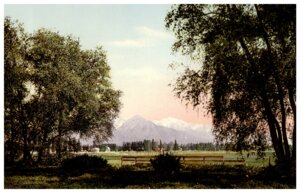

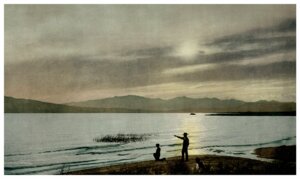

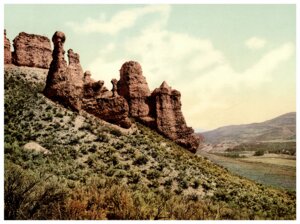

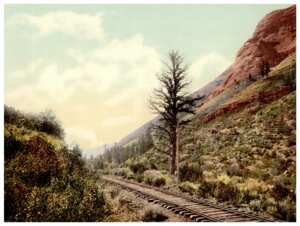

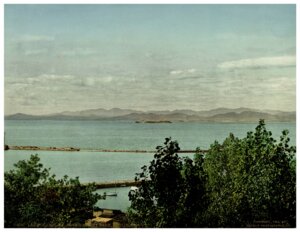

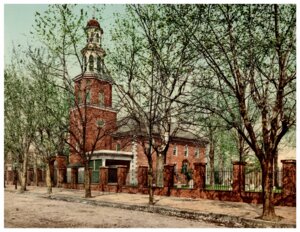

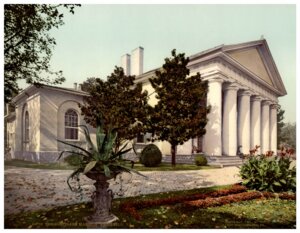

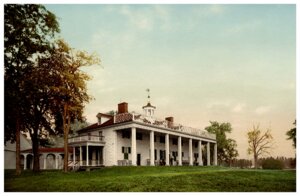

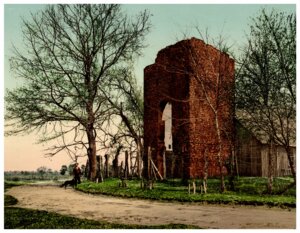

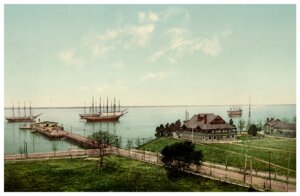

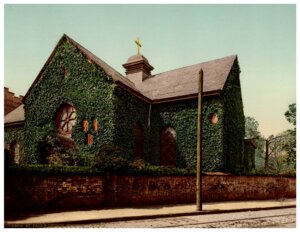

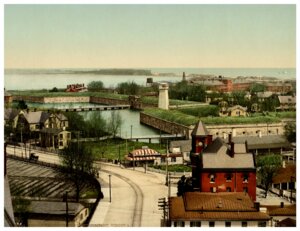

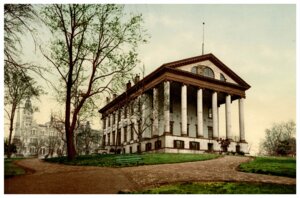

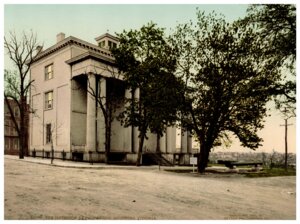

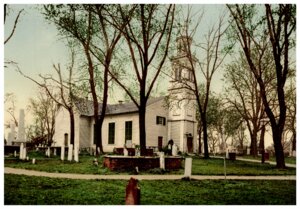

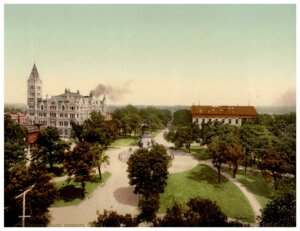

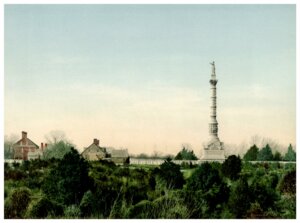

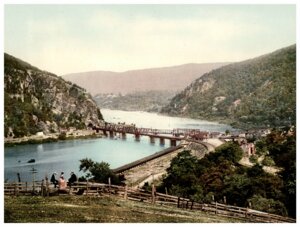

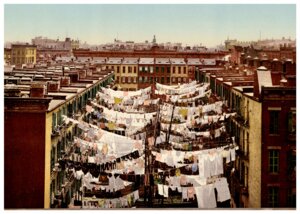

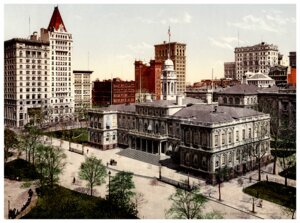

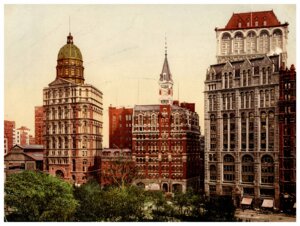

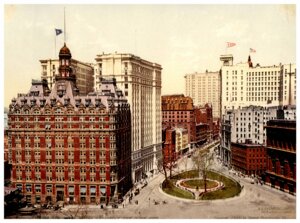

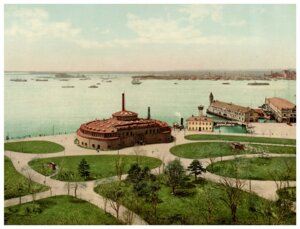

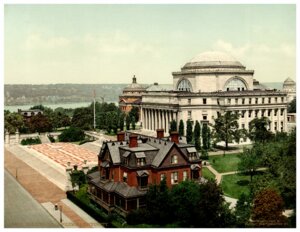

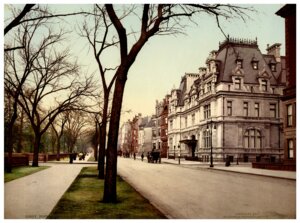

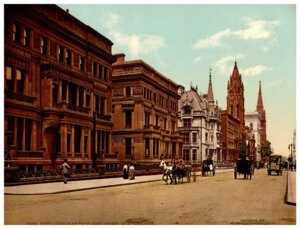

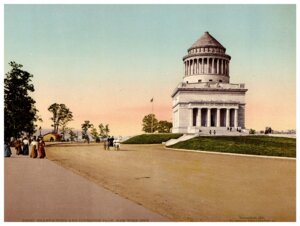

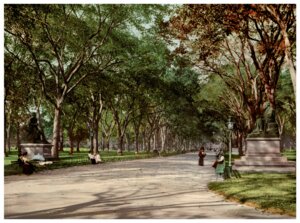

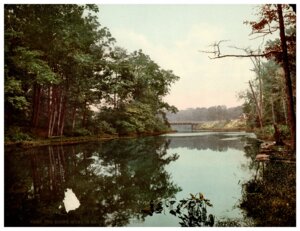

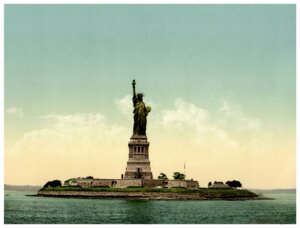

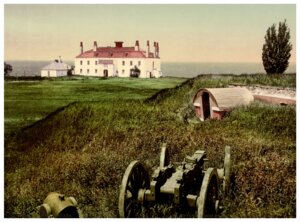

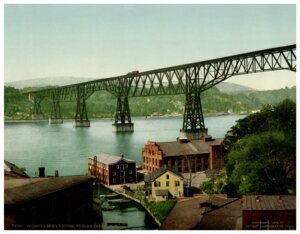

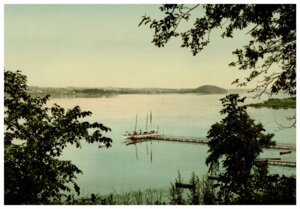

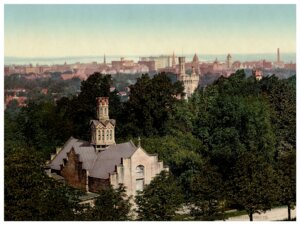

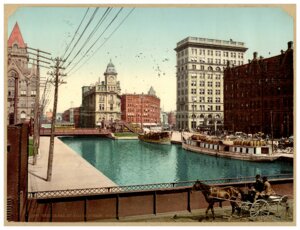

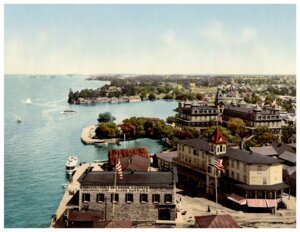

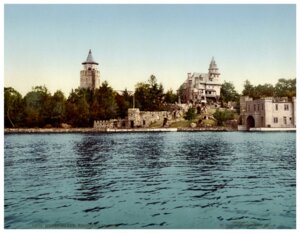

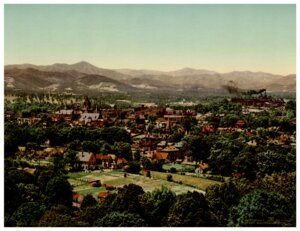

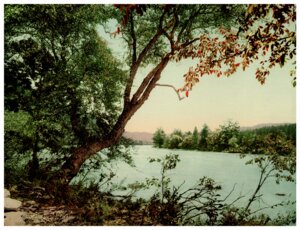

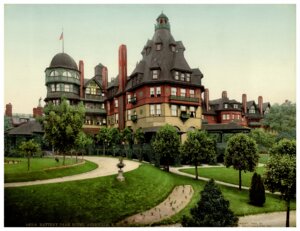

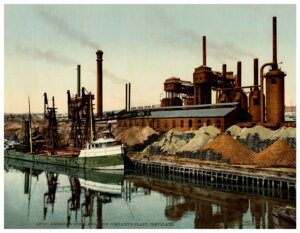

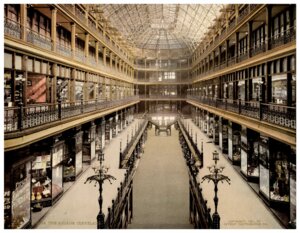

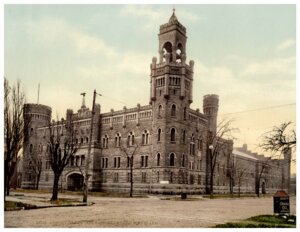

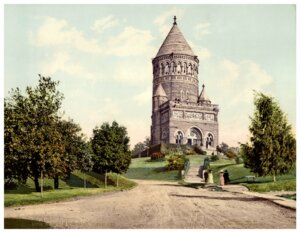

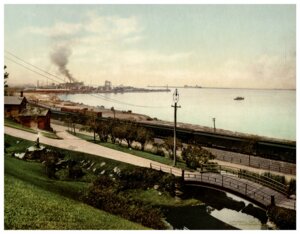

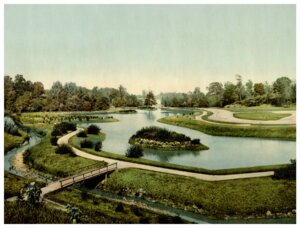

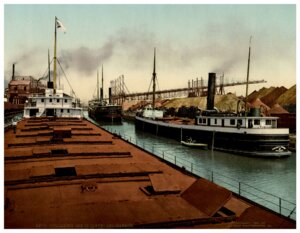

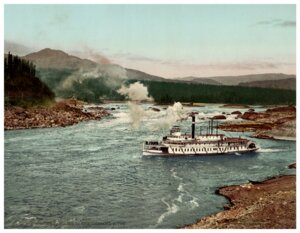

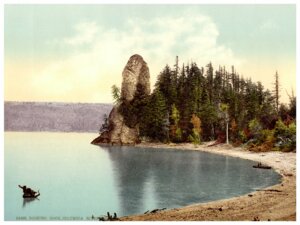

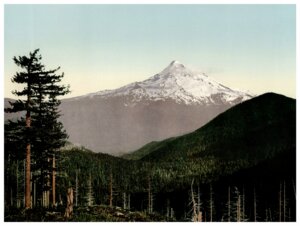

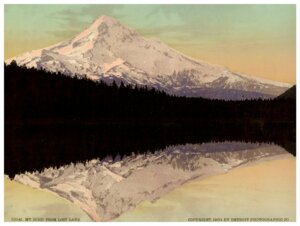

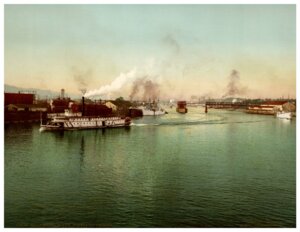

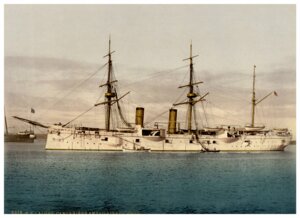

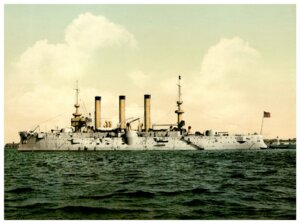

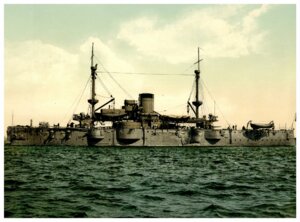

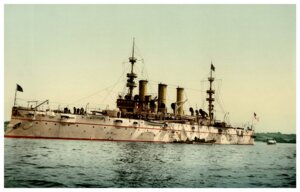

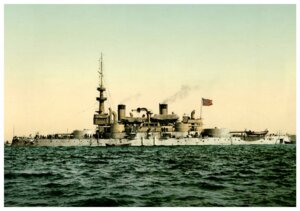

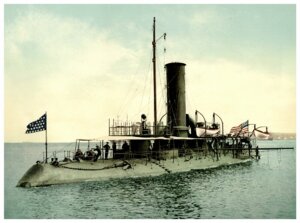

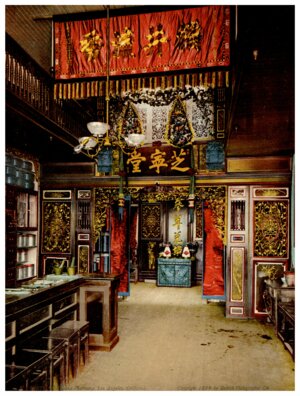

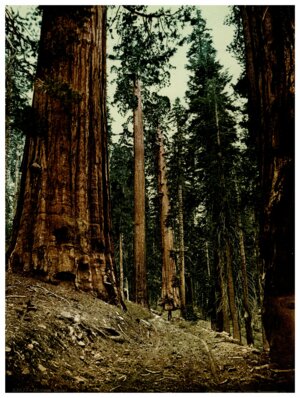

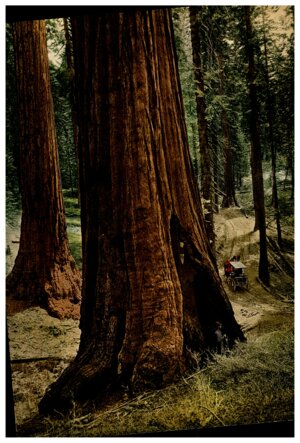

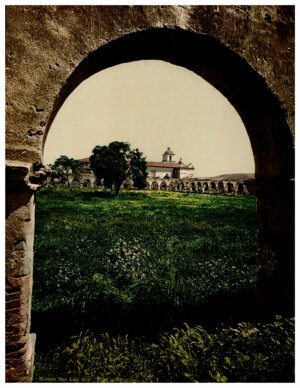

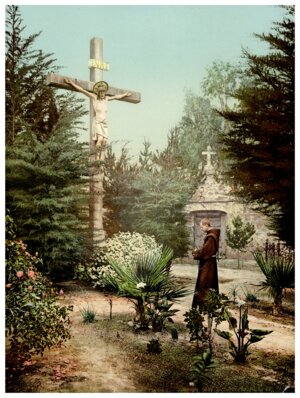

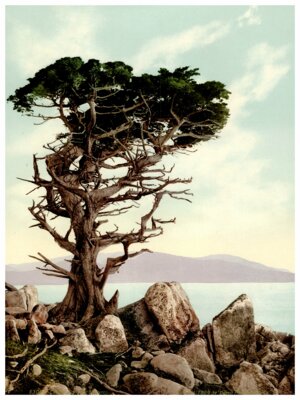

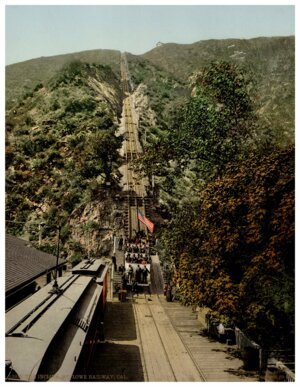

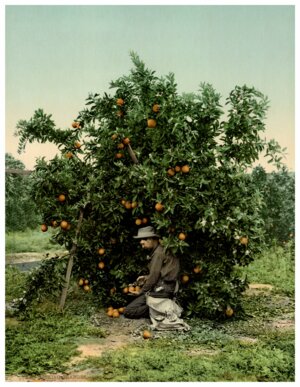

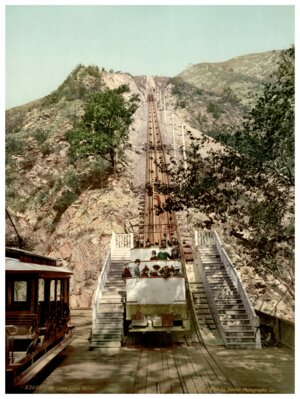

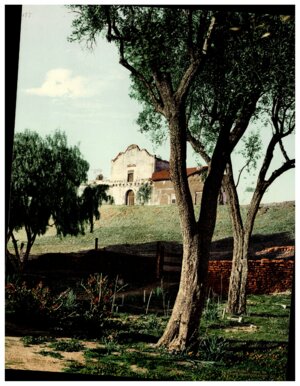

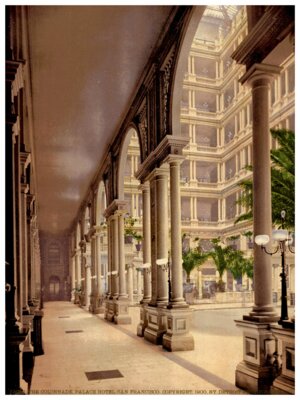

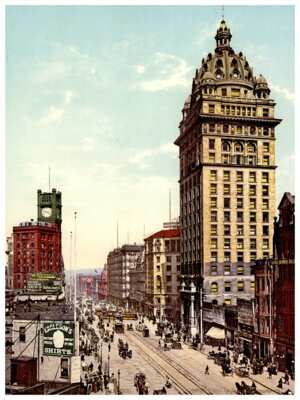

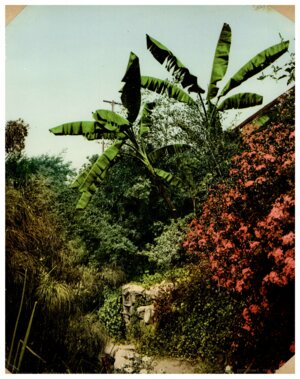

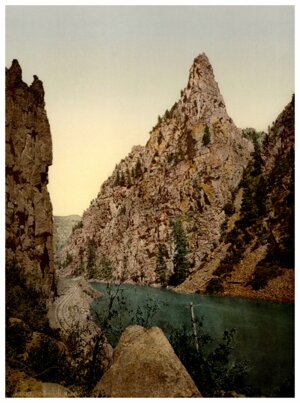

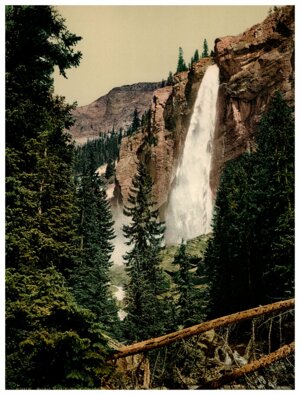

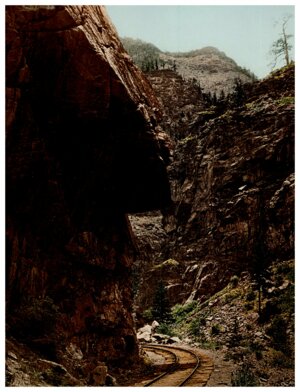

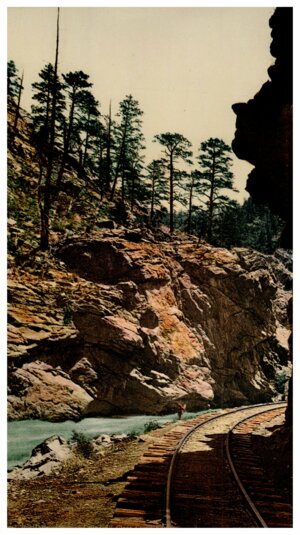

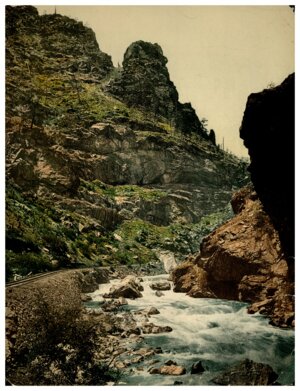

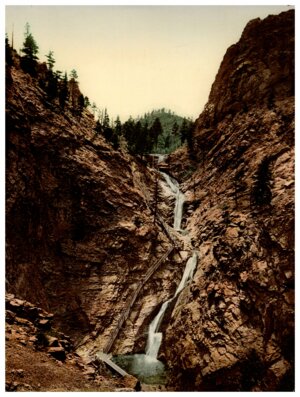

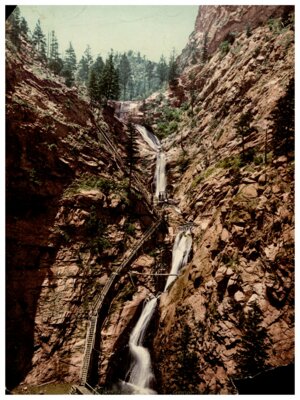

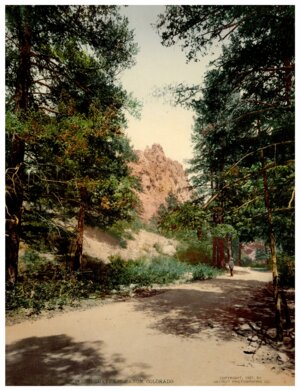

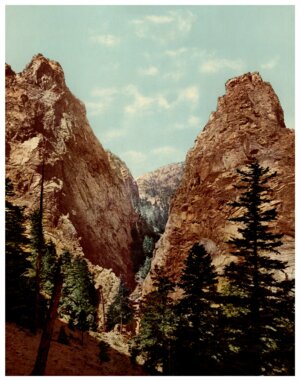

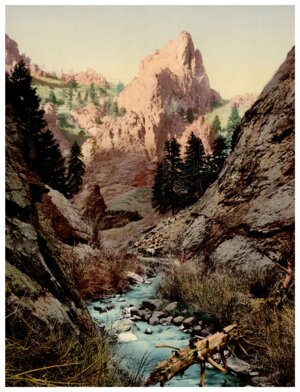

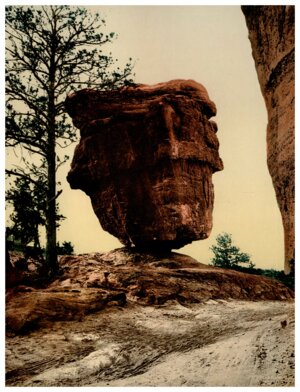

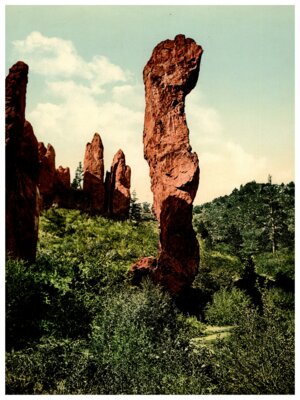

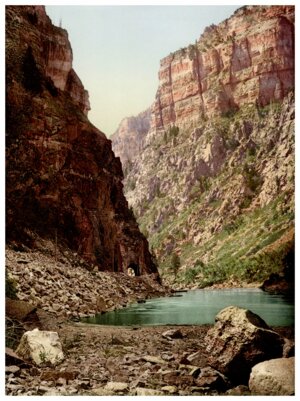

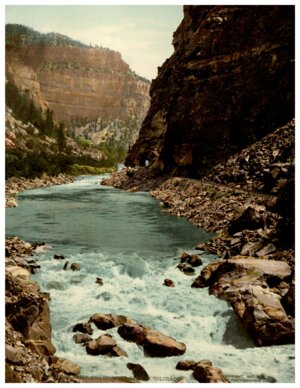

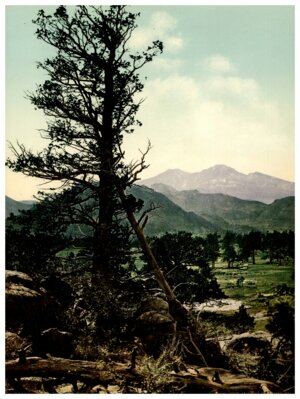

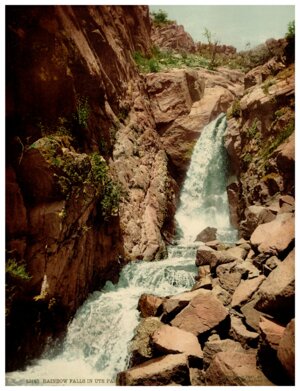

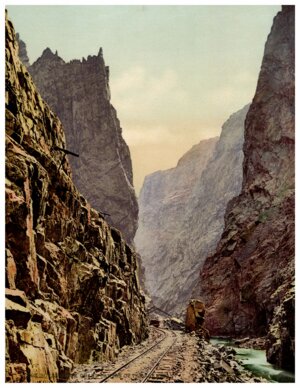

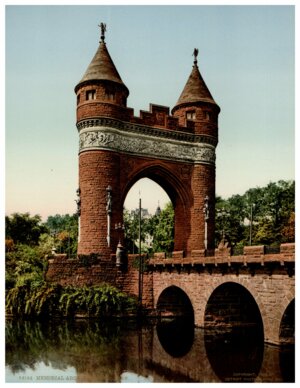

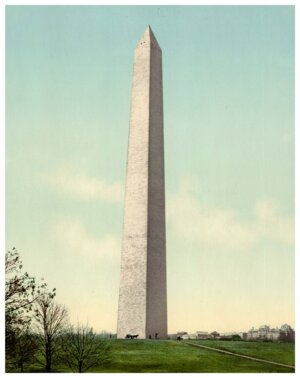

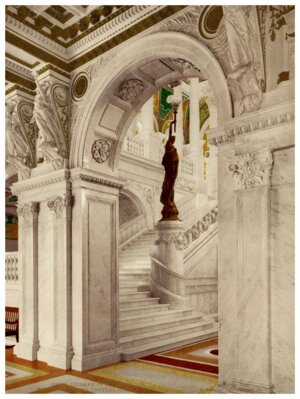

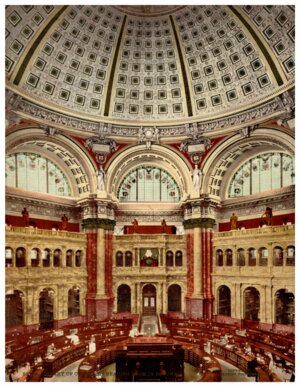

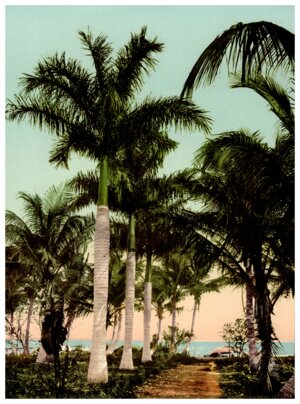

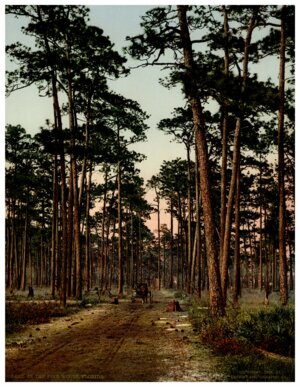

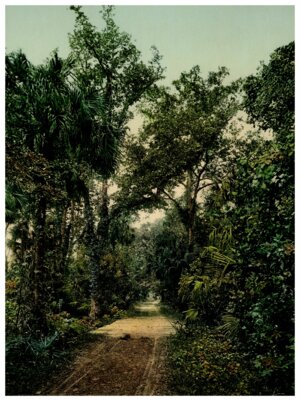

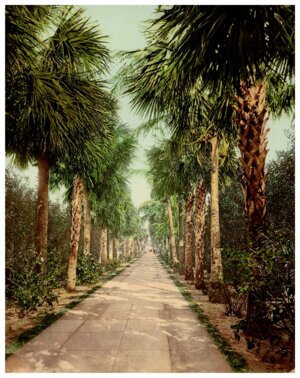

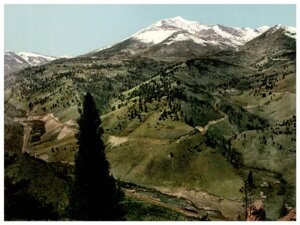

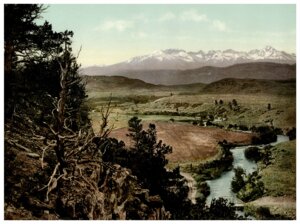

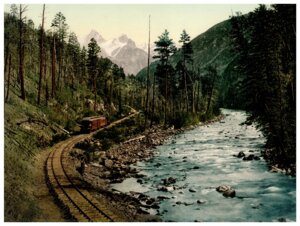

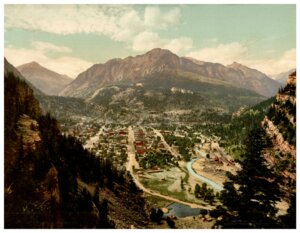

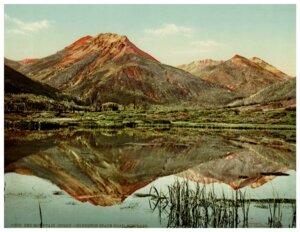

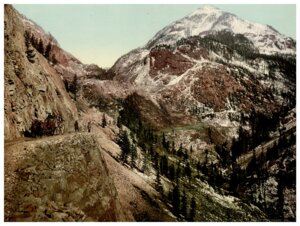

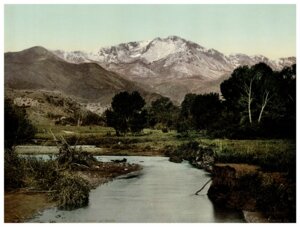

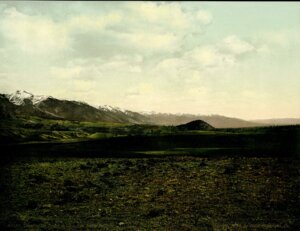

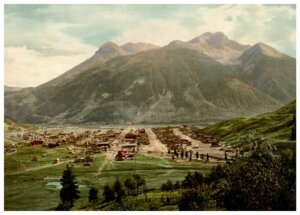

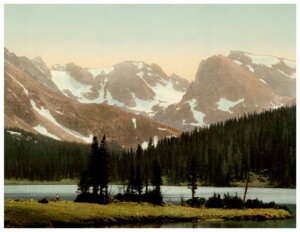

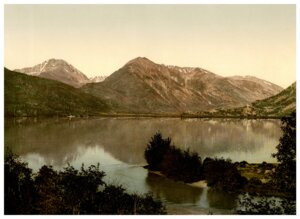

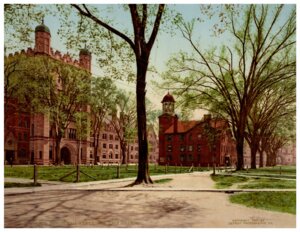

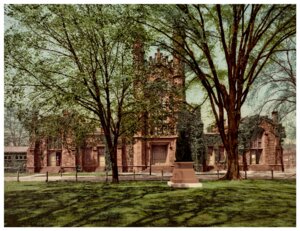

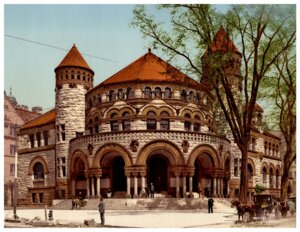

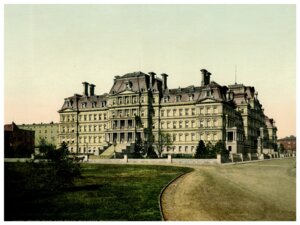

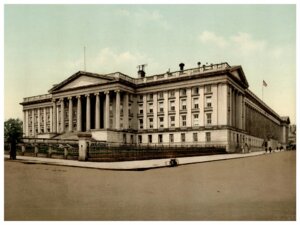

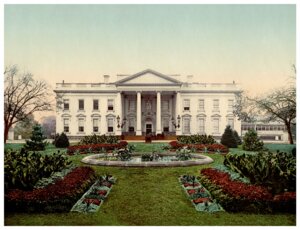

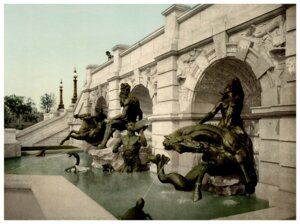

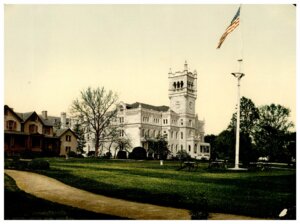

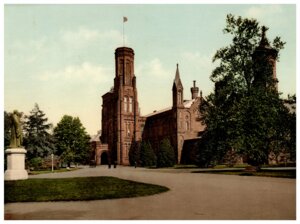

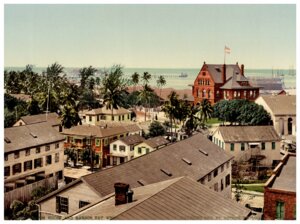

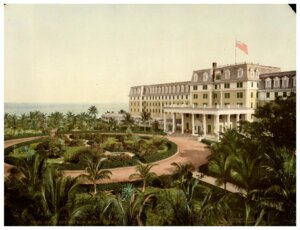

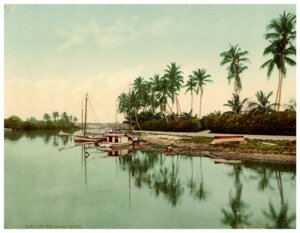

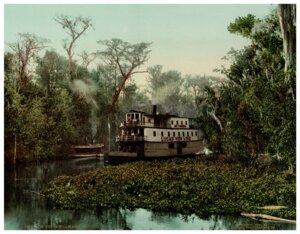

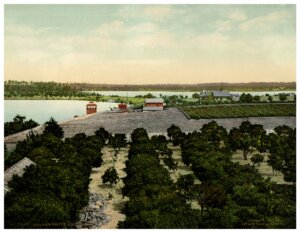

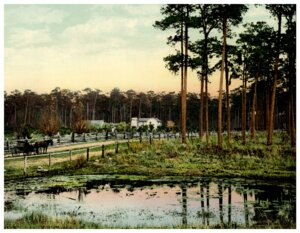

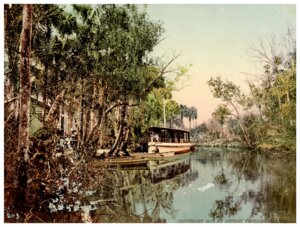

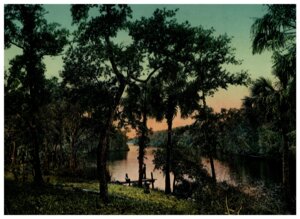

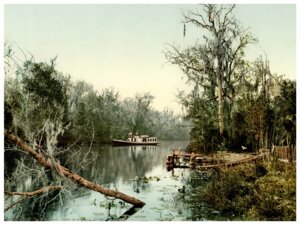

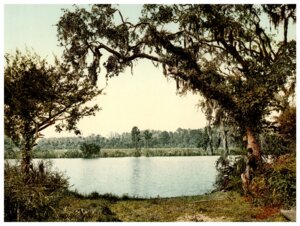

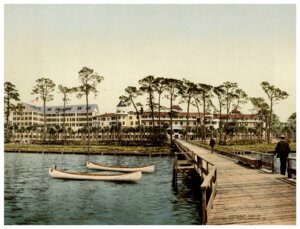

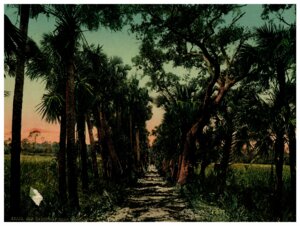

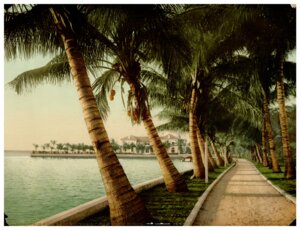

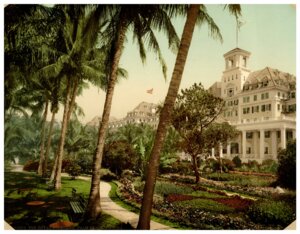

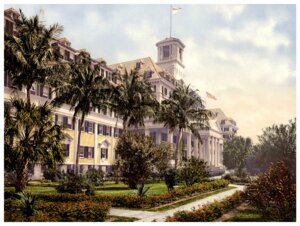

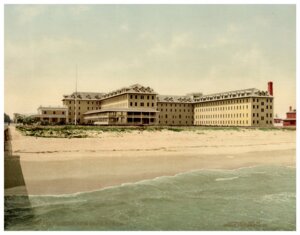

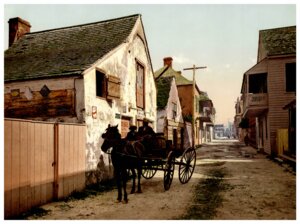

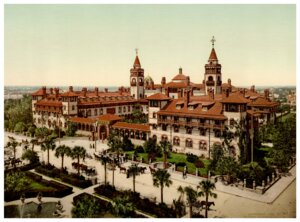

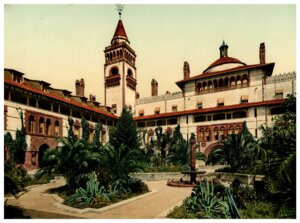

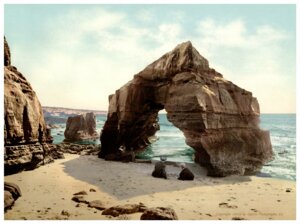

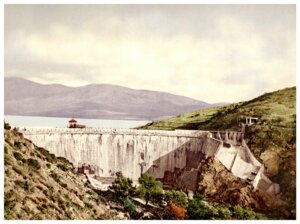

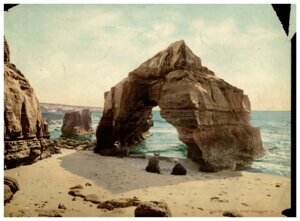

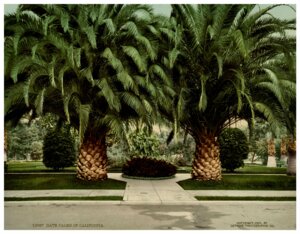

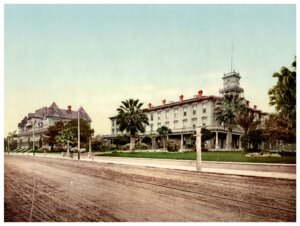

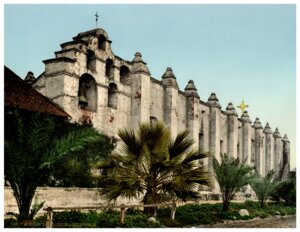

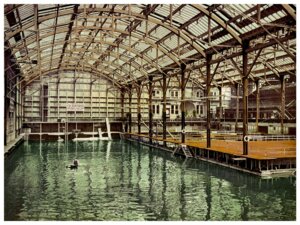

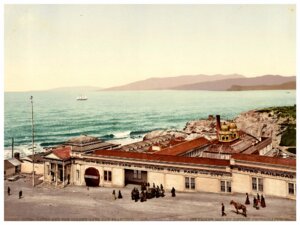

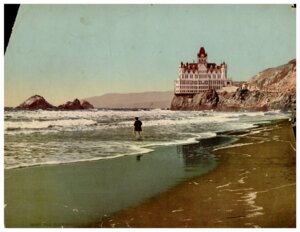

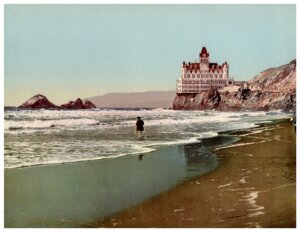

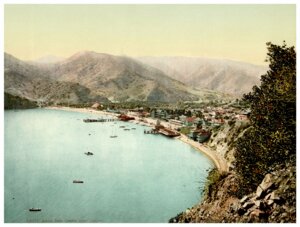

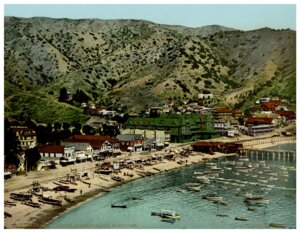

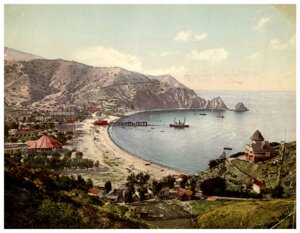

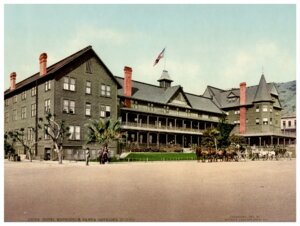

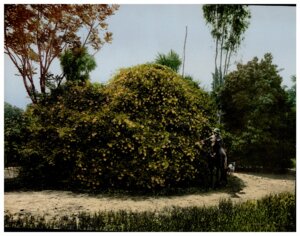

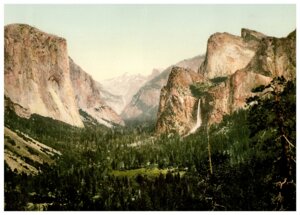

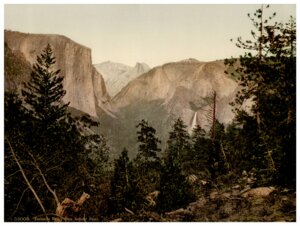

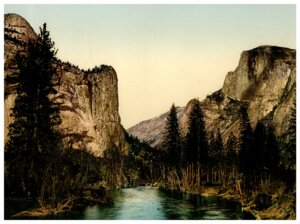

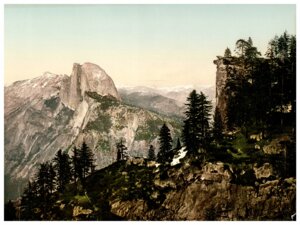

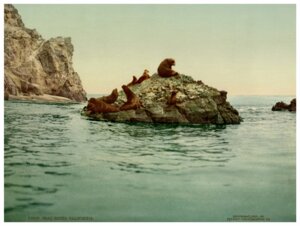

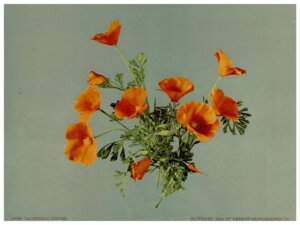

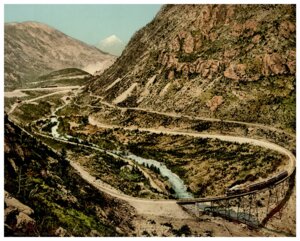

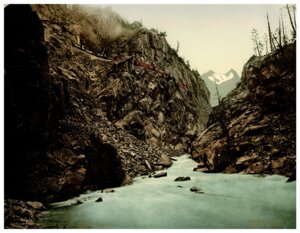

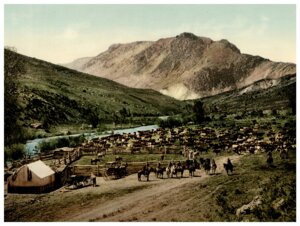

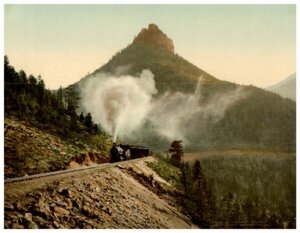

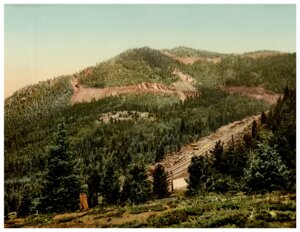

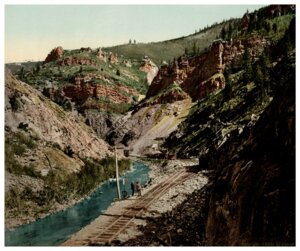

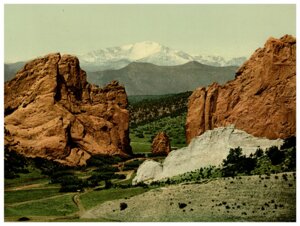

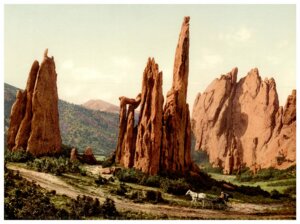

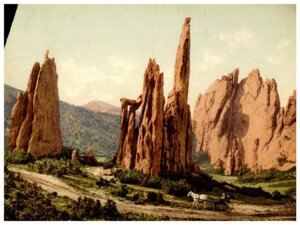

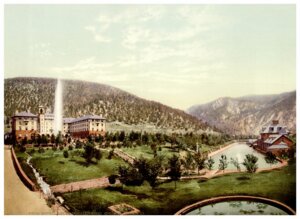

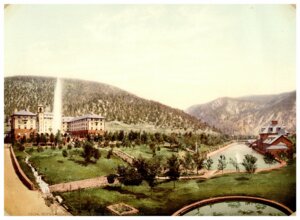

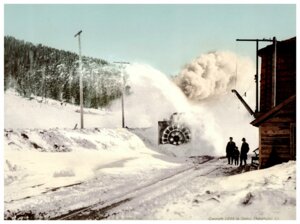

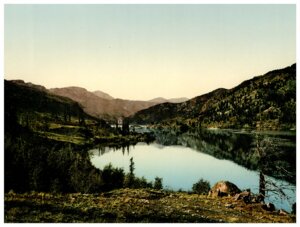

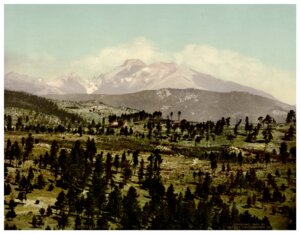

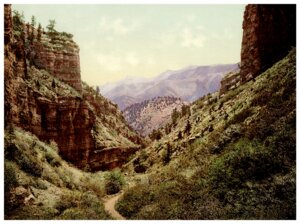

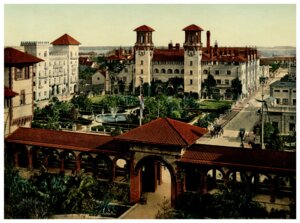

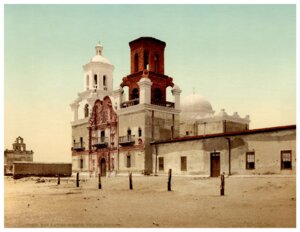

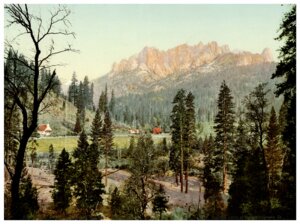

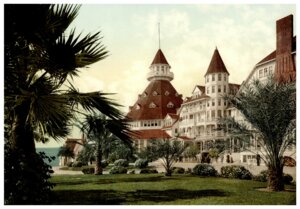

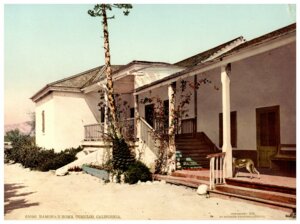

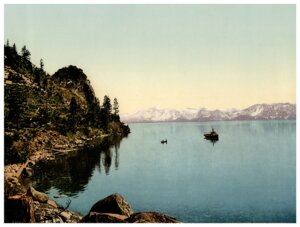

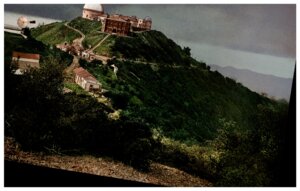

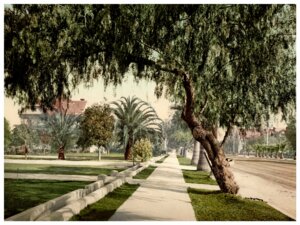

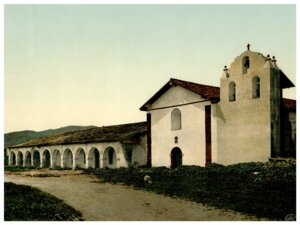

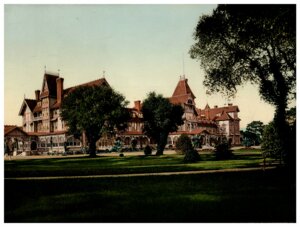

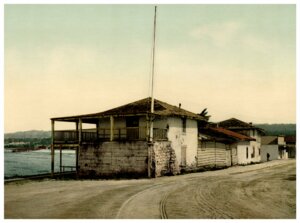

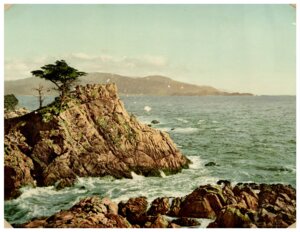

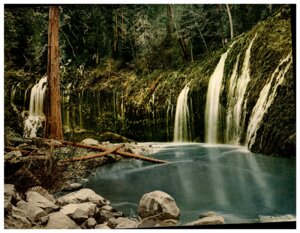

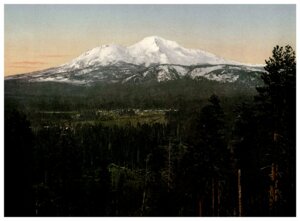

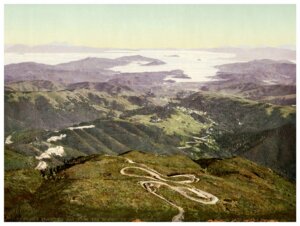

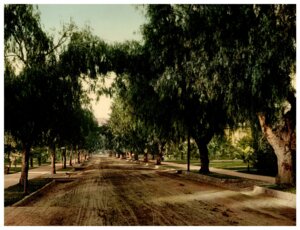

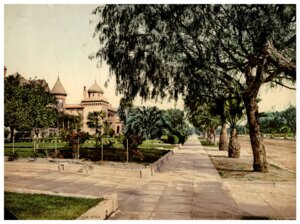

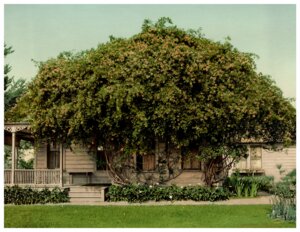

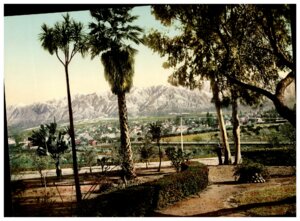

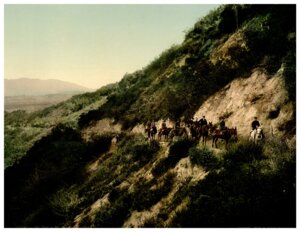

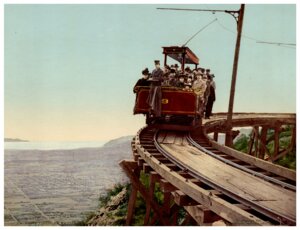

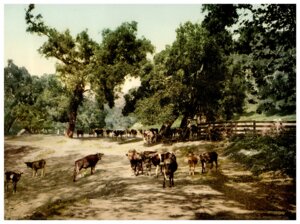

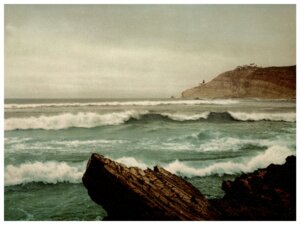

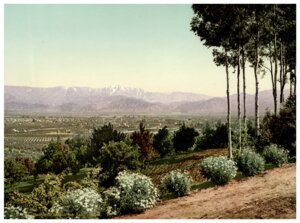

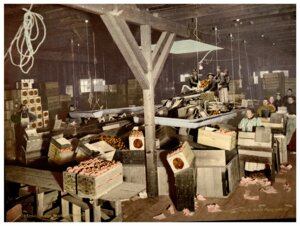

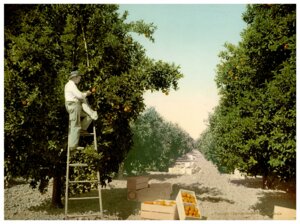

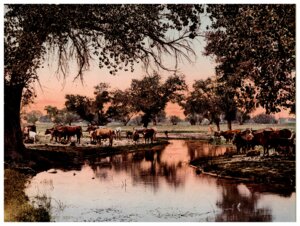

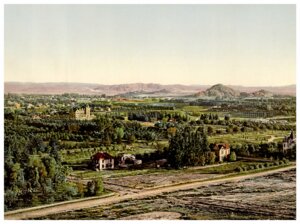

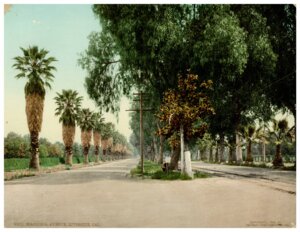

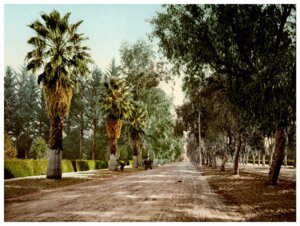

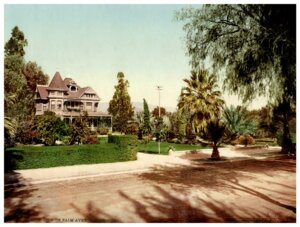

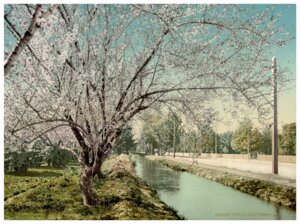

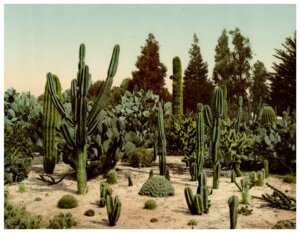

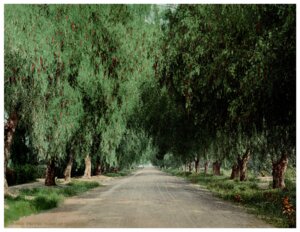

The Detroit Publishing Company was one of the world's leading image publishers for nearly 30 years. Between 1895 and 1924, she published portraits, landscapes or city views, mainly in the US. Are photographed large urban centers with San Francisco, New York, Cleveland, Philadelphia or Detroit, places of leisure with the beaches of California, Florida or Atlantic City or the diversity of American vegetation. The latter often forms a composition with elements of modernity: railways, factories or ships. Also, photographers immortalize the monuments of Washington, the grandiose landscapes of Colorado or more rural cities like Williamsburg. Finally, trips will be an opportunity to take views of neighboring countries such as Mexico, Cuba or Canada. This collection of more than 1150 images constitutes a representative fraction of the diversity of the company's productions.

HISTORICAL

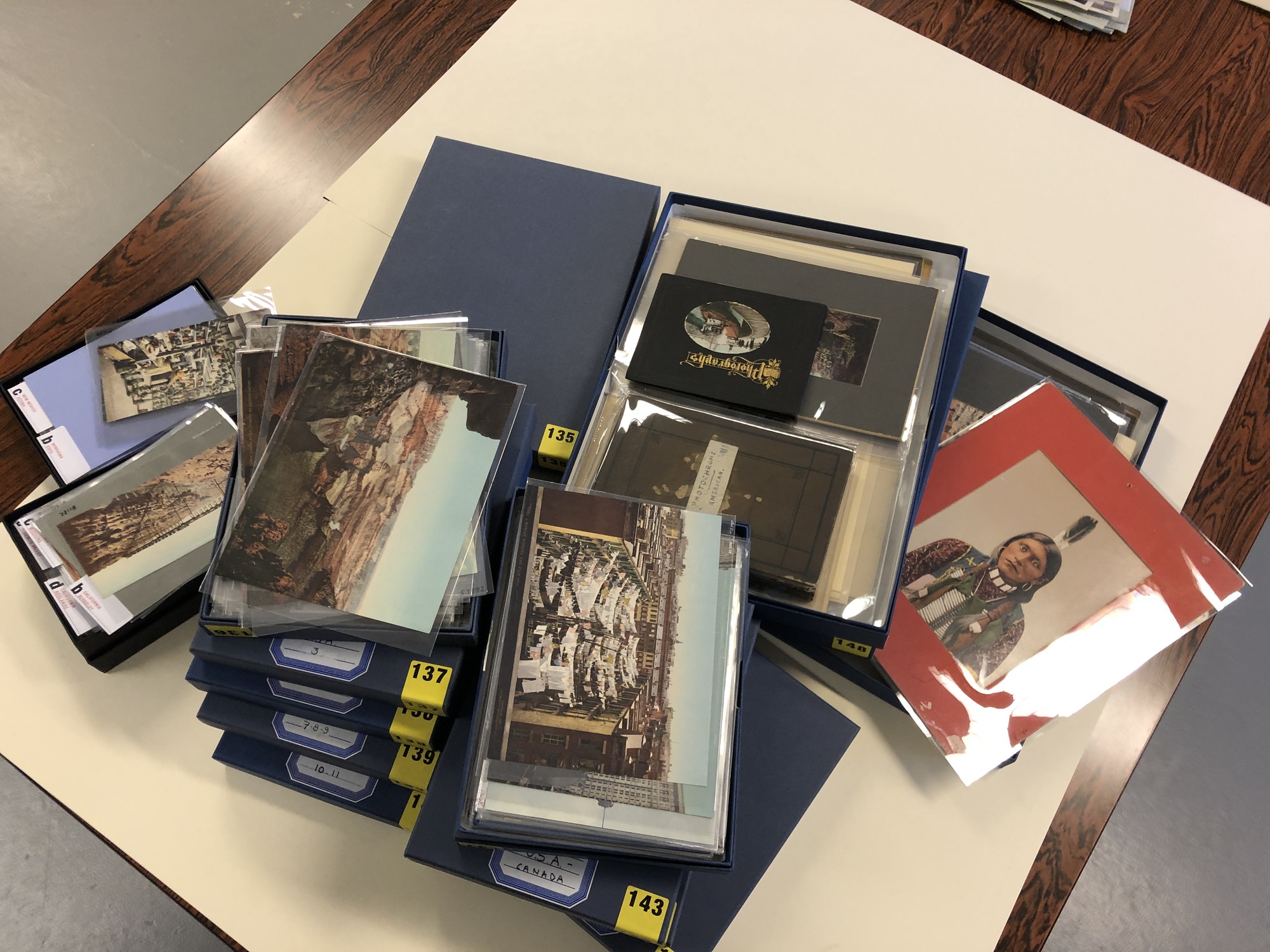

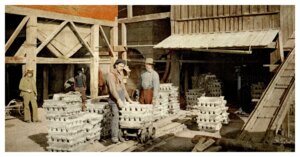

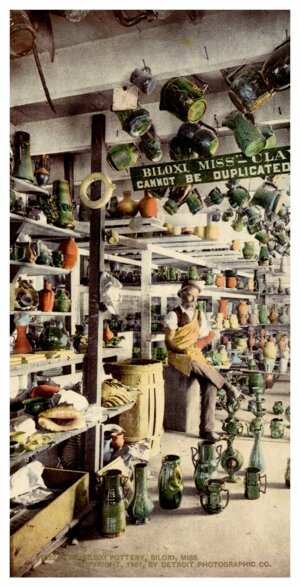

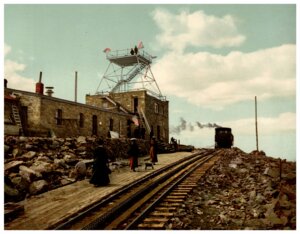

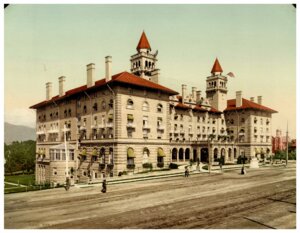

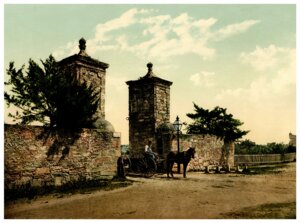

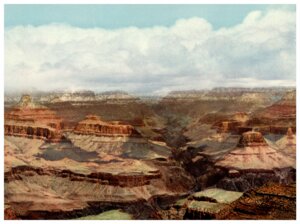

In 1895, William A. Livingstone partnered with Edwin H. Husher to form the Detroit Publishing Company in Michigan. This company was divided into two main activities: on the one hand the Photographic Company centered on the production of photographs and on the other hand the Photochrom Company which dealt with color prints. It is this process, purchased from the Photoglob Company of Zurich, which will make them successful. Indeed, It will be declined in the form of postcards, sepia photos or lantern slides. The process is a form of photolithography that required 16 colors to produce the final image. The entire process of creating photochromes is not yet known and research has been going on since the 1990s to reconstruct the process. Be that as it may, if the latter allows the company to sell up to 7 million prints per year, it will also be the cause of its downfall. With the appearance of simplifying techniques and its qualification as an activity not essential to the war effort by the government, the company was finally placed in receivership in 1924.

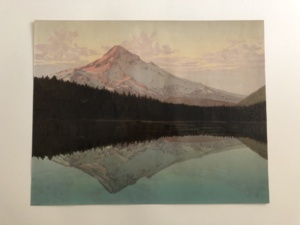

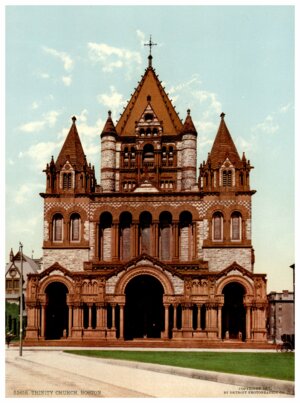

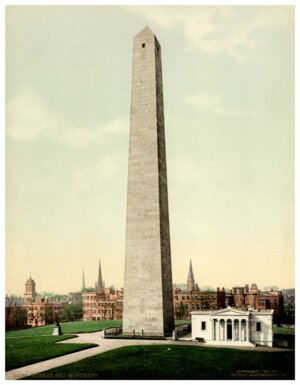

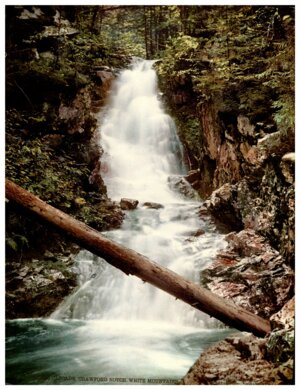

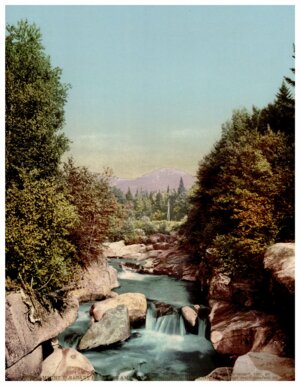

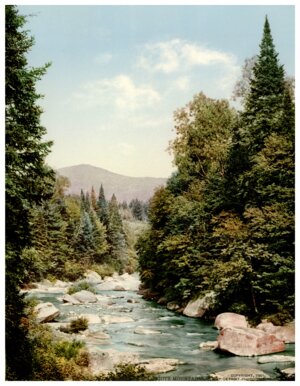

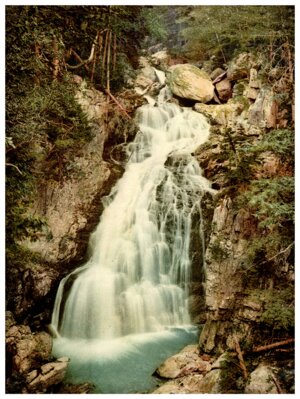

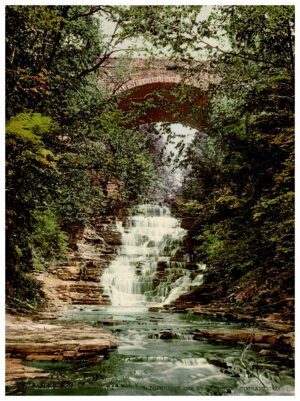

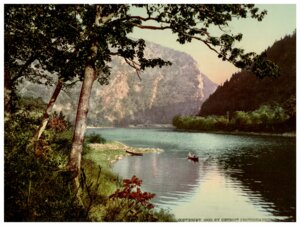

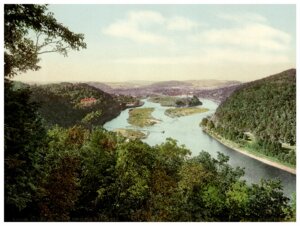

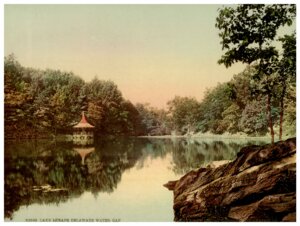

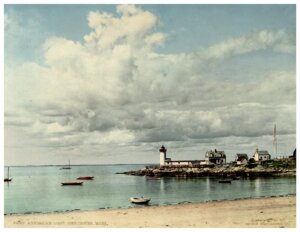

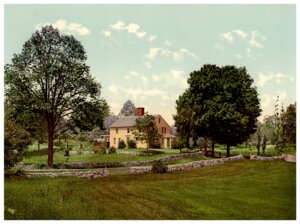

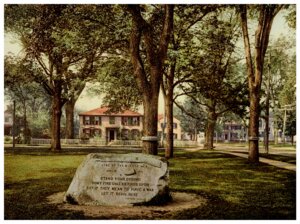

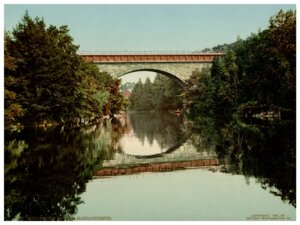

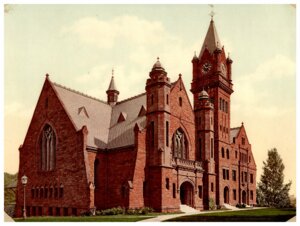

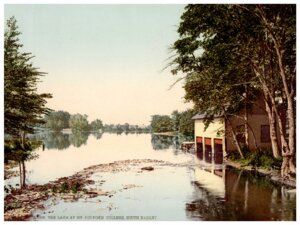

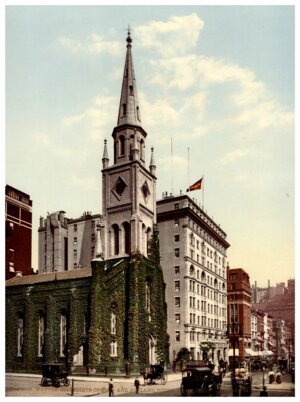

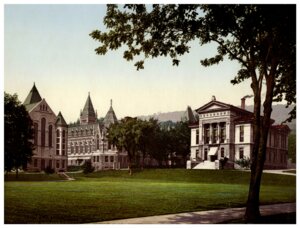

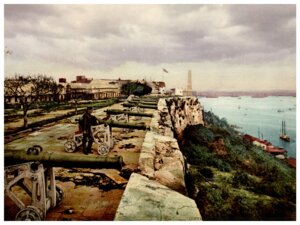

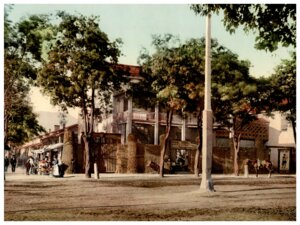

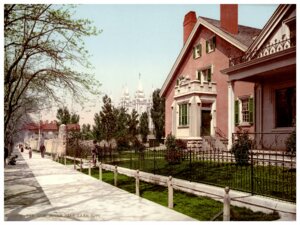

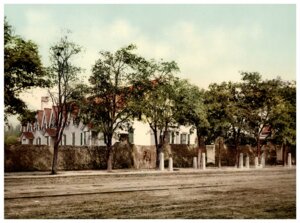

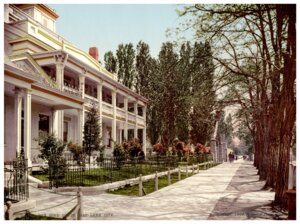

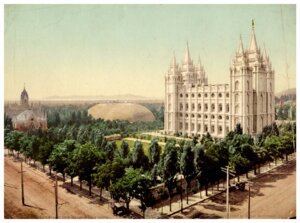

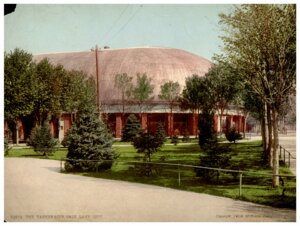

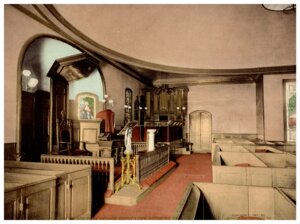

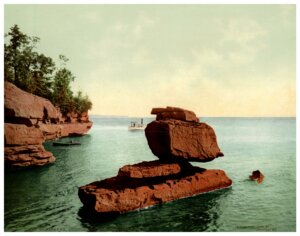

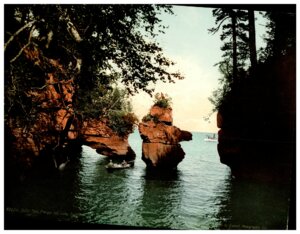

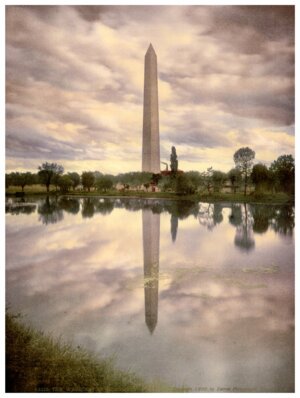

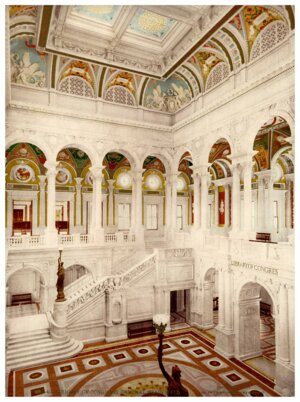

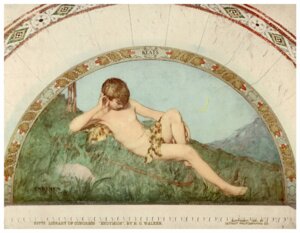

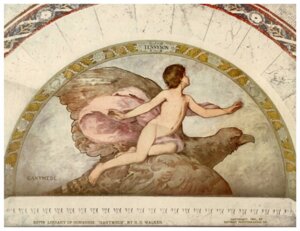

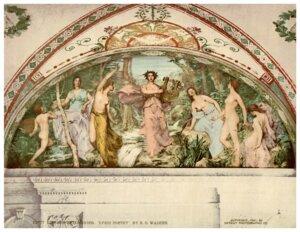

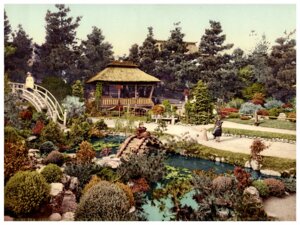

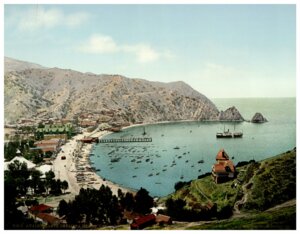

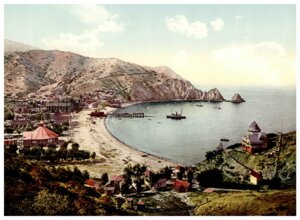

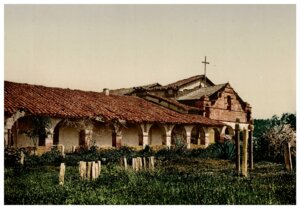

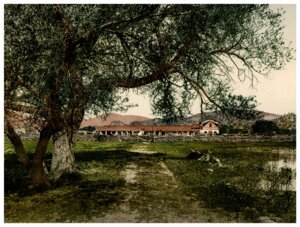

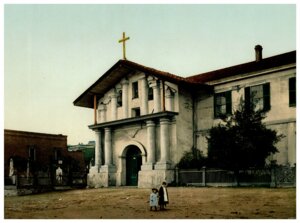

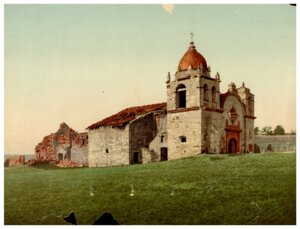

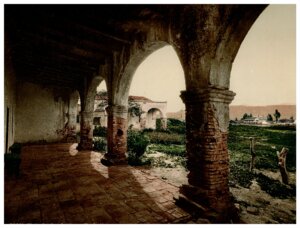

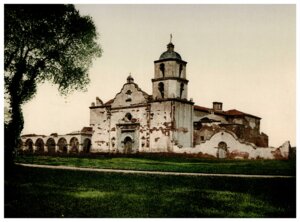

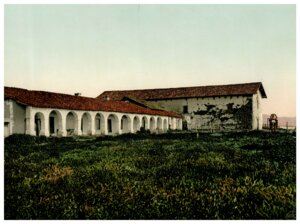

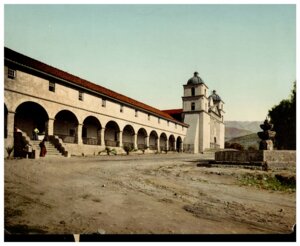

PHOTOCHROMES

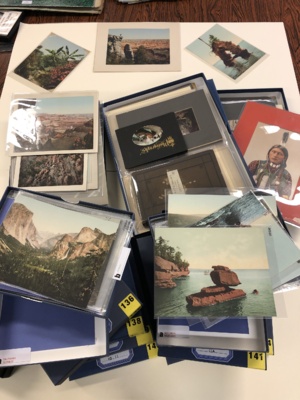

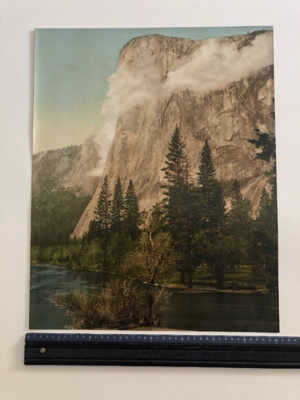

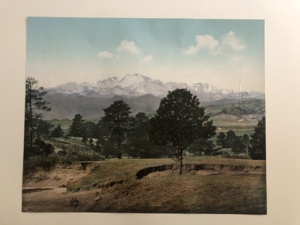

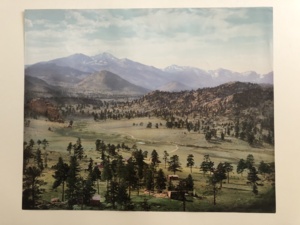

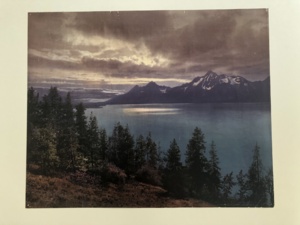

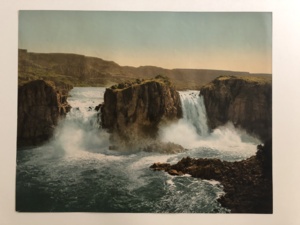

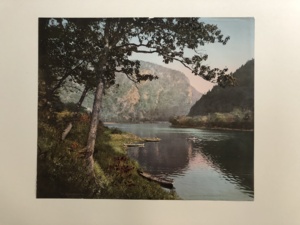

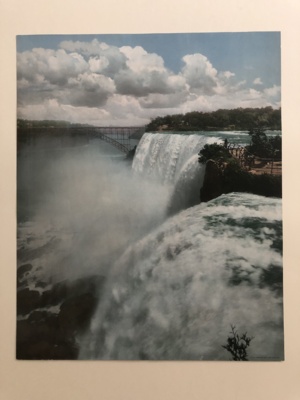

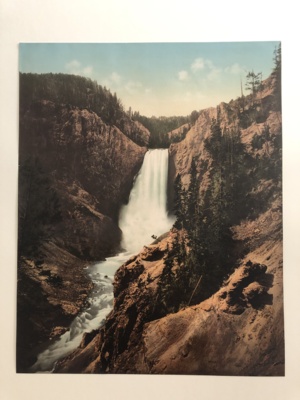

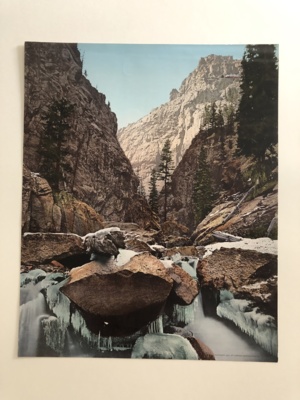

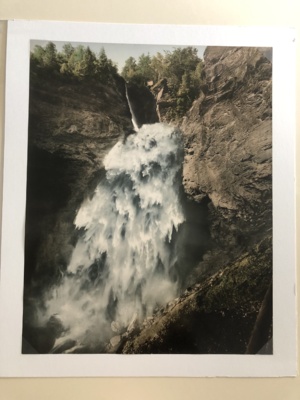

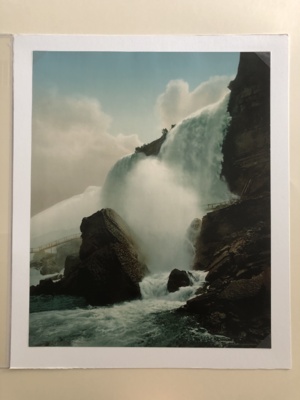

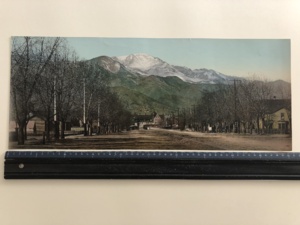

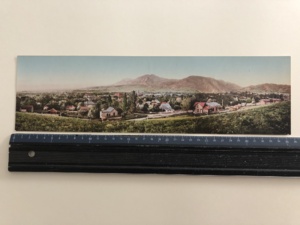

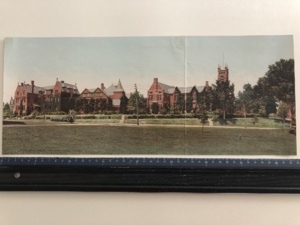

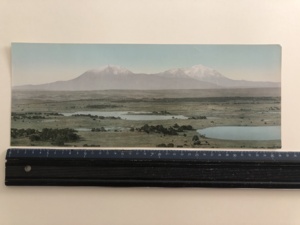

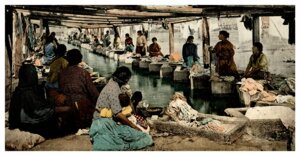

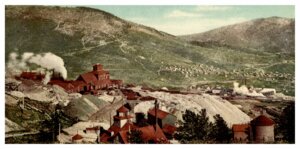

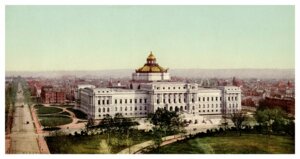

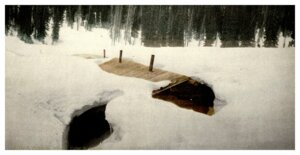

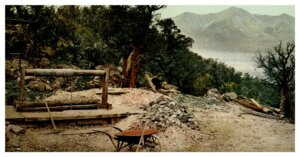

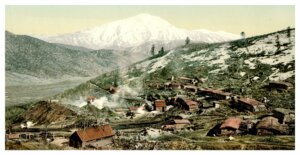

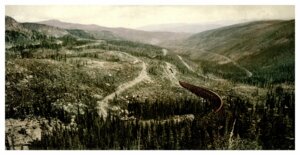

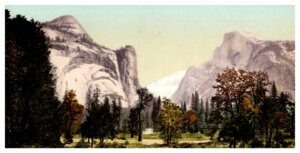

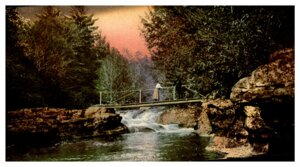

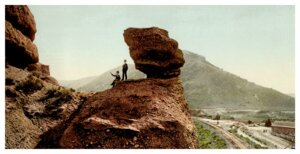

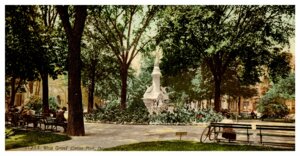

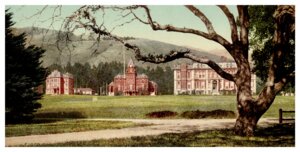

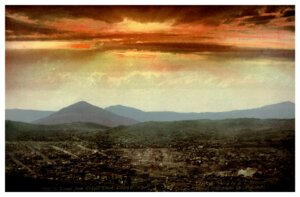

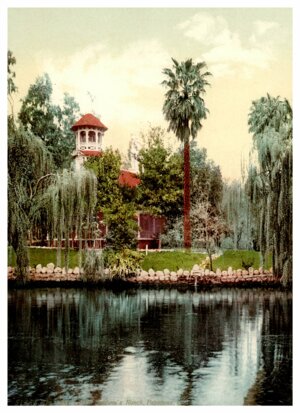

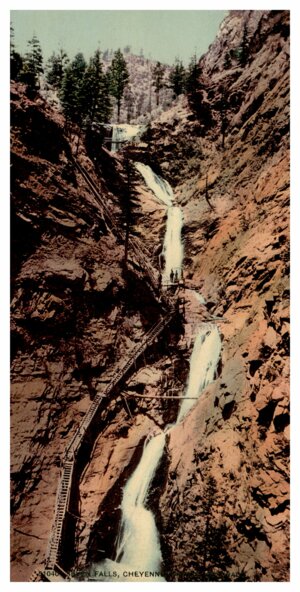

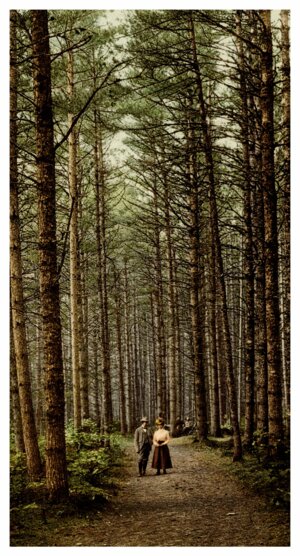

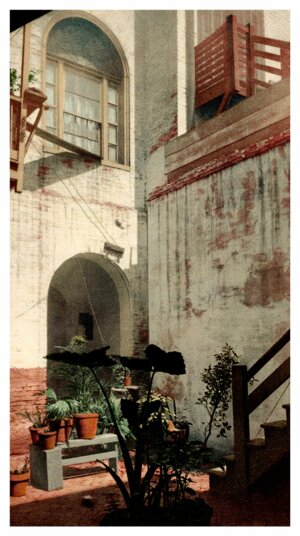

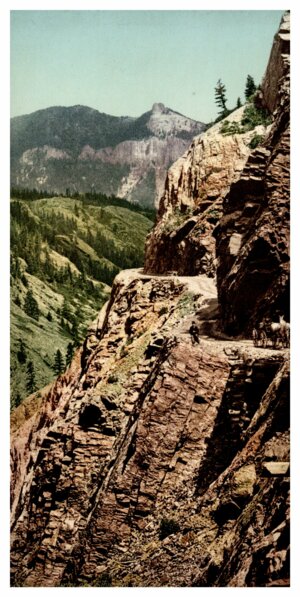

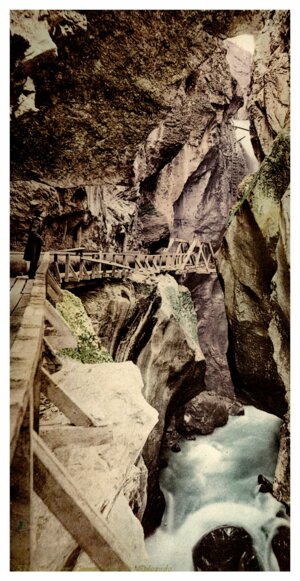

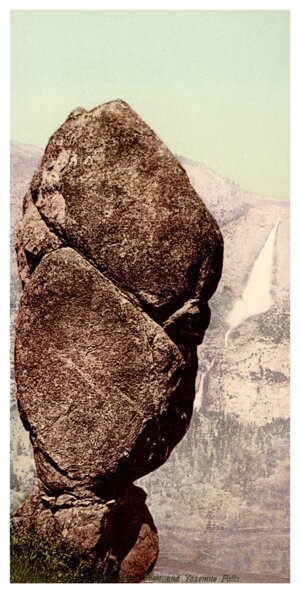

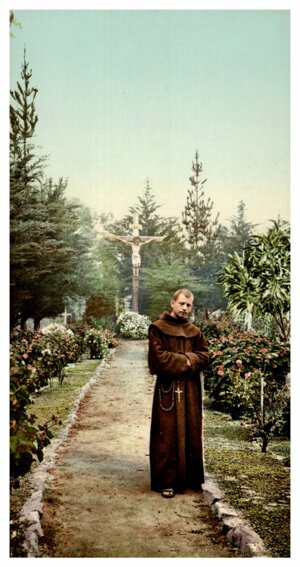

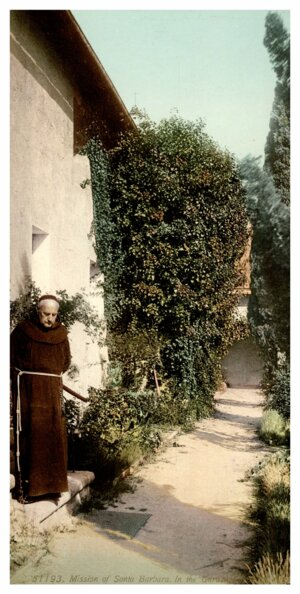

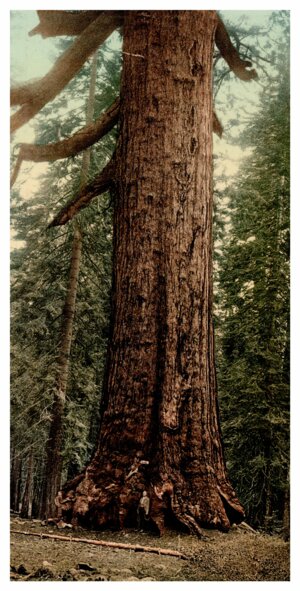

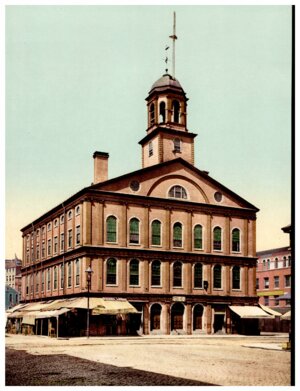

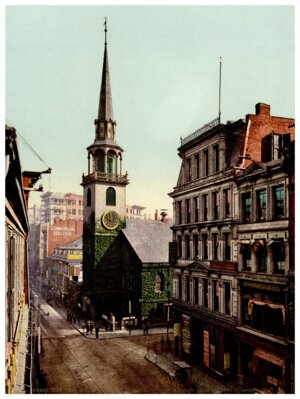

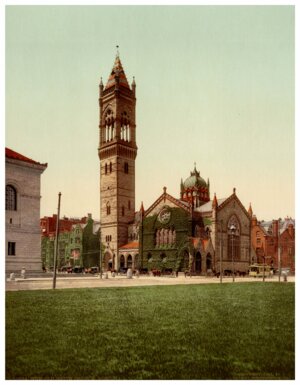

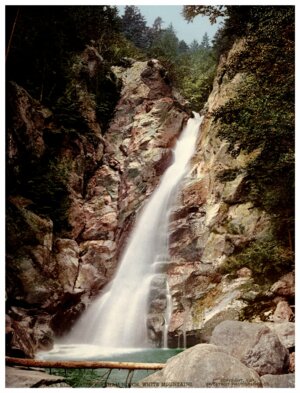

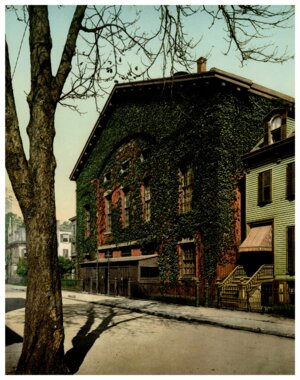

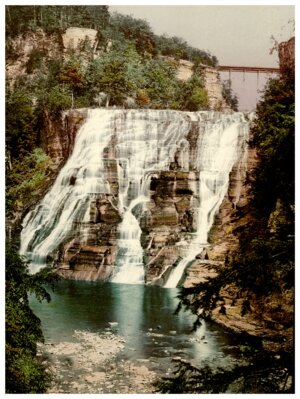

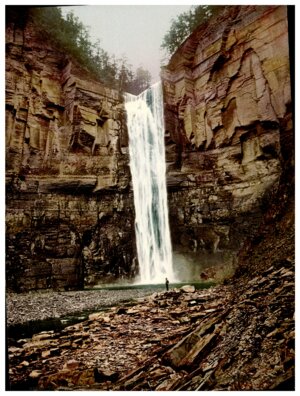

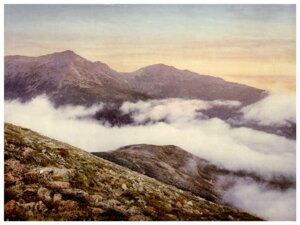

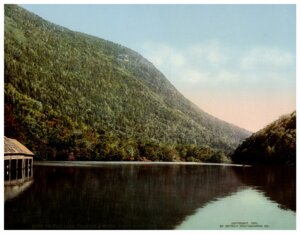

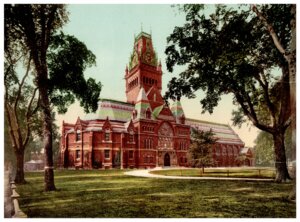

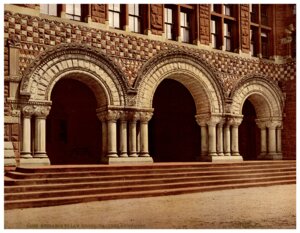

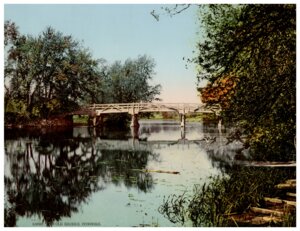

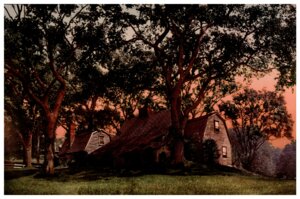

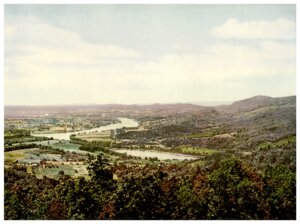

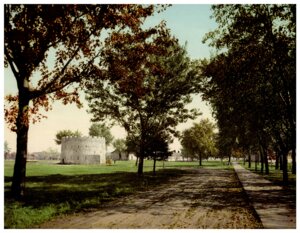

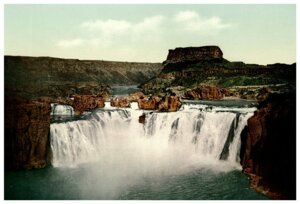

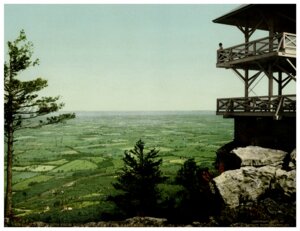

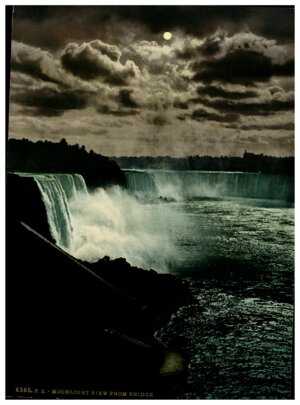

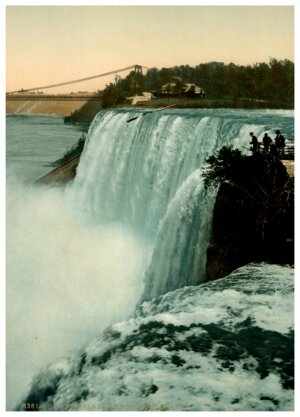

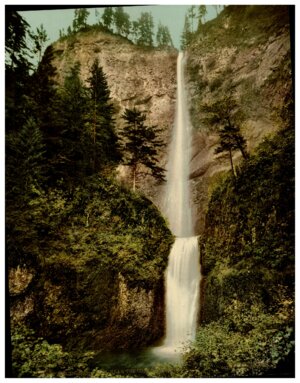

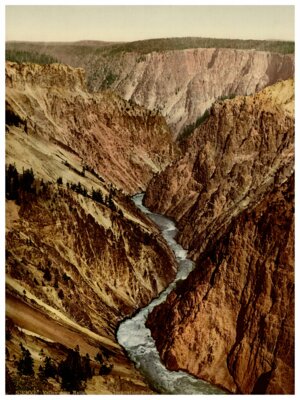

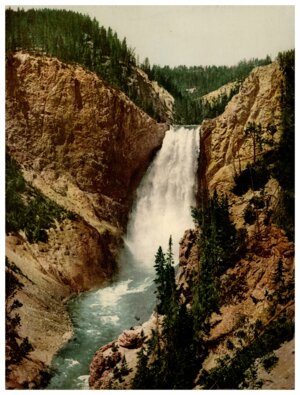

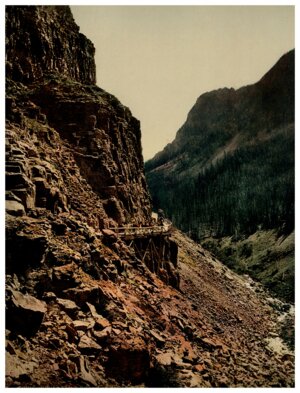

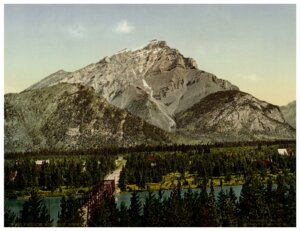

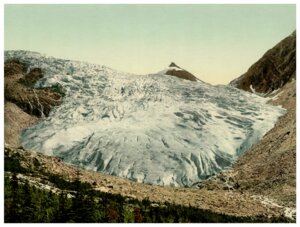

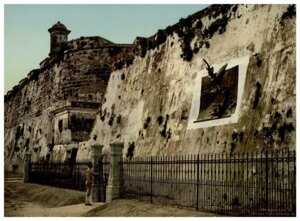

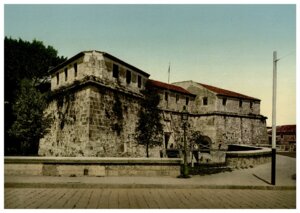

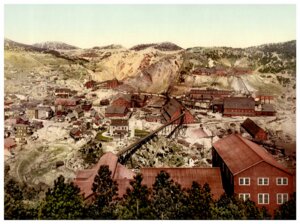

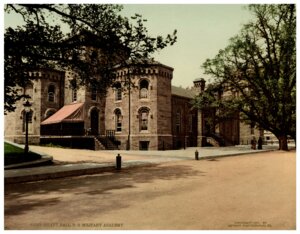

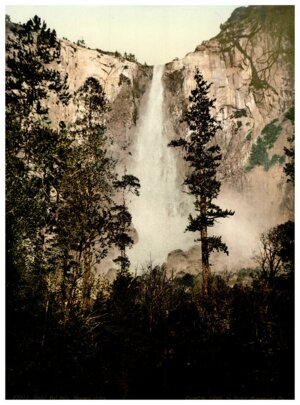

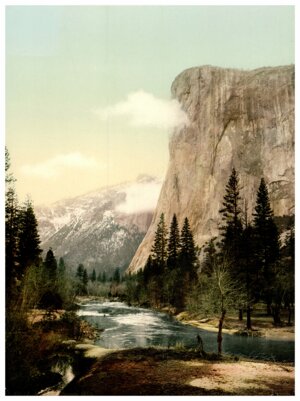

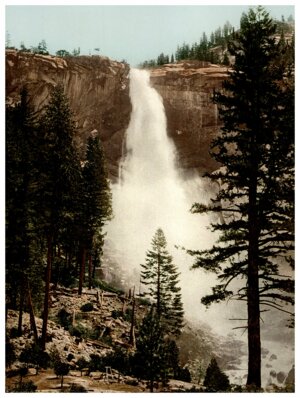

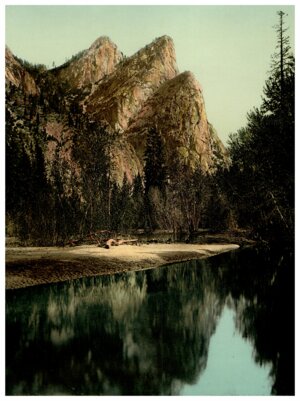

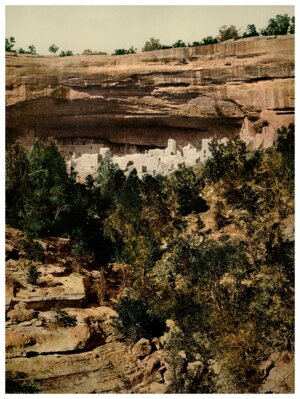

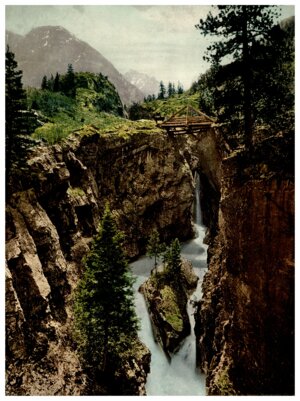

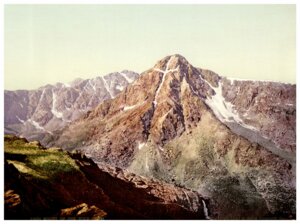

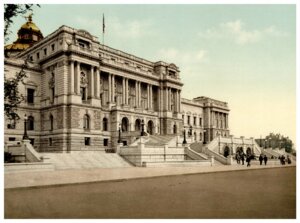

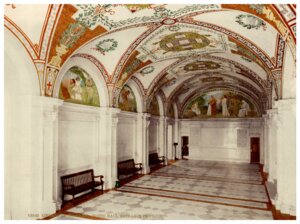

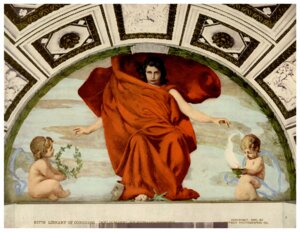

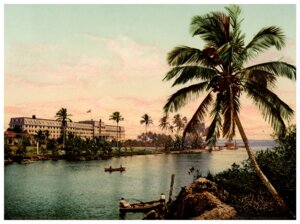

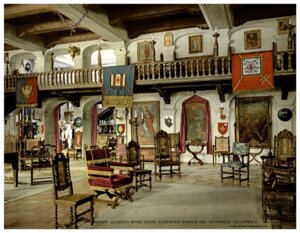

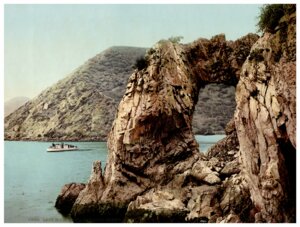

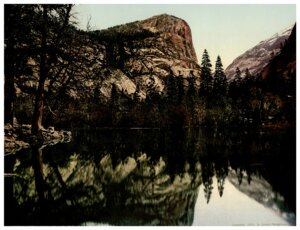

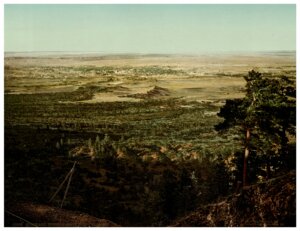

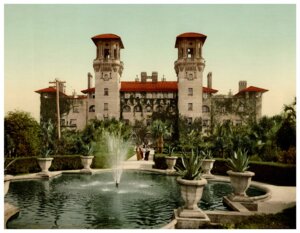

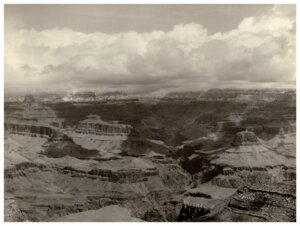

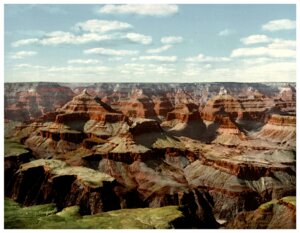

Regarding their material characteristics, the photochromes, mainly made between 1897 and 1914, are slightly shiny. They can be mounted on cardboard, and very often include a legend in golden letters placed under the image which makes it possible to identify the view, or even the photographer. At the height of its glory, the company had a collection of around 40,000 very diverse negatives including views of cities, landscapes, events and leisure activities. These views were also used for advertising purposes or sold to museums, libraries and schools. When It wanted to produce a new photochrome, It was from this pool of black and white photographs that the DPC drew. In fact, frequently, indications as to the choice of color are found on the back of the black and white photographs. As for their size, the large colored formats can measure up to 55 cm in length and up to 65 cm in length for panoramas such as that of Cripple Creak in Colorado also preserved at the Library of Congress in Washington. This use of large formats makes it possible to better transcribe the immensity of the places to those who contemplate the photograph.

WILLIAM H. JACKSON (1843-1942)

Several photographers have worked with the company such as Henry Greenwood Peabody, Lycurgus S. Glover, Edward H. Hart or John S. Johnson.

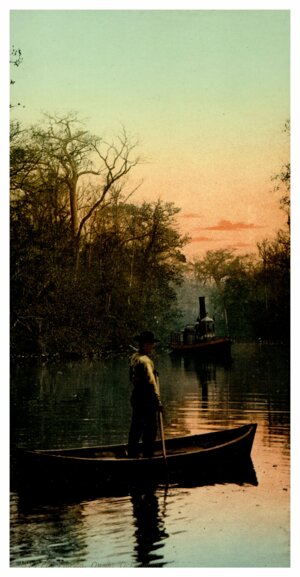

Nevertheless, the keystone of this success was pioneer American photographer William Henry Jackson. The latter joined the venture in late 1897 and produced 10,000 glass plates to enrich the company's fund. Moreover, he was not only making prints himself but also buys back the funds of the photographers he meets during his travels in the US, Canada or the Caribbean.

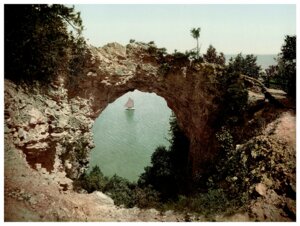

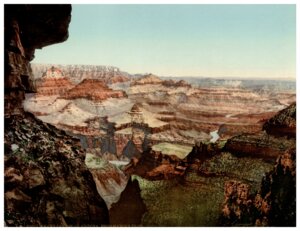

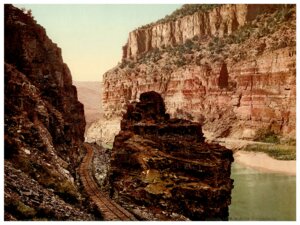

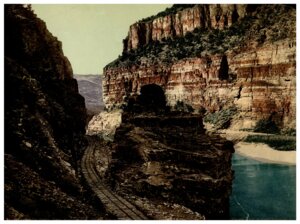

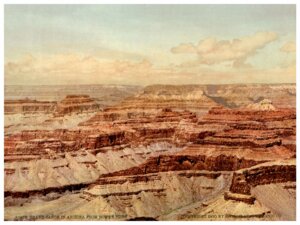

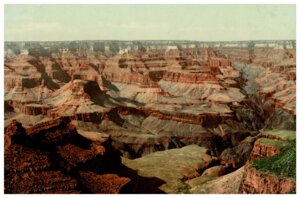

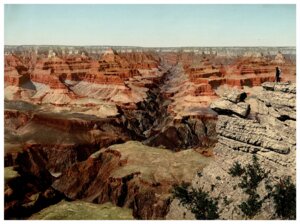

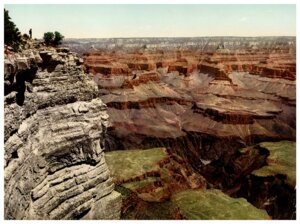

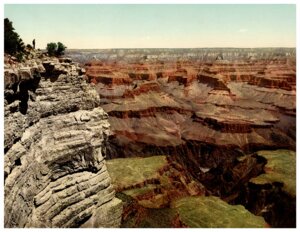

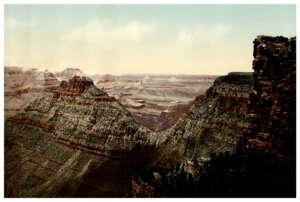

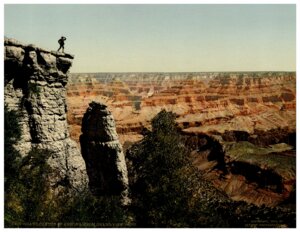

Jackson was the first to make color prints of the Grand Canyon, discovered in 1850. This earned him a personal success that reflected on the company. In addition, his autobiography entitled Time Exposure is highly instructive on the functioning of the DPC and on its aesthetic formation. Published in 1940, he recounts at length his military past and his passion for landscape painting. It appears from this story that Jackson was constantly using his sketchbook which allowed an early development of his talent for the snapshot.

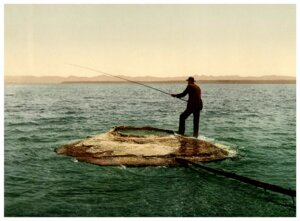

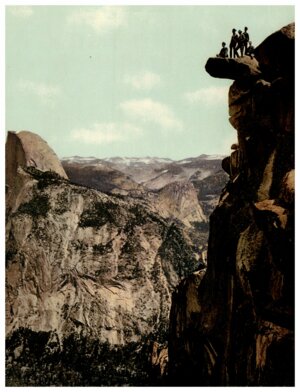

Defining himself as "a Lincoln man", his arrival in photography is topical in the serendipity of the careers of the great photographers of the 19th century. Sometimes an adventurer, sometimes a scientist, he was above all looking for an activity to exercise. On this subject, Jackson writes: “The basic purpose was always exploration. I was seldom more than an sideshow in a great circus.”

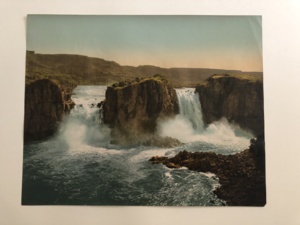

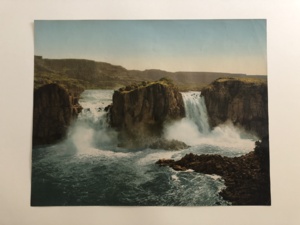

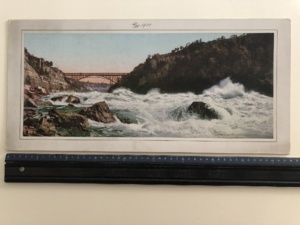

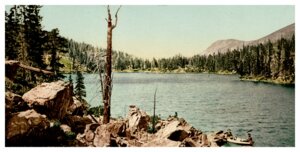

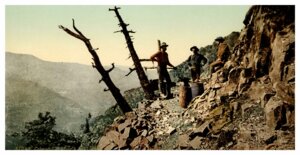

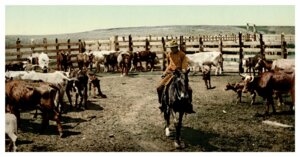

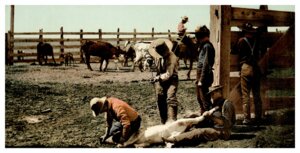

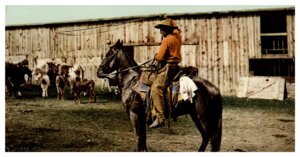

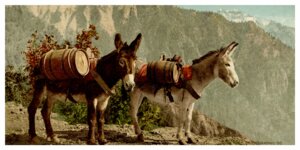

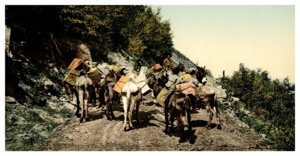

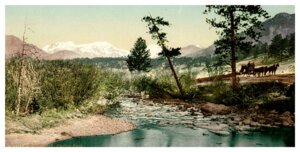

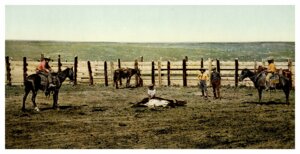

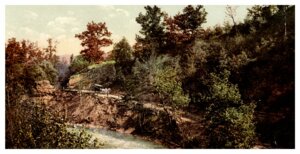

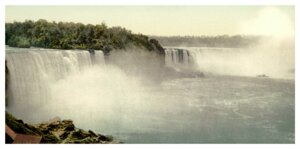

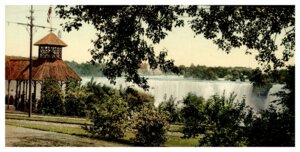

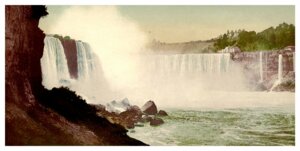

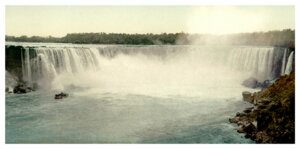

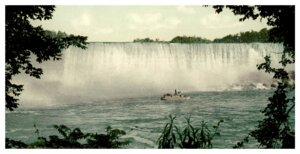

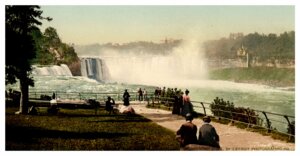

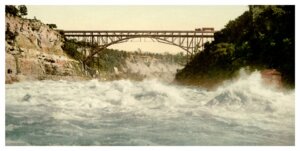

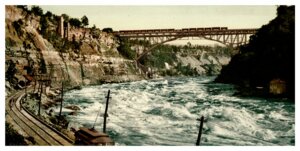

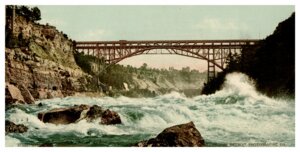

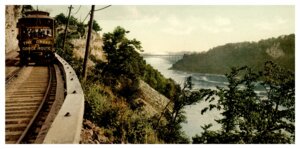

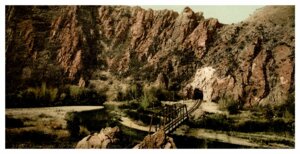

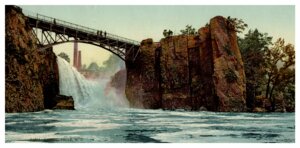

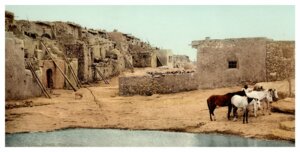

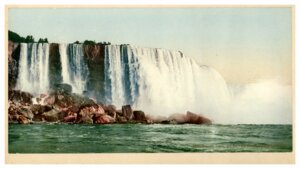

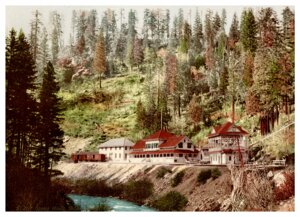

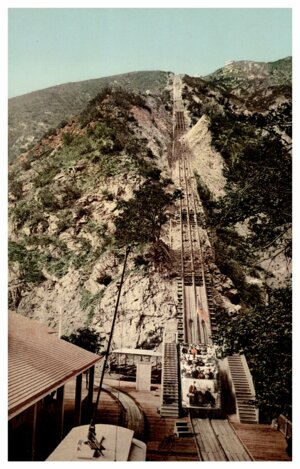

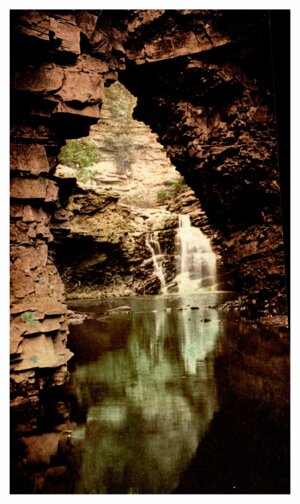

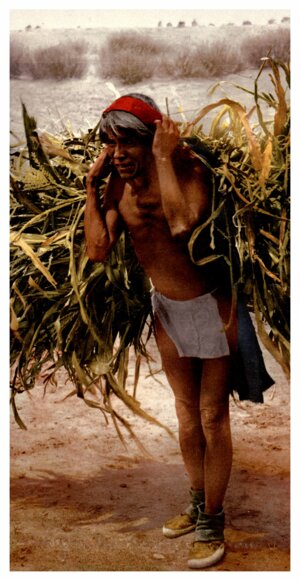

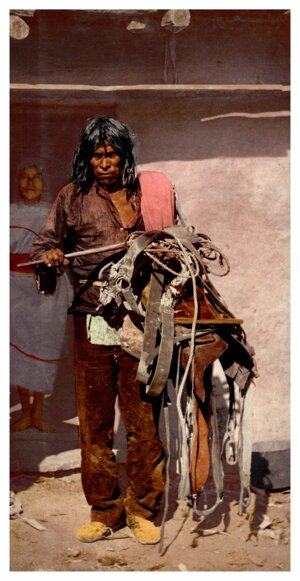

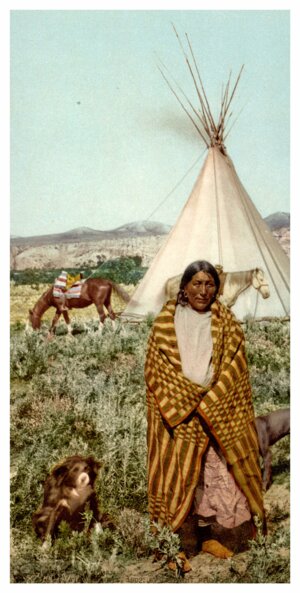

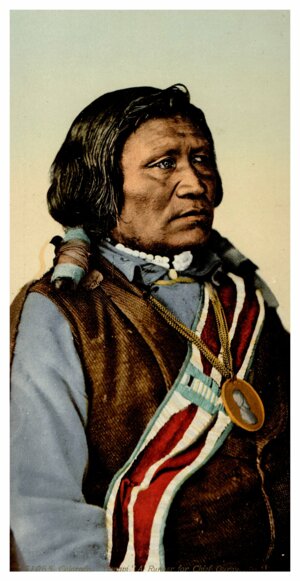

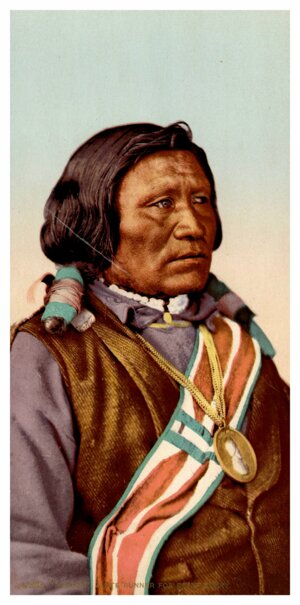

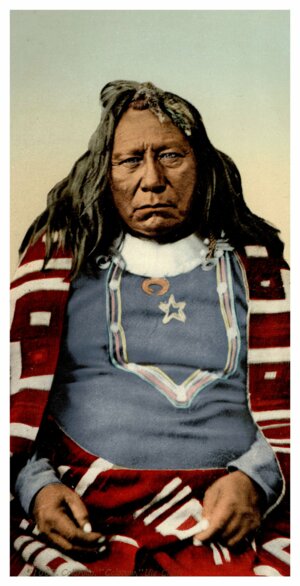

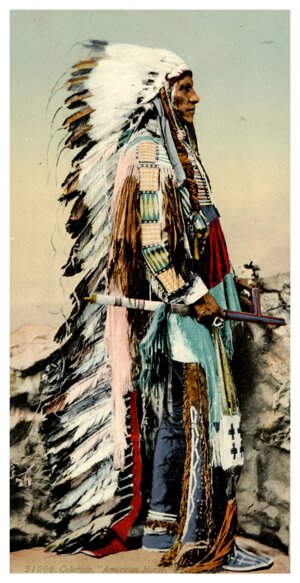

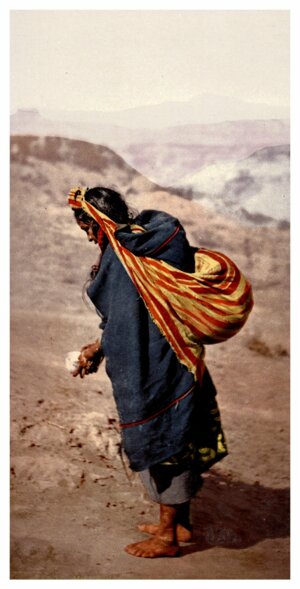

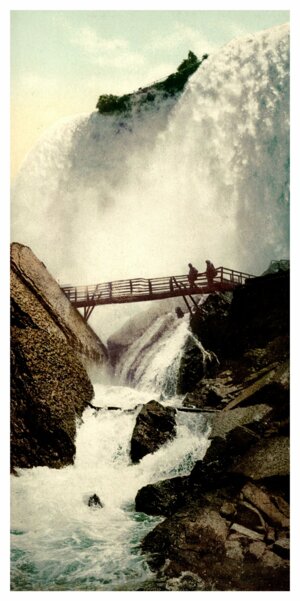

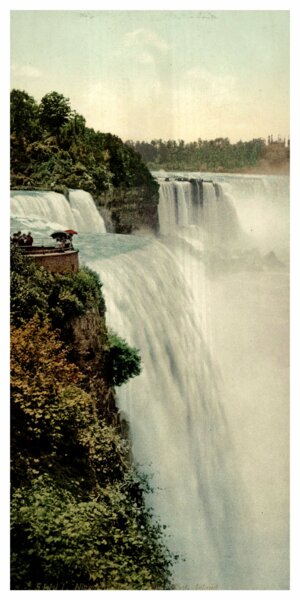

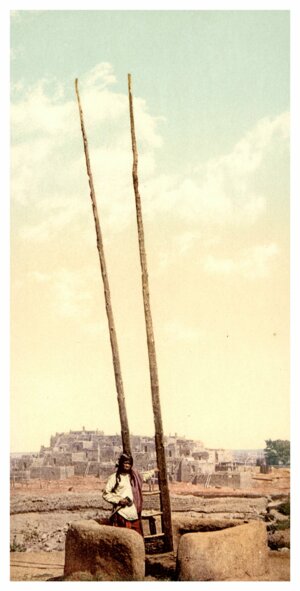

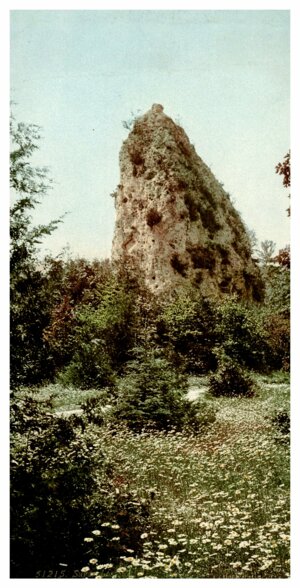

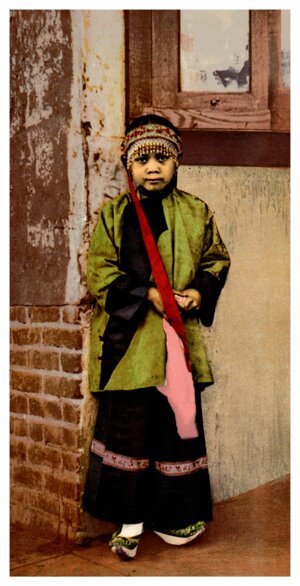

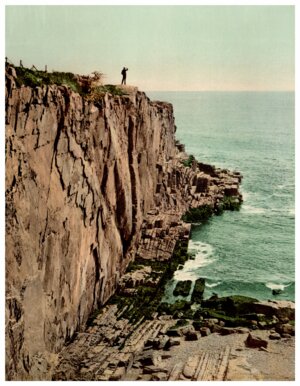

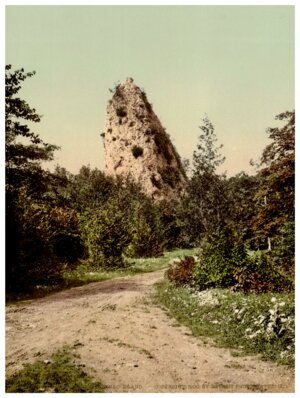

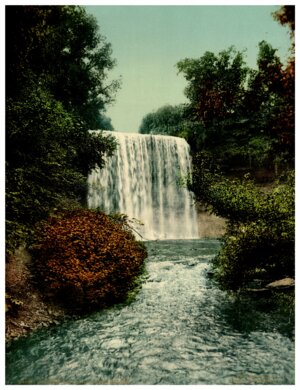

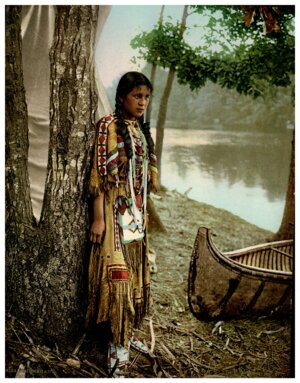

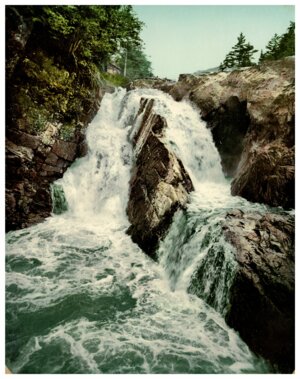

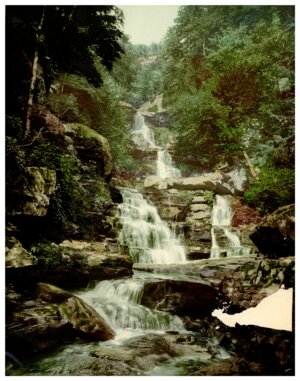

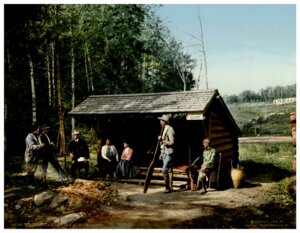

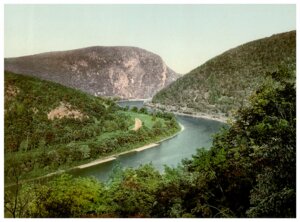

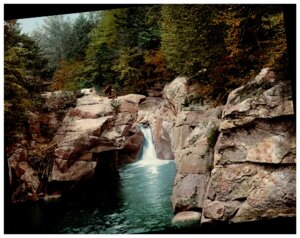

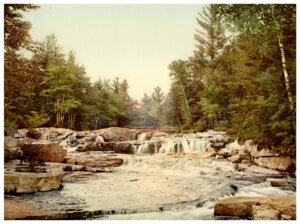

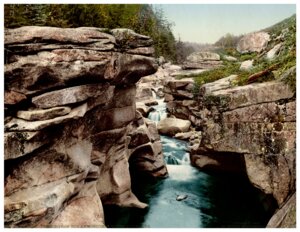

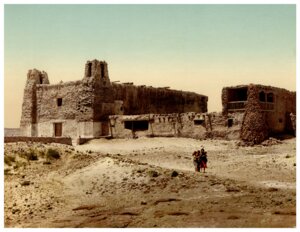

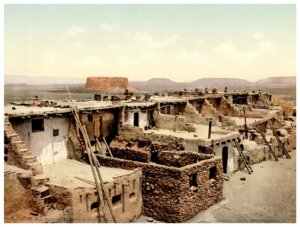

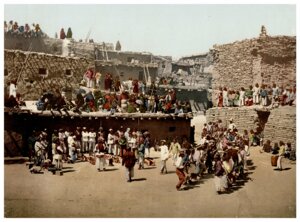

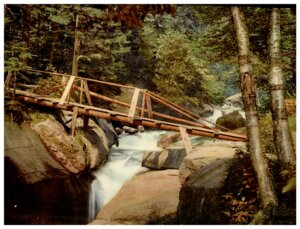

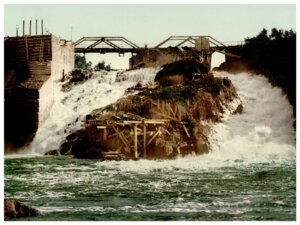

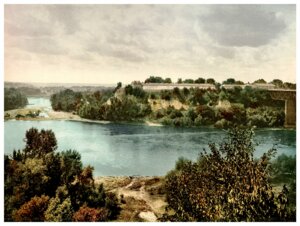

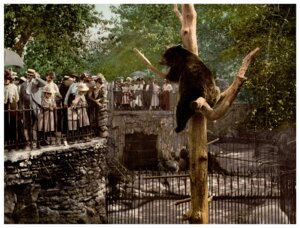

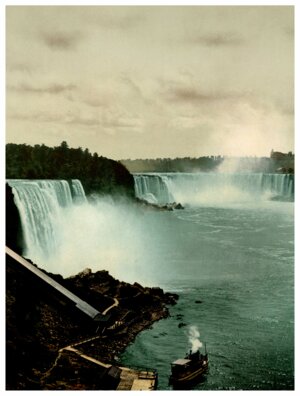

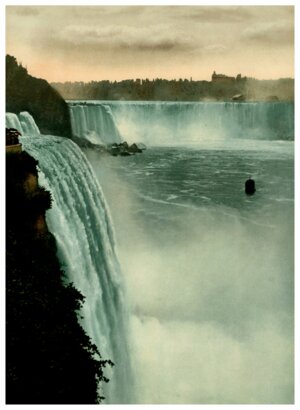

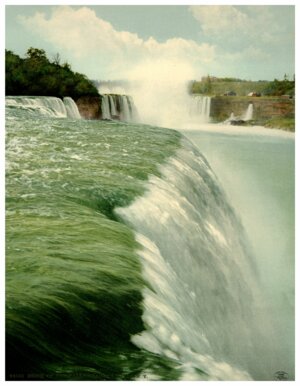

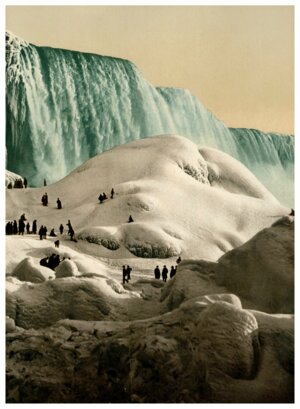

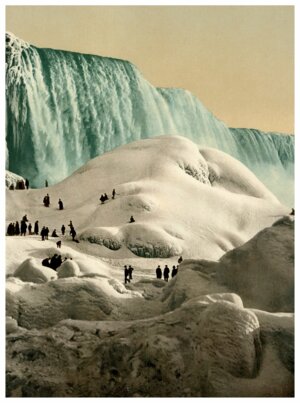

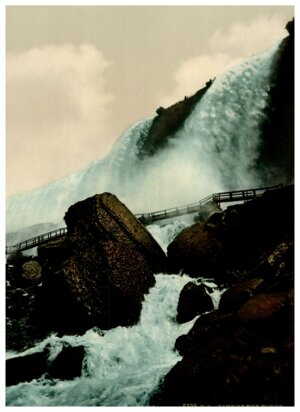

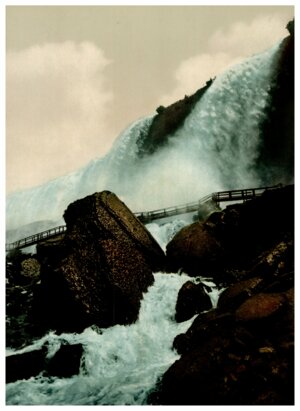

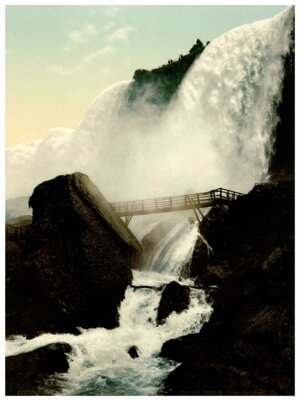

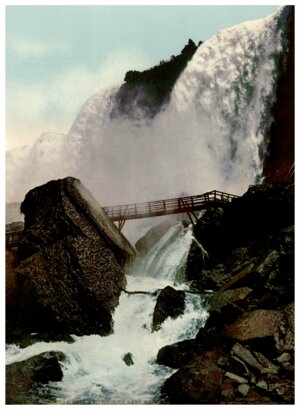

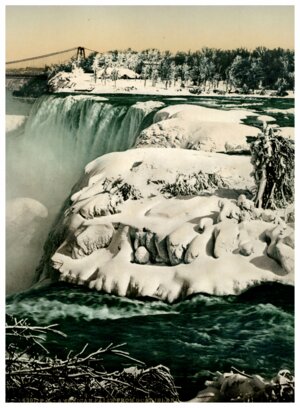

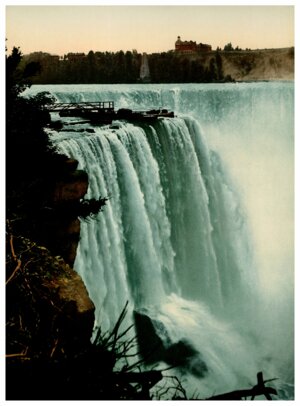

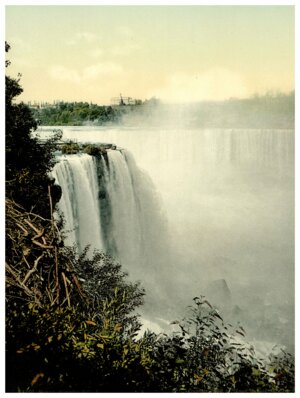

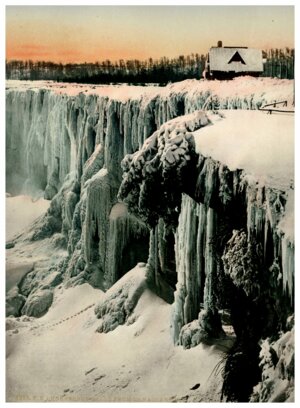

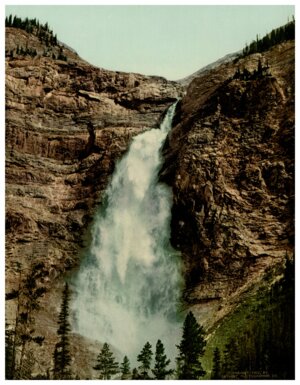

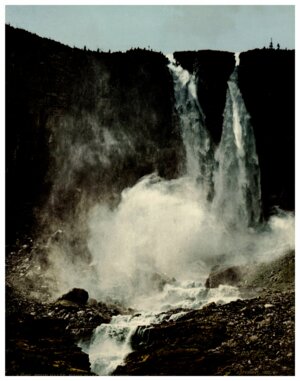

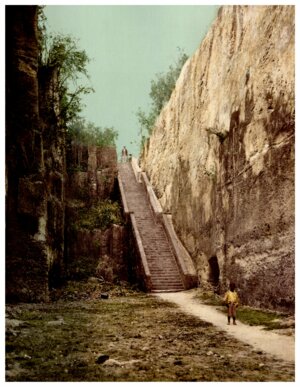

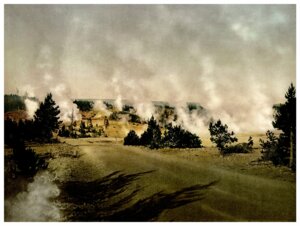

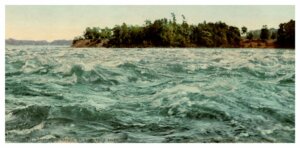

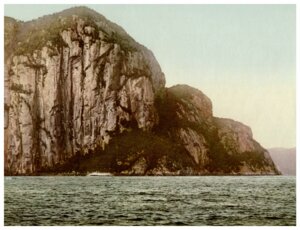

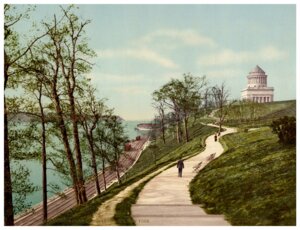

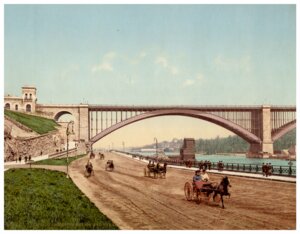

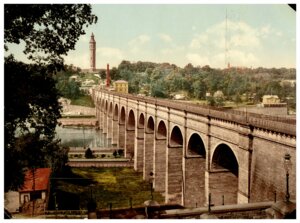

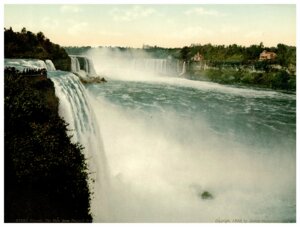

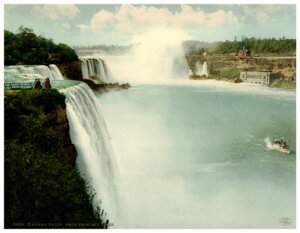

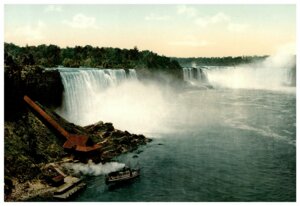

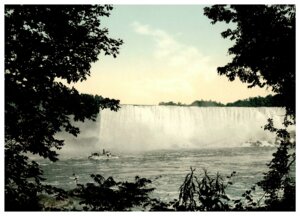

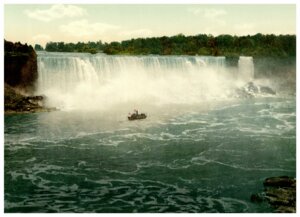

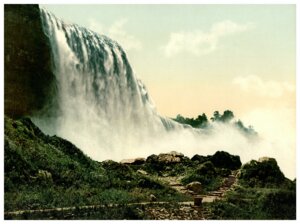

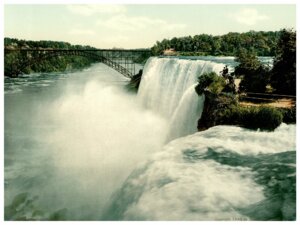

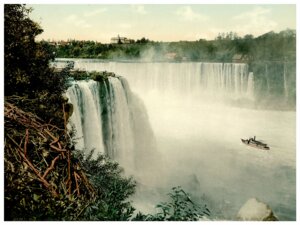

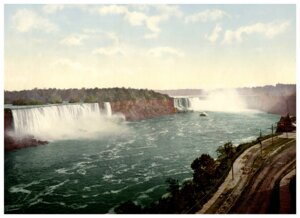

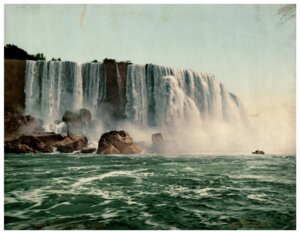

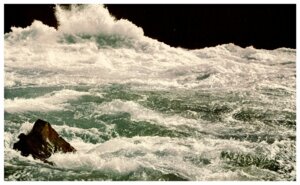

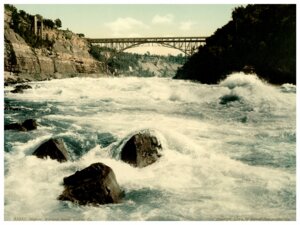

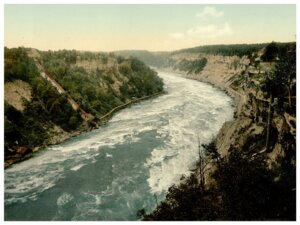

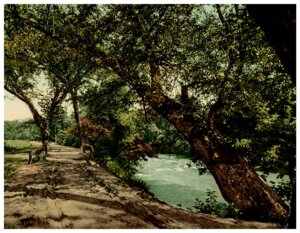

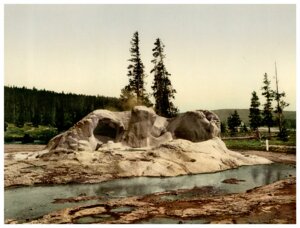

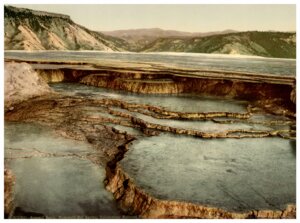

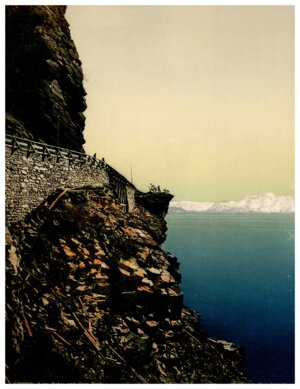

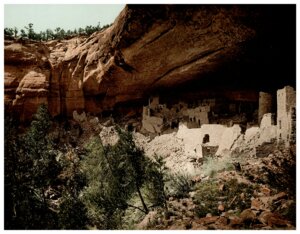

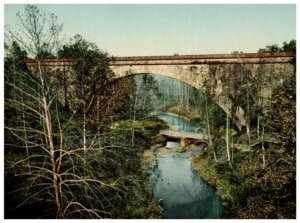

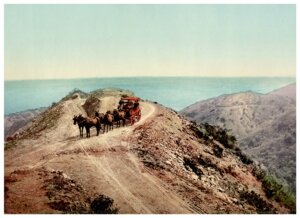

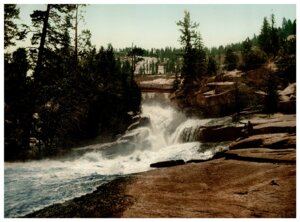

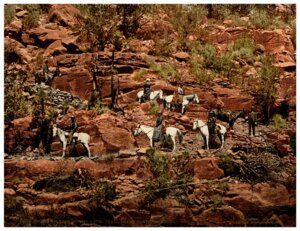

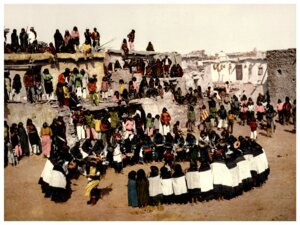

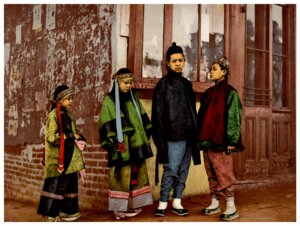

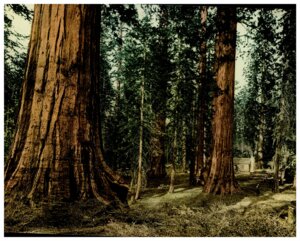

Friend and assistant of photographer Edric Eaton Hamilton, Jackson lived with him in the mid-1860s before buying his studio. During his many wanderings, he moves voluminous photographic equipment in steep places. In particular, he produced some 400 views of the "mythical" site of Yellowstone (according to his own term) where he immortalized the Mammoth Hot Springs. He also went to Niagara Falls. However, landscapes are not the only object of his interest. Like other photographers in the company, he was interested in the Native Americans, in particular their clothing or their hunting techniques. For this, he is helped by Doctor Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (1829-1887), geologist, who offers him to carry out studies and surveys on their way of life. The photographs of the DPC will also be of great help in convincing the American government to make Yellowstone a national park.

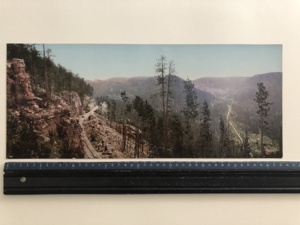

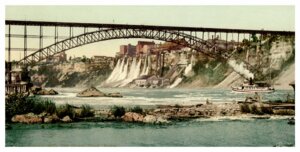

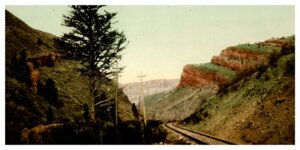

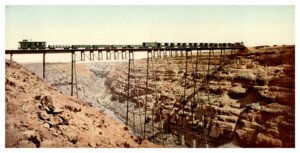

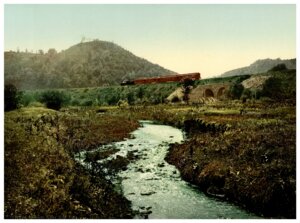

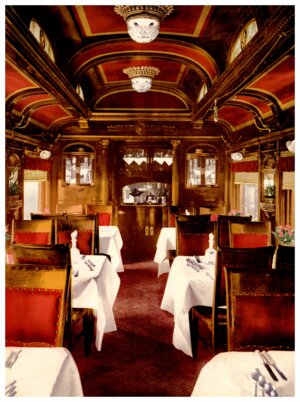

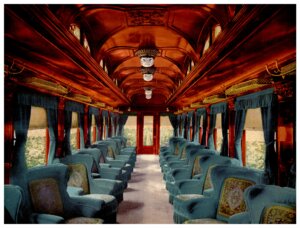

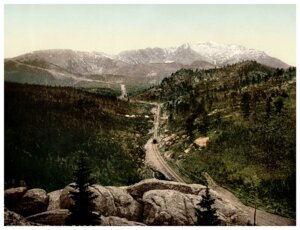

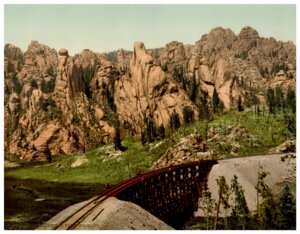

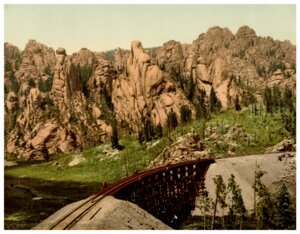

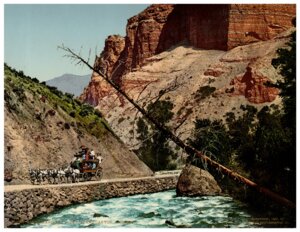

In 1902, Jackson traveled along the railway lines using a specially equipped railroad. For all that, the latter is not always at the center of his concerns. Also, Jackson could survey American territory without a clear idea of sight. He writes: “I had no special equipment. - I might get something. Who knows ? – was my attitude. ". Freely caustic and aware of his impetuous character, Jackson does not fail to be ironic about the men around him, in particular about the qualification of "naturalist" then conferred on any adventurer.

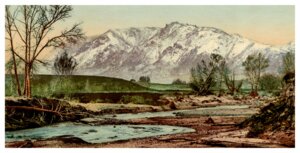

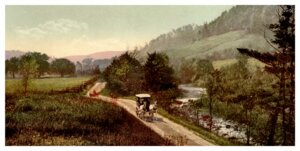

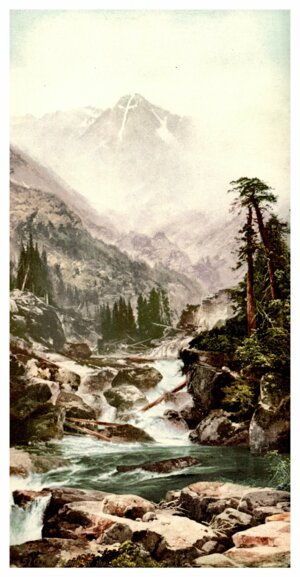

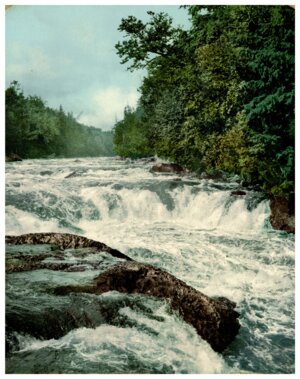

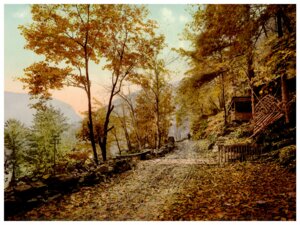

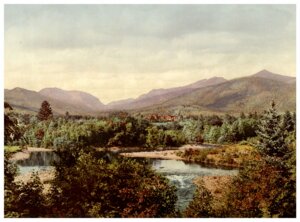

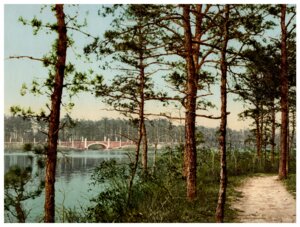

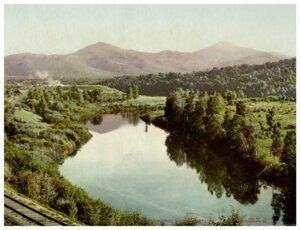

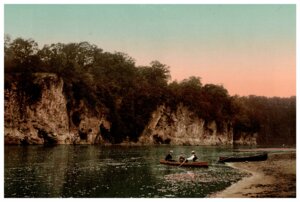

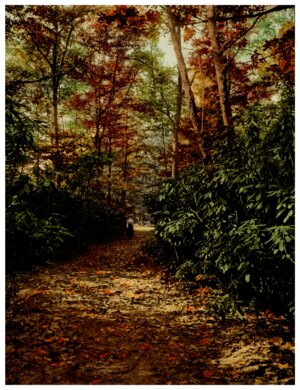

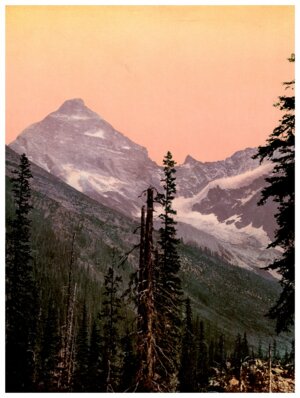

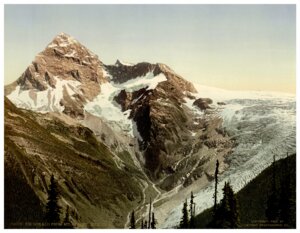

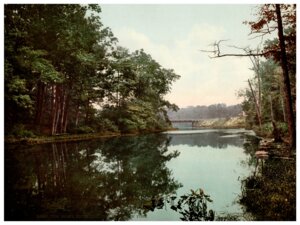

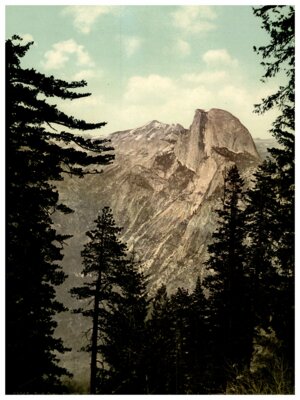

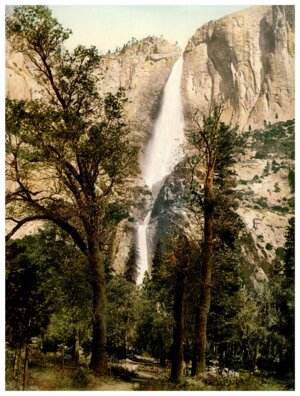

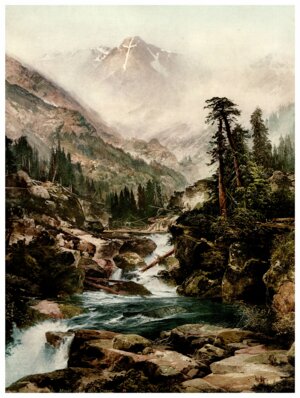

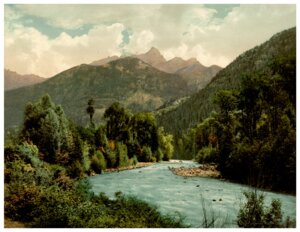

Regarding his photographic choices, the pictorial influence is great, especially on color. Jackson was deeply marked by the painting of Thomas Moran (1837-1926) with whom he undertook several expeditions, notably to Yellowstone in 1871. The work of the painter enabled him to better stage his plans. During the period 1868-1897, the improvement of the aesthetic choices in his photographs compared to some of his early sketches is edifying. This is particularly noticeable when it comes to framing and controlling depth of field. Jackson will end up influencing Moran himself and will never give up drawing because It allows him to overcome the deficiencies of photography in the reproduction of certain details.

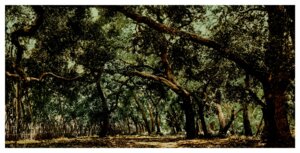

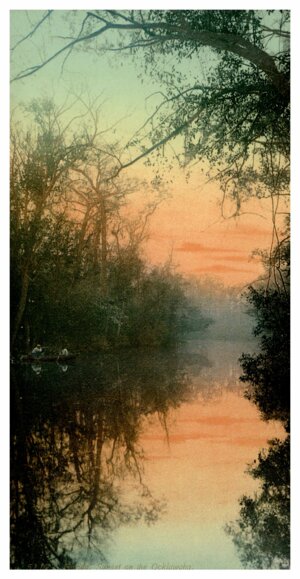

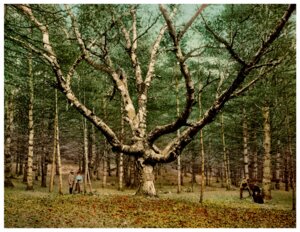

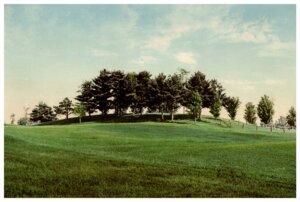

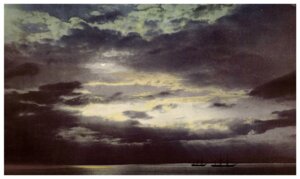

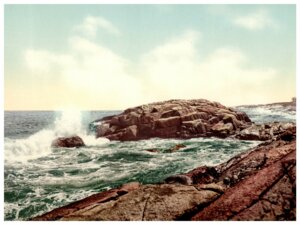

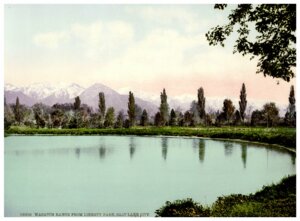

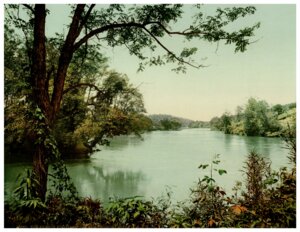

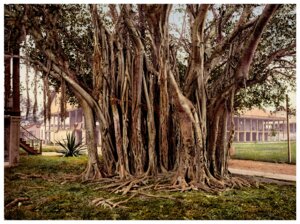

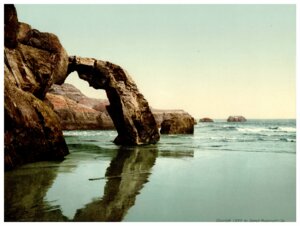

AN IDEALIZED NATURE?

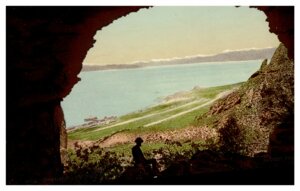

“While only a select few can appreciate the discoveries of the geologists or the exact measurements of the topographers, everyone can understand a picture.”

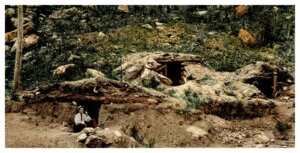

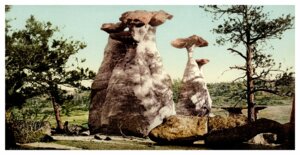

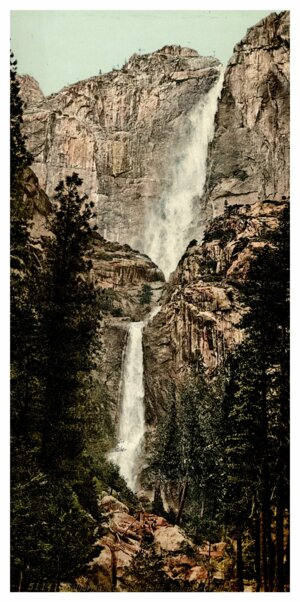

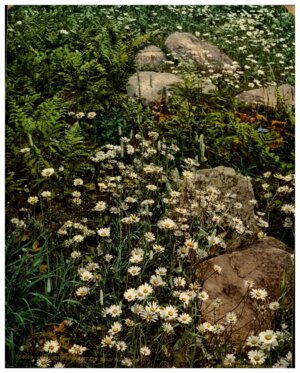

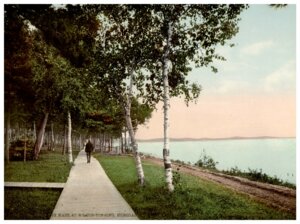

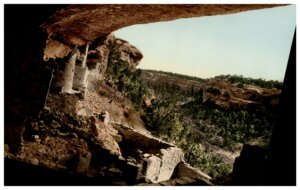

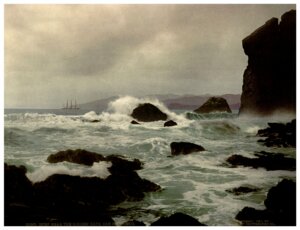

This quote from the New York Times of April 27, 1875 illustrates the power of photography which served, according to the formula of Gisèle Freund (1908-2000), to see up close what could only be approached from afar. Finally, if these images of great beauty have allowed some scientific progress, Jackson notably discovering Indian dwellings in the Southwest, they are also of great beauty. This aesthetic is that of nature, certainly sometimes idealized, just as much as a composition thought up by the photographer.

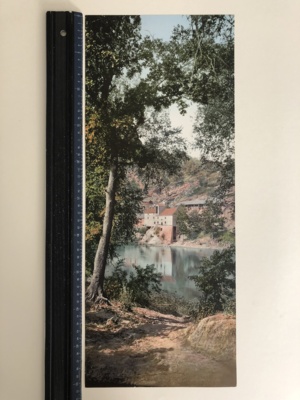

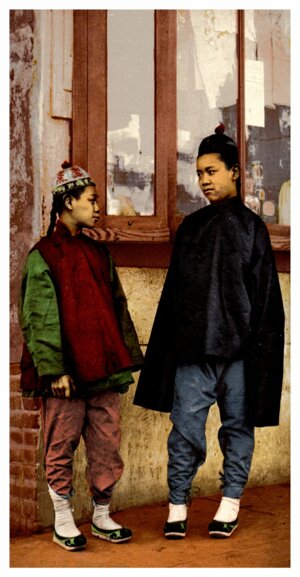

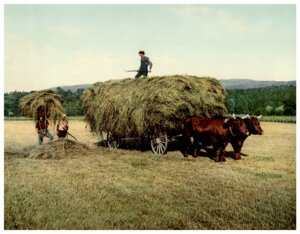

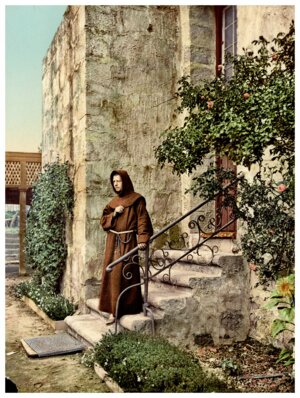

In line with Peter Henry Emerson (1856-1936), the photographers of the Detroit Photographic Company are nevertheless qualified as realists in that they oppose the melodramatic and artificial character of certain sleepy pictorialist views (costuming, staging…). Their goal is therefore to being true to nature by including an artistic dimension. This “uncompromising lens” as Jackson calls it is therefore part of the American tradition of “straight photography” as much as it is a way for the photographer to express his personal sensibility.

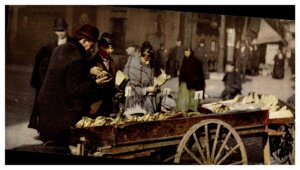

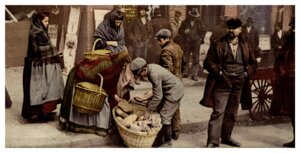

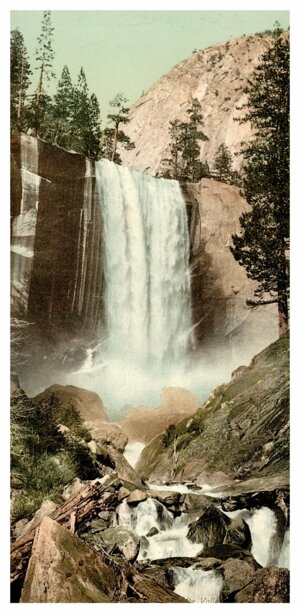

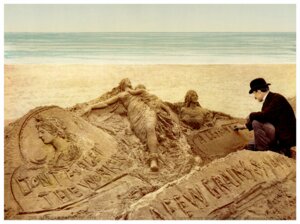

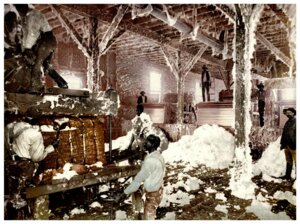

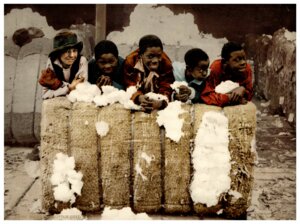

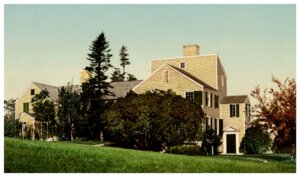

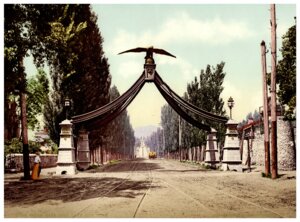

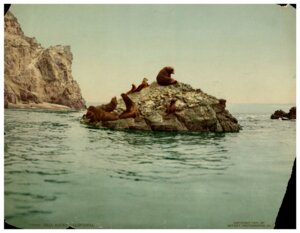

Beyond aesthetic choices, this form of idealization is an effective way to circumvent material difficulties. The DPC photographers will use retouching on many occasions, in particular the application of paint on the photograph. In theory, these touch-ups are added to enhance the image or remove obstructions such as utility poles. However, they also saved money by avoiding having to re-create views of the same site and achieve a more salable image. In order to modernize the prints, the dresses could for example be lengthened in order to correspond to the evolutions of fashion or the buildings constructed in the meantime added.

Thus, by their quality and their wide distribution, these photochromes constitute a real revolution in that they showed America the very look of the land. Indirectly, it also constitutes the first encounter of ancient Europeans with the rosy picture of the Native Americans the government then wishes to spread.

Bibliographie :

COKE Van Deren, The Painter and the Photograph, University of New Mexico Press, 1972, 324p.

HALES Peter, William Henry Jackson and the Transformation of the American Landscape, Temple University Press, 2011, 368p.

JACKSON William Henry, Time Exposure, Putnam, 1940, 342p.

JACKSON William Henry, Catalogue of the photographs of the U.S. geological and geographical survey of the territories, Washington printing office, 1875, 51p.

NEWHALL Beaumont, EDKINS Diana, William H.Jackson, Morgan & Morgan, 1974, 158p.

WALTER Walter, ARQUÉ Sabine, America 1900, Taschen, Basic Art Series, 2020, 612p.

INTRODUCTION

Pendant près de 30 ans, la Detroit Publishing Company fut l'un des principaux éditeurs d'images dans le monde. Entre 1895 et 1924, elle a en effet édité des portraits, des paysages ou des vues de villes, essentiellement aux Etats-Unis. Sont photographiés de grands centres urbains avec San Francisco, New York, Cleveland, Philadelphie ou Detroit, des lieux de loisirs avec les plages de Californie, de Floride ou d’Atlantic City ou encore la diversité de la végétation américaine. Cette dernière forme souvent composition avec des éléments de la modernité : chemins de fer, usines ou navires. Aussi, les photographes immortalisent les monuments de Washington, les paysages grandioses du Colorado ou des villes plus rurales comme Williamsburg. Enfin, des voyages seront l’occasion de réaliser des vues de pays limitrophes comme le Mexique, Cuba ou le Canada. Cette collection de plus de 1150 images constitue une fraction représentative de la diversité des productions de la compagnie.

HISTORIQUE

En 1895, William A. Livingstone s’associe avec Edwin H. Husher pour créer la Detroit Publishing Company dans le Michigan. Cette société était divisée en deux activités principales : d’une part la Photographic Company centrée sur la production de photographies et d’autre part la Photochrom Company qui s’occupait des tirages couleur. C’est ce procédé, acheté à la Photoglob Company de Zurich, qui fera leur succès. En effet, il sera décliné sous la forme de cartes postales, de photos sépia ou de lantern slides. Le procédé consiste en une forme de photolithographie qui nécessitait 16 couleurs pour produire l’image finale. L’ensemble du processus de création des photochromes n’est pas encore connu et des recherches se poursuivent depuis les années 1990 pour en reconstruire le cheminement. Quoi qu’il en soit, si ce dernier permet à la compagnie d’écouler jusqu’à 7 millions de tirages par an, il sera également à l’origine de sa chute. Avec l’apparition de techniques simplificatrices et sa qualification d’activité non-essentielle à l’effort de guerre par le gouvernement, la société est finalement placée en redressement judiciaire en 1924.

LES PHOTOCHROMES

En ce qui concerne leurs caractéristiques matérielles, les photochromes, principalement réalisés entre 1897 et 1914, sont légèrement brillants. Ils peuvent être montés sur carton, et, bien souvent, comportent une légende en lettres dorées placée sous l’image qui permet d’identifier la vue, voire le photographe. Au sommet de sa gloire, la compagnie disposait d’un fonds d’environ 40.000 négatifs très divers incluant des vues de ville, de paysages, d’évènements ou de loisirs. Ces vues étaient aussi employées à des fins publicitaires ou vendues à des musées, des bibliothèques et des écoles. Lorsqu’elle souhaitait produire un nouveau photochrome, c’est dans ce vivier de photographies noir et blanc que puisait la DPC. De fait, fréquemment, des indications quant aux choix de couleur se trouvent au dos des photographies noir et blanc. En ce qui concerne leur taille, les grands formats colorés peuvent mesurer jusqu’à 55 cm de long et jusqu’à 65 cm de long pour les panoramas comme celui de Cripple Creak au Colorodo également conservé à la Library of Congress de Washington. Cet emploi de grands formats permet de mieux retranscrire l’immensité de l’espace à celui qui contemple la photographie.

WILLIAM H. JACKSON (1843-1942)

Plusieurs photographes ont travaillé avec la compagnie comme Henry Greenwood Peabody, Lycurgus S. Glover, Edward H. Hart ou John S. Johnson.

Néanmoins, la pierre angulaire de ce succès était le photographe William Henry Jackson. Ce dernier rejoint l’aventure à la fin 1897 et réalisera 10.000 plaques de verre pour enrichir le fonds de la compagnie. Il ne se contente par ailleurs pas de réaliser des tirages lui-même mais rachète également les fonds des photographes qu’il rencontre lors de ses voyages aux Etats-Unis, au Canada ou dans les Caraïbes.

Jackson est le premier à réaliser des tirages couleur du Grand Canyon, découvert en 1850. Ceci lui vaut un succès personnel qui rejaillit sur la compagnie. Par ailleurs, son autobiographie intitulée Time Exposure est riche d’enseignements sur le fonctionnement de la DPC et sur sa formation esthétique. Publiée en 1940, il y raconte longuement son passé militaire et sa passion pour la peinture de paysage. Il ressort de ce récit que Jackson usait en permanence de son carnet à dessin ce qui a permis un développement précoce de son talent pour l'instantané.

Se définissant comme « a Lincoln man », sa venue dans la photographie est topique de la sérendipité du parcours des grands photographes du XIXème siècle. Tantôt aventurier, tantôt scientifique, il cherchait avant tout une activité à exercer. A ce sujet, Jackson écrit : « L’objectif principal était toujours l’exploration. J’étais rarement davantage qu’une attraction dans un grand cirque. »

Ami et assistant du photographe Edric Eaton Hamilton, Jackson vit avec lui au milieu des années 1860 avant de racheter son studio. Lors de ses très nombreuses pérégrinations, il déplace un matériel photographique volumineux dans des lieux parfois escarpés. Il réalise notamment quelque 400 vues du « mythique » site de Yellowstone (selon son propre terme) où il immortalise les Mammoth Hot Springs et se rend également aux chutes du Niagara. Les paysages ne sont cependant pas seuls l’objet de son intérêt. Comme d’autres photographes de la compagnie, il s’intéresse aux Indiens, en particulier à leurs tenues vestimentaires ou à leurs méthodes de chasse. Pour cela, il est aidé du Docteur Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (1829-1887), géologue, qui lui propose de réaliser études et enquêtes sur leur mode de vie. Les photographies de la DPC seront par ailleurs d’une grande aide afin de convaincre le gouvernement américain de faire de Yellowstone un parc national. En 1902, Jackson se déplace en suivant les lignes de chemin de fer à l’aide d’un wagon aménagé en studio photographique. Bien que le matériel qu’il emploie soit imposant, ce dernier n’est pas toujours au centre de ses préoccupations. Aussi, Jackson pouvait arpenter le territoire américain sans idée précise de vue. Il écrit : « Parfois, je n’avais pas d’équipement spécial. - Je pourrais obtenir quelque chose. Qui sait ? – était ma conduite. ». Volontiers caustique et conscient de son caractère impétueux, Jackson ne manque pas d’ironiser sur les hommes qui l’entourent, en particulier sur la qualification de « naturaliste » alors conférée à n'importe quel aventurier.

En ce qui concerne ses choix photographiques, l’influence picturale y est grande, en particulier sur la couleur. Jackson est profondément marqué par la peinture de Thomas Moran (1837-1926) avec lequel il entreprend plusieurs expéditions, notamment à Yellowstone en 1871. Le travail du peintre lui a par exemple permis de mieux étager ses plans. Pendant la période 1868-1897, l’amélioration des choix esthétiques dans ses photographies par rapport à certaines de ses esquisses est édifiante. Ceci est particulièrement visible en ce qui concerne le cadrage, la clarté de l’image et la maîtrise de la profondeur de champ. Jackson finira par influencer lui-même Moran et n'abandonnera jamais le dessin car ce dernier lui permet de pallier les carences de la photographie quant à la reproduction de certains détails.

UNE NATURE IDÉALISÉE ?

« Alors que seuls quelques privilégiés peuvent apprécier les découvertes des géologues ou les mesures exactes des topographes, chacun peut comprendre une image. »

Cette citation du New York Times du 27 avril 1875 illustre la puissance de la photographie qui servait, selon la formule de Gisèle Freund (1908-2000), à voir de près ce qu’on ne pouvait approcher que de loin. Enfin, si ces images d’une grande beauté ont permis quelques progrès scientifiques, Jackson découvrant notamment des habitations indiennes dans le Sud-Ouest, elles sont également d’une grande beauté. Cette esthétique est celle de la nature, certes parfois idéalisée, tout autant qu’une composition pensée par le photographe.

S’inscrivant dans la lignée de Peter Henry Emerson (1856-1936), les photographes de la Detroit Photographic Company sont pourtant qualifiés de réalistes en ce qu’ils s’opposent au caractère mélodramatique et artificiel de certaines vues pictorialistes ensommeillées (costumes, jeu d’acteur…). Leur but est donc de demeurer fidèle à la nature en y incluant une dimension artistique. Cette « uncompromising lens » telle que la nomme Jackson s’inscrit donc dans la tradition américaine de la « straight photography » tout autant qu’elle est un moyen pour le photographe d’exprimer sa sensibilité personnelle.

Au-delà de choix esthétiques, cette forme d’idéalisation constitue un moyen efficace pour contourner des difficultés matérielles. Les photographes de la DPC vont user à de nombreuses reprises de retouches, en particulier l’application de peinture sur la photographie. En théorie, ces retouches sont ajoutées pour rehausser l’image ou retirer ce qui peut gêner la vue comme les lignes téléphoniques. Cependant, elles permettaient également des économies en évitant de devoir réaliser à nouveau des vues du même site. Afin de moderniser les tirages, les robes pouvaient par exemple être allongées afin de correspondre aux évolutions de la mode ou les bâtiments construits entre temps ajoutés.

Ainsi, par leur qualité et leur large diffusion ces photochromes constituent une véritable révolution en ce qu’ils ont montré à l’Amérique la véritable apparence des terres du pays. Indirectement, ils constituent la première rencontre des anciens Européens avec l’image d’Epinal de l’Indien que le gouvernement souhaite alors diffuser.

Price on request